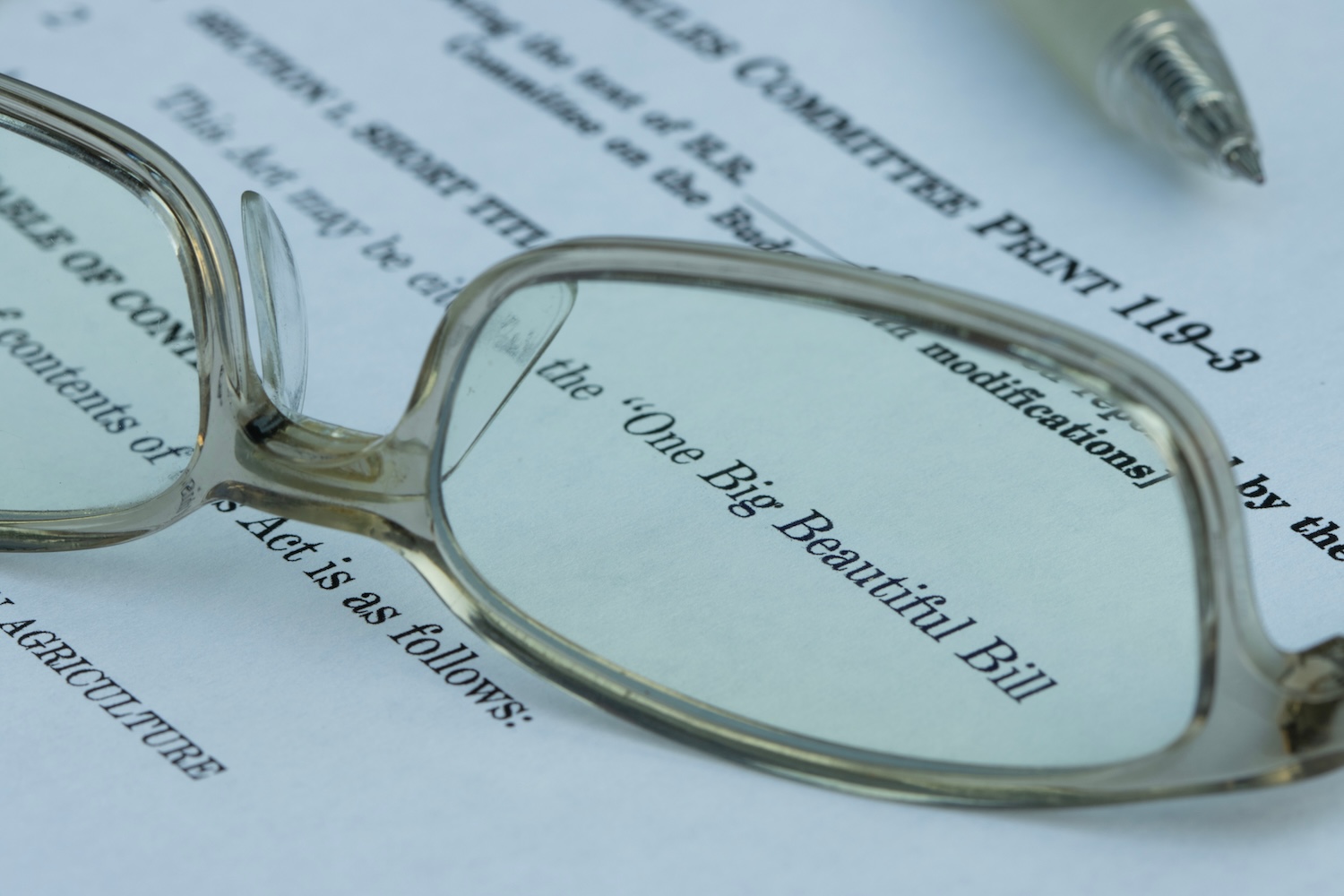

On July 4, 2025, President Donald Trump signed into law H.R. 1, the so-called “One Big Beautiful Bill.” Congress passed the bill through a budgetary process called “reconciliation,” which allows members of Congress to bypass the normal rules in the Senate that require at least 60 votes to pass legislation. As a result, only a simple majority vote is needed in both chambers.

In recent years, this process has been used when one party controls both Congress and the presidency as it does not require votes from members of the minority party. However, all provisions in a reconciliation bill must relate to the federal budget, funding, or debt-limit. As a result, reconciliation is a tool for the majority party to advance federal funding needs based on its policy agenda.

On July 1, 2025, the Senate passed H.R. 1 by a 51-50 vote with three Republican senators joining all Democrats and Independent senators to vote against the bill. Vice President J.D. Vance issued the tie-breaking vote. Two days later, the House of Representatives passed the bill without changes by a 218-214 vote, with all Democrats voting against it and joined by two Republicans.

The final bill includes significant immigration- and border-related spending measures that pour billions of dollars into immigration and border enforcement and impose many mandatory and cost-prohibitive fees on certain immigration benefits applications. H.R. 1 includes other non-spending measures affecting noncitizens, including restricting their eligibility for certain public benefits or tax programs. This analysis excludes those provisions.

Immigration and Border-Related Spending Provisions

Overview of Spending

H.R. 1 provides $170.7 billion in additional funding for immigration- and border enforcement-related activities to the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) and its sub-agencies, Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) and Customs and Border Protection (CBP) as well as for the Department of Defense (DOD) for activities related to the military’s presence along parts of the southern border.

H.R. 1 implicitly drives dramatic changes to immigration policy through the spending of federal tax dollars. Because these funds are provided through reconciliation—and not the regular appropriations process—they do not include directives about how the funds must be used, which prevents members of Congress from conducting meaningful oversight. Importantly, these funds all need to be spent by September 30, 2029 but the agencies receiving them have significant discretion as to how to allocate them across the next 51 months.

| Spending Category | Funding Amount |

|---|---|

| Construction and maintenance of border wall, CBP checkpoints, and CBP facilities | $51.6 billion |

| Border Patrol agents and vehicles, and Federal Law Enforcement Training Center improvements. | $7.8 billion |

| Border technology and vetting | $6.2 billion |

| Operation Stonegarden (funding to state and local law enforcement agencies to support border enforcement) | $450 million |

| Border processing, including for unaccompanied children, Remain in Mexico, and expedited removal | $2.1 billion |

| Prosecutions of noncitizens, compensating local governments for incarcerating noncitizens, combatting drug trafficking, immigration judges | $3.3 billion |

| Detention capacity expansion | $45 billion |

| Enforcement and removal, including hiring ICE agents, transportation costs, and detaining families | $29.9 billion |

| State immigration and border enforcement cost-reimbursement funds | $13.5 billion |

| DHS cost-reimbursement fund for border enforcement | $10.0 billion |

| DOD support for immigration and border enforcement | $1.0 billion |

| Total | $170.7 billion |

Legal Immigration and Relief from Removal

H.R. 1 turns immigration into a pay-to-play system by significantly increasing fees on benefit requests like asylum applications and Temporary Protected Status (TPS) and on applications seeking relief from removal by individuals facing deportation in immigration court. Procedural and time-sensitive requests also see fee hikes, including motions in immigration courts to reopen a case and appeals of an immigration judge’s decision. In addition, those seeking to come to the United States are also impacted with a new $250 “visa bond” for all nonimmigrant visas, which could be reimbursed only after the visa expires and the visa holder proves they had a record of perfect compliance.

These fees, many of which are authorized to be layered on top of existing fees, are largely mandatory, effectively putting legal pathways out of reach for thousands of people. For example, for the first time asylum applicants must not only pay a fee to apply for asylum—set at $100—but an additional $100 fee every year the application is pending adjudication. An asylum seeker who requests at least one work permit and waits 5 years to obtain a decision on their asylum claim in the heavily backlogged immigration system is estimated to pay at least $1,150 in filing fees under H.R. 1 compared to $0 before the bill’s enactment.

The new fees place the burden of the backlogged immigration system on the applicants themselves. By making many mandatory and embedding fee increases through the application process, the steep fees effectively block access to those unable to afford them. See Table 1 for more details on fee changes.

Detention

H.R. 1 provides $45 billion for building new immigration detention centers, including family detention facilities. When averaged out over the next 51 months, this constitutes an additional $10.6 billion for detention per year through Fiscal Year 2029, bringing ICE’s total detention budget to a minimum of $14 billion per year. This amount represents a 308 percent increase on an annual basis over ICE’s FY 2024 detention budget. By comparison, the entire Federal Bureau of Prison’s budget was $8.6 billion in FY 2025. The overwhelming majority of the funding for ICE detention will likely go to private companies contracted to build and run detention facilities.

Based on an estimate of detention costs that ICE provided to Congress in January 2025, we estimate that an additional $10.6 billion per year could likely fund an increase in ICE detention to at least 116,000 beds, with $6 billion per year spent on contracting with existing detention centers and $8 billion per year spent on building and operating new “soft-sided” detention camps consisting primarily of tents and trailers.

However, because ICE is not required to spend this money evenly across the next 51 months, ICE could ultimately reach a higher detention population by September 30, 2029. H.R. 1 also provides $3.5 billion for state and local cooperation with ICE, which could lead to states constructing their own “soft-sided” detention centers and leasing them to ICE, as Florida has already done. Therefore, the bill could lead to an increase in ICE detention to 125,000 beds or higher—just below the current population of the entire federal prison system.

In addition to authorizing more detention, H.R. 1 uses tax dollars to dismantle core legal protections for children by implicitly overriding provisions in the Flores settlement agreement that limit the time minors can be detained. Whether this language overrules the Flores settlement is still to be decided by courts.

H.R. 1 also authorizes the DHS Secretary to set minimal detention standards for single adult detention facilities without having to go through normal review, creating a situation where private prison operators whose facilities fail to meet current standards could be granted contracts anyway. The consequences of providing such large sums of money to increase detention without commensurate oversight will exacerbate deleterious and inhumane conditions that have been endemic to the detention system for years, including medical neglect, overcrowding, overuse of solitary confinement, and preventable deaths.

Arrests

H.R. 1 provides a single lump sum of $29.9 billion toward ICE’s enforcement and deportation operations, including funding to hire an additional 10,000 ICE officers in five years, modernize its fleet and other deportation-related transportation costs, and hiring new ICE attorneys to represent the government in immigration court. Because this funding is provided as a lump sum with a list of allowable expenses, H.R. 1 gives ICE significant flexibility in how it uses and allocates this money toward immigration enforcement.

With this funding, the current administration will be poised to dramatically expand community arrests and expand cooperation with state and local law enforcement agencies. Given the recent dismantling of three primary DHS oversight agencies, this funding rapidly expands ICE’s enforcement capacity at a time when the agency has failed to provide timely and accurate information on the whereabouts of those it has arrested.

The $3.5 billion fund for states to assist in immigration enforcement could also be used to increase state and local law enforcement’s cooperation with ICE’s arrest operations, leading to an increase in immigration enforcement.

Immigration Court

H.R. 1 includes funding for the Executive Office for Immigration Review (EOIR)—which oversees the country’s immigration court system—as an allowable expense under a lump sum of $3.3 billion to the Department of Justice (DOJ). It also limits the number of immigration judges to 800 starting on November 1, 2028. Given this limitation and that EOIR currently has about 700 immigration judges, only a portion of total is likely to be allocated to EOIR.

By providing only a relatively small additional sum to the immigration courts while significantly increasing funding for immigration arrests and detention, H.R. 1 will dramatically increase already high immigration court case backlogs particularly for people held in detention facilities. The bill’s cap on the number of immigration judges at 800 will severely restrict progress on backlog reduction. Immigrants held in detention could be forced to wait months between every hearing while immigrants proceeding in their cases outside of detention would face even longer wait times as judges were reassigned to detained dockets.

Children

While two initially proposed fees that required family members and other sponsors to pay thousands of dollars to sponsor unaccompanied children were ultimately removed from the final text of H.R. 1, a combination of new mandatory fees in the final bill will make it more challenging for children to make a case for permanent safety. For example, children will now have to pay a mandatory $100 to apply for asylum or a potentially waivable $250 to apply for Special Immigrant Juvenile Status.

In addition, H.R. 1 removes existing statutory protections regarding licensing of family residential centers, which places children at risk of prolonged detention in unsafe conditions.

The bill also contains a $300 million fund for the Office of Refugee Resettlement to conduct background checks and home studies on any potential sponsor of a child and to conduct physical examinations of the bodies of all children in ORR custody (regardless of age) to check for tattoos or other identifying marks.

Border

H.R. 1 funnels $46.6 billion into border wall construction—more than 3 times what the Trump administration spent in its first term despite the failure of the wall to improve or contribute in any meaningful way to a border management strategy. It also includes $5 billion for updating and constructing CBP facilities and checkpoints.

The bill also includes $7.8 billion for CBP to hire and retain 3,000 new Border Patrol agents, vehicles and new infrastructure for the Federal Law Enforcement Training Center. And it provides $450 million for Operation Stonegarden, a program that funds cooperation with state and local law enforcement at the border.

H.R. 1 includes $1 billion for the DOD to support the military’s border operations. This includesthe deployment of military personnel in support of border operations and the temporary detention of migrants.

State Grants for Immigration- and Border-Related Enforcement

H.R. 1 includes at least $14 billion for states to support border-related immigration enforcement. In addition to the $450 million for Operation Stonegarden, the bill provides $10 billion for a “State Border Security Reinforcement Fund” for constructing border barriers and apprehending migrants at the border. In addition, H.R. 1 includes $3.5 billion for reimbursements to state or local governments for costs related to immigration-related enforcement, detention, and criminal prosecutions.

These funding provisions for states and local governments cover actions taken on or after January 21, 2021. In practice, this means that a significant portion of these federal funds will likely reimburse Texas for its state-run immigration enforcement program known as Operation Lone Star. Texas has spent over $11 billion on the program thus far. While H.R. 1 will fund this large-scale state immigration enforcement effort, the Trump administration has simultaneously paused grants made to states and localities for programs responding to the urgent humanitarian needs of newly-arrived migrants and has proposed eliminating it completely in the next fiscal year.

Border Enforcement Fund

H.R. 1 establishes a new $10 billion fund to reimburse DHS for costs related to “safeguard[ing] the borders of the United States to protect against the illegal entry of persons or contraband.” This provision provides very few guardrails and little guidance to DHS on how to distribute these funds and by when. As a result, this is likely to become a slush fund for DHS to largely use however it determines. Compared to a single year, these funds represent nearly 50% of CBP’s FY 2024 budget.

TABLE 1: Fee Increases on Immigration Benefits

H.R. 1 creates new fees and dramatically increases others for certain immigration applications and forms of humanitarian protection. Below are five charts with a comparison of current and proposed fees across DHS, U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS), CBP, Department of State (DOS), and EOIR.

Importantly, all proposed fees are the minimum required, meaning they can be increased by the agency or department, and may be layered on top of existing fees. In addition, all fees are subject to yearly inflationary adjustments. Alarmingly, the proceeds of these fees largely go to the general fund at the Treasury Department and not for application processing.

There are many fees where fee waivers are now prohibited.

| USCIS Applications | What It Covers | Previous Fee | H.R. 1 Fee (FY 2025) | Fee Waiver or Exemption? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asylum Application Fee | Filing an I-589 asylum application under INA § 208 | $0 | $100 | No fee waiver |

| Pending Asylum Application Fee | Pending I-589 asylum application under INA § 208, must be paid every calendar year an application is pending. | $0 | $100/year | No fee waiver |

| Initial Work Permit Fee (Asylum Applicants) | Initial work permit for asylum applicants under (c)(8) | $0 | $550 | No fee waiver |

| Renewal Work Permit Fee (Asylum Applicant) | Renewal work permits for asylum applicants under (c)(8) | $520 (paper) or $470 (online) | $275 | No fee waiver |

| Temporary Protected Status (TPS) | Fee for registering for TPS | $50 | $500 | No fee waiver |

| Parole Fee (Humanitarian or Significant Public Interest) | Any noncitizen paroled into the U.S. (except under certain humanitarian situations) | $630 (paper) or $580 (online) | $1,000 | No fee waiver, but exception may apply based on the reason parole requested. |

| Initial Work Permit Fee (Parolees, TPS Holders) | Initial work permits for paroled noncitizens under (c)(11) and TPS applicants H.R. 1 limits work permits validity to up to 1 year. | $520 (paper) or $470 (online) | $550 | No fee waiver |

| Renewal Work Permit Fee (Parolees, TPS Holders) | Renewal work permits for paroled noncitizens under (c)(11) and those granted TPS H.R. 1 limits work permits validity to up to 1 year. | $520 (paper) or $470 (online) | $275 | No fee waiver |

| Special Immigrant Juvenile Status (SIJS) Fee | Fee for SIJS Petition (Form I-360) for children who are abandoned, abused, or neglected by one or both parents under INA § 101(a)(27)(J)) | $0 (exempt) | $250 | May request fee waiver |

| Department of State (DOS) Applications | What It Covers | Previous Fee | H.R. 1 Fee (FY 2025) | Fee Waiver or Exemption? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nonimmigrant Visa “Integrity” Fee | Fee upon issuance of noncitizens’ nonimmigrant visa by DOS (includes student visas, specialty occupation workers, agricultural workers, etc.) | $0 | $250 | No fee waiver |

| Department of Homeland Security (DHS) Fees | What It Covers | Previous Fee | H.R. 1 Fee (FY 2025) | Fee Waiver or Exemption? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inadmissible noncitizen apprehension fee | Fee for any inadmissible noncitizen who is apprehended between ports of entry by CBP | $50 to $250 civil penalty under 8 U.S.C. §1325(b) | $5,000 | No statutory prohibition but the process to request a waiver is unclear. |

| Ordered Removed in Absentia | Fee for any noncitizen who is ordered removed for missing their immigration court hearing (in absentia)and is subsequently arrested by ICE | $0 | $5,000 | No fee waiver, but exception applies if the in absentia removal order is rescinded |

| Executive Office for Immigration Review (EOIR) Forms or Motions | What It Covers | Previous Fee | HR. 1 Fee (FY 2025) | Fee Waiver or Exemption? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Green Card Application Fee | Fee for noncitizens who have an application to adjust to lawful permanent resident status adjudicated in immigration court | $1,440 | $1,500 | May request fee waiver |

| Waiver of Inadmissibility | Fee for noncitizens whose application for waiver of grounds of inadmissibility is adjudicated in immigration court | $1,050 | $1,050 | May request fee waiver |

| Temporary Protected Status (TPS) | Fee for noncitizens whose application for TPS is adjudicated in immigration court | $50 initial registration $0 for re-registration | $500 | May request fee waiver |

| Filing fee for appeal of Immigration Judge Decision | Fee for any noncitizen who files an appeal of a decision by an immigration judge | $110 | $900 | May request fee waiver; exception applies for bond appeals |

| Filing an appeal from a decision of any adjudicating official in a practitioner disciplinary case | Fee for any practitioner who files an appeal from a decision of an adjudicating official in a practitioner disciplinary case | $675 | $1,325 | May request fee waiver |

| Filing a motion to reopen or reconsider | Fee for any noncitizen who files a motion to reopen or to reconsider a decision of an immigration judge or the Board of Immigration Appeals (BIA) | $145 (immigration court) $110 (BIA) | $900 | May request fee waiver; exception applies if motion is based on an in absentia removal order and there was lack of proper notice |

| Suspension of Deportation Application | Fee for any noncitizen who files an application for suspension of deportation with an immigration court | $100 + $30 biometrics fee | $600 | May request fee waiver |

| LPR Cancellation Application | Fee for any noncitizen who files an application for cancellation of removal for certain lawful permanent residents with an immigration court | $100 + $30 biometrics fee | $600 | May request fee waiver |

| Non-LPR Cancellation Application | Fee for any noncitizen who files an application for cancellation of removal for certain non-lawful permanent residents with an immigration court | $100 + $30 biometrics fee | $1,500 | May request fee waiver |