Over the last decade, a surge in the availability and use of synthetic opioids has led to a staggering toll of overdoses in the United States. From 2013 to 2023, the national drug overdose death rate more than doubled, with drug overdose deaths peaking in 2022 at 107,941. Much of this was due to the rise in fentanyl, a powerful synthetic opioid commonly used for pain management in hospital settings, which was also responsible for 70 percent of overdose deaths in 2023. While overdose deaths have fallen from their record highs, the threat posed by synthetic opioids remains—as does the importance of properly understanding how fentanyl enters the United States.

This fact sheet uses two separate datasets to confirm what has long been reported by law enforcement sources and other researchers: that the majority of fentanyl smuggled across the southern border enters not on the backs of migrants crossing the border on foot, but in the vehicles and on the bodies of U.S. citizens and other lawful entrants seeking admission at land ports of entry. Using two separate datasets described below, we confirm roughly four in five people apprehended for smuggling fentanyl into the United States at the southern border between October 2018 and June 2024 were U.S. citizens—the rest were largely individuals with visas, border crossing cards, or other permission to enter the United States lawfully at a port of entry.

Despite this reality, many Americans falsely believe that migrants are the ones bringing fentanyl into the country. This narrative has been fueled by political rhetoric that seeks to link the issue of migration at the southern border directly with the opioid epidemic. However, this data shows conclusively that the two issues are distinct. Migrants are not responsible for the fentanyl epidemic. Rather, there is bipartisan agreement that efforts to reduce the volume of fentanyl smuggled across the southern border should focus primarily on ports of entry, where millions of people enter every month. Longstanding weaknesses in port security permit transnational criminal organizations to hide small volumes of the powerful synthetic opioid among other lawful trade and traffic and remain the border’s biggest vulnerability to fentanyl smuggling.

Background

Drug smugglers have been bringing drugs into the United States through ports of entry for decades. In 2011, the Department of Justice noted that “Mexican-based [transnational criminal organizations] primarily smuggle cocaine, heroin, and methamphetamine through [ports of entry] in California and South Texas.”

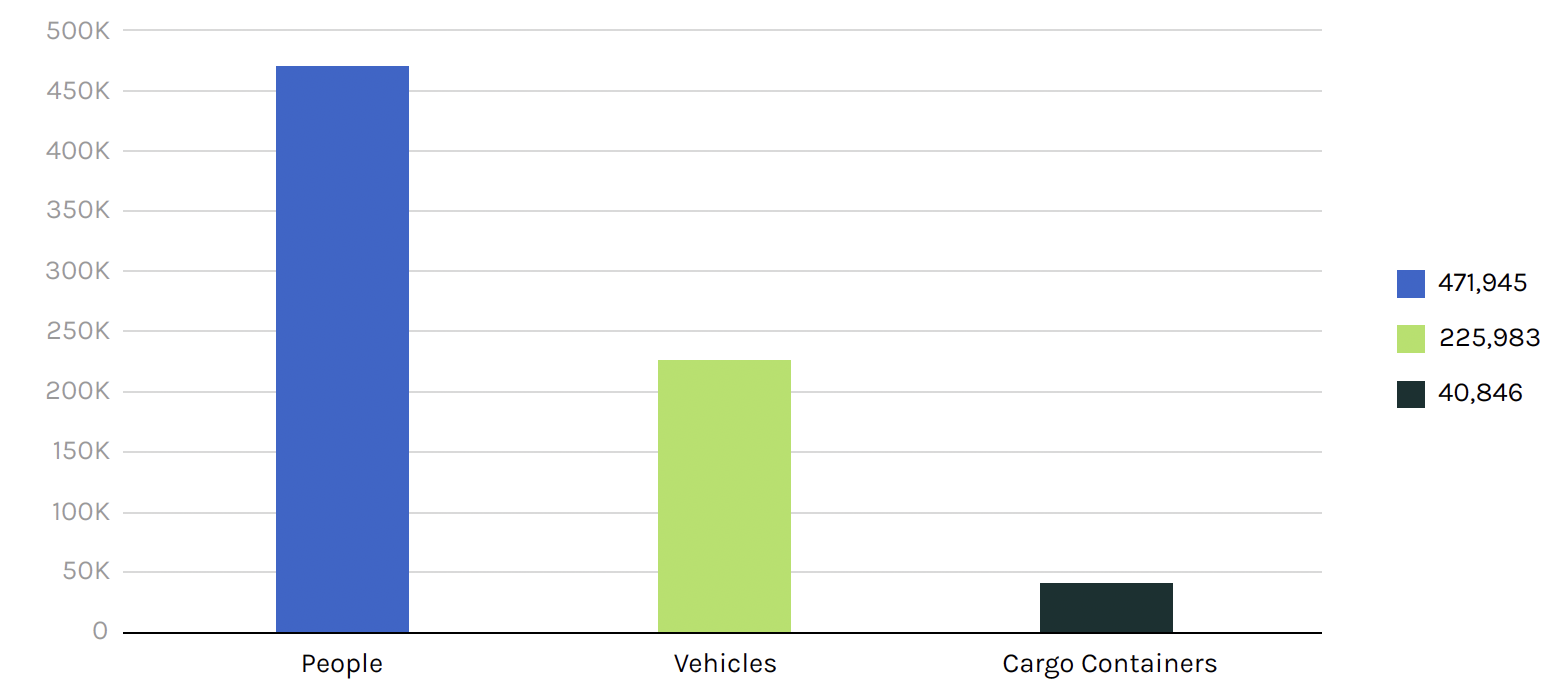

The primary reason that cartels utilize ports of entry is the sheer volume of people and vehicles crossing through ports of entry on any given day for legitimate trade and travel. On the average day in March 2025, 204,241 personal vehicles carrying 361,764 passengers crossed the border, along with 104,926 pedestrians, 21,359 trucks carrying 37,456 cargo containers, 352 buses carrying 5,255 passengers, and 31 trains pulling 3,390 rail cars (see Figure 1).

FIGURE 1: AVERAGE DAILY ENTRIES AT U.S.-MEXICO LAND PORTS OF ENTRY, MARCH 2025

For example, at the Otay Mesa port of entry near San Diego, California, an average of 22,000 vehicles entered each day in December 2024 (including 3,000 trucks). At the nearby San Ysidro port of entry, nearly 40,000 passenger vehicles enter per day. Combined, an additional 29,000 pedestrians crossed at the two ports of entry per day in December 2024.

Most people crossing the land border will not receive intensive screening, because to do so would slow border traffic to a crawl and make it impossible for people and cargo to travel efficiently. Few vehicles passing through southern border ports of entry are subject to any screening for narcotics. Despite years of investments in new technology at ports of entry, as of spring 2024, just 20 percent of commercial traffic and five percent of passenger vehicle traffic were screened through non-intrusive inspection technology. This represented a small but measurable increase from early 2023, when just 17 percent of commercial traffic and two percent of passenger vehicle traffic was screened with non-intrusive inspection technology.

The sheer volume of this traffic, combined with the low chance of any individual person being subject to a more detailed screening, means that criminal organizations can easily smuggle narcotics: concealed with a traveler who is themselves concealed among all the other travelers, safe in the knowledge that only a small portion of people, vehicles, or cargo containers can be searched at any given time.

Official data suggests that this tactic is highly effective for criminal organizations. An annual report submitted to Congress by the Department of Homeland Security in 2023 estimated that U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) stops less than three percent of cocaine smuggled through land ports of entry at the southern border.

While criminal organizations have been smuggling cocaine and other hard drugs across the U.S.-Mexico border for years, fentanyl smuggling is relatively new. Fentanyl was first mentioned as a rising threat in the National Drug Threat Assessment in 2014. In 2013-2014, fentanyl was primarily manufactured in China and then shipped to the United States through the postal service or via Mexico. By 2019, however, China agreed to restrict the manufacture of fentanyl, and production began to shift to Mexico itself, with precursor chemicals smuggled to Mexico which were used to manufacture the drug in illicit laboratories.

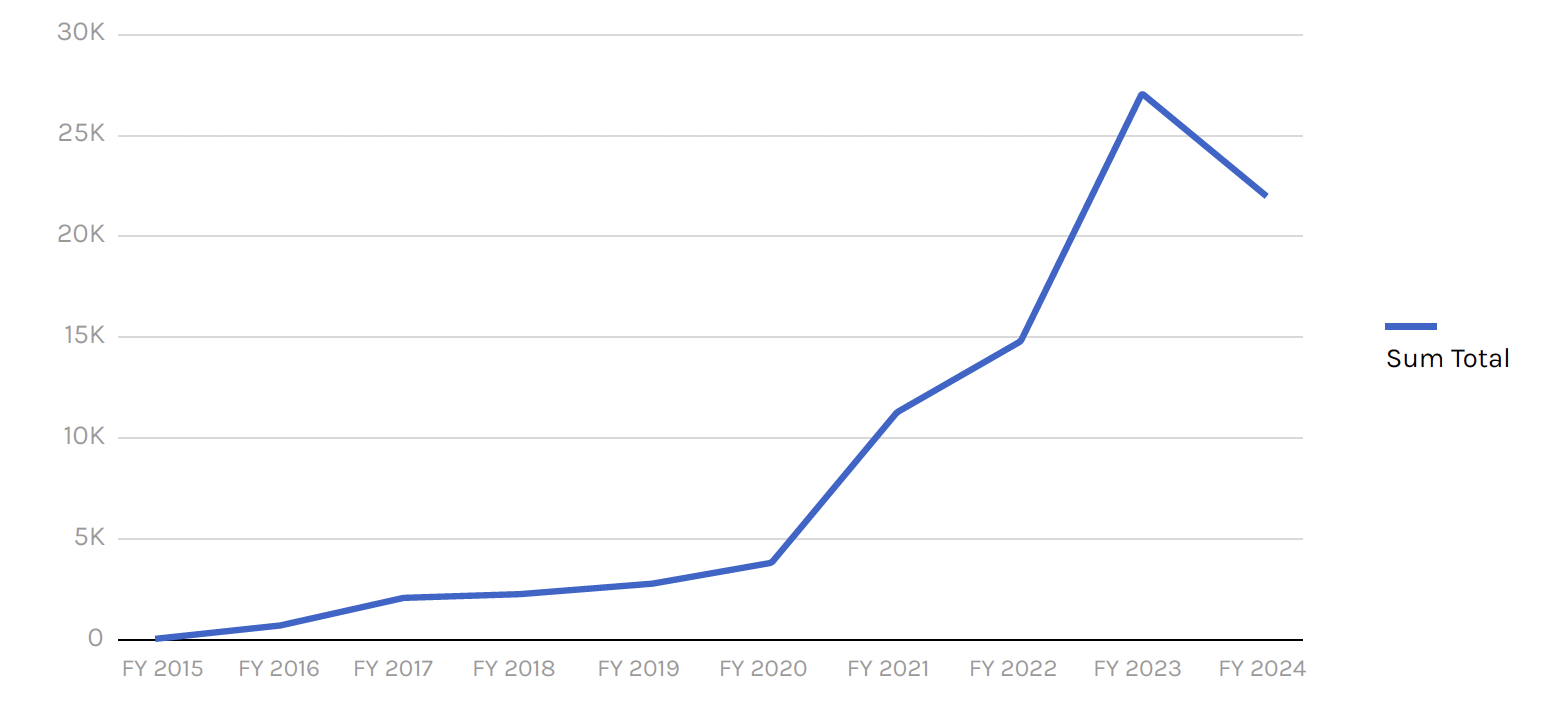

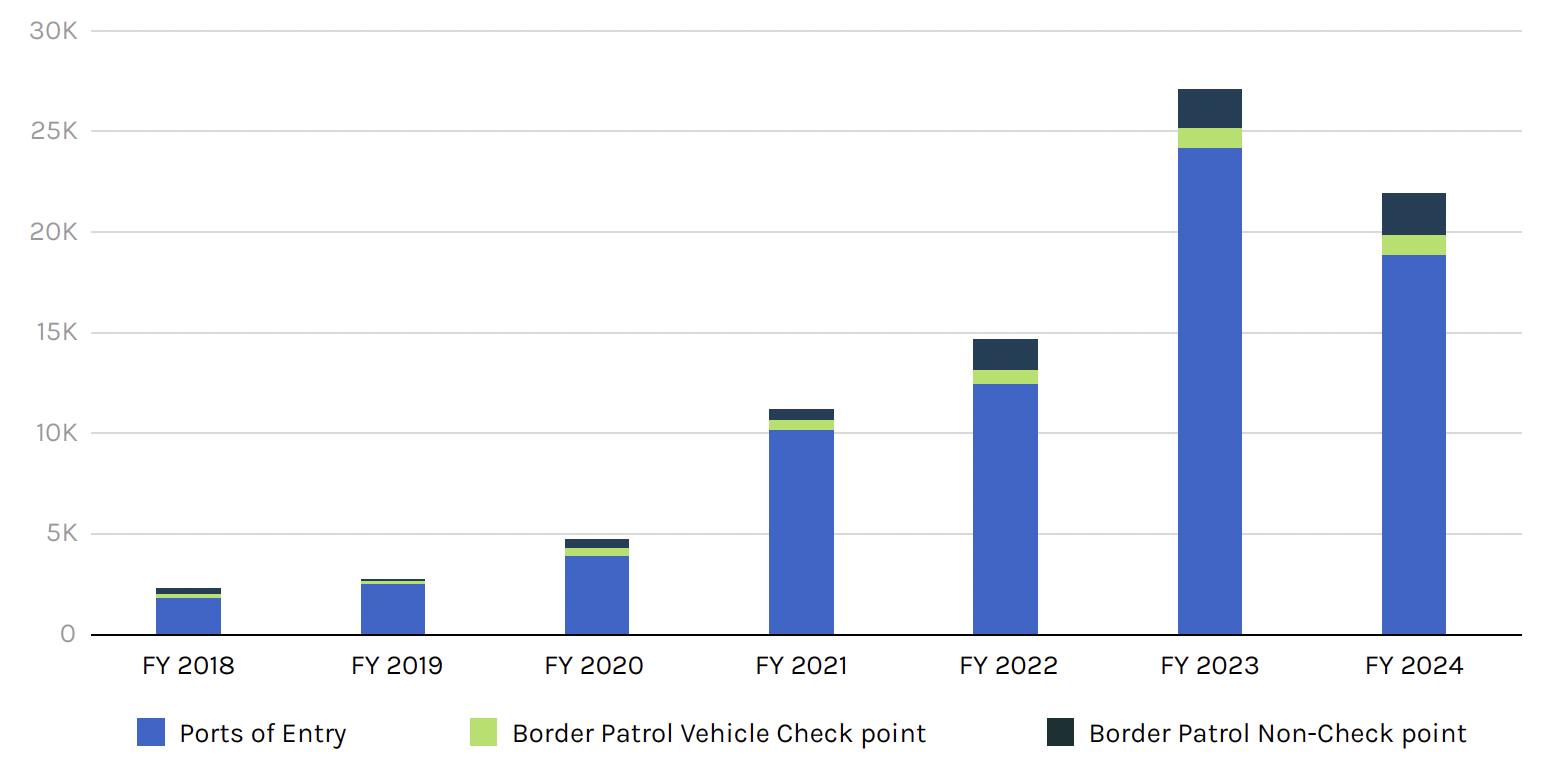

CBP first began publishing data on fentanyl seizures in Fiscal Year (FY) 2015, when the agency seized under 100 pounds of fentanyl. Seizures rose every year that followed, spiking after COVID hit as lower cross-border traffic led to shifts in smuggling patterns and as Mexico became the primary source of fentanyl manufacturing. Seizures peaked at 27,023 pounds in FY 2023 (see Figure 2).

FIGURE 2: CBP FENTANYL SEIZURES IN POUNDS, FY 2015 TO 2024

Importantly, fentanyl seizures peaked in spring 2023 and have been declining since. CBP fentanyl seizures hit record levels in April 2023 at 3,220 pounds. Although the exact reason is not yet clear, seizures fell nearly every month after that, and by March 2025 had dropped to just 760 pounds. This drop in seizures occurred almost entirely at ports of entry, with nationwide Border Patrol fentanyl seizures in April 2025 (133 pounds) remaining at roughly the same levels as April 2024 (140 pounds) and April 2023 (137 pounds), despite dramatically fewer migrant crossings.

Evidence suggests that less fentanyl may be coming into the country because there is less demand for it in the U.S. as opioid overdoses fell dramatically in 2024, with official CDC data through November 2024 showing that overdose deaths dropped in all but two states. Should these trends continue, it suggests the worst of the fentanyl crisis may be behind us.

Where is Fentanyl Smuggled into the United States?

The vast majority of fentanyl is smuggled into the United States at ports of entry, similar to other drugs (less common means include cross-border tunnels, drones, catapults, and on foot). As the head of the DEA testified to Congress in 2023, “Our investigations do tell us that the vast majority of fentanyl is coming in the ports of entry.”

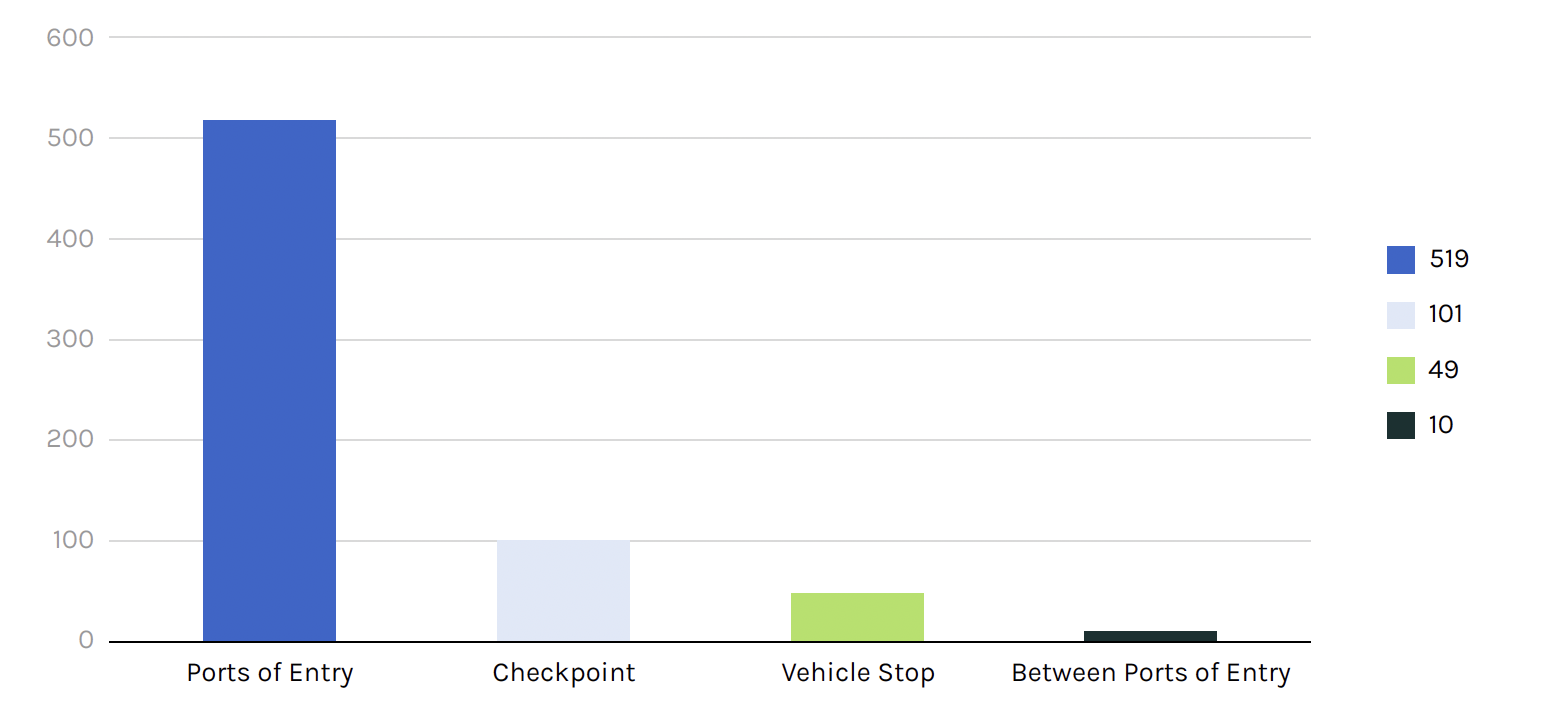

This observation is supported by an American Immigration Council analysis of nearly 700 press releases and social media posts published by CBP between January 2021 and March 2024 touting the seizure of fentanyl at or near the southern border. While these press reports are not a comprehensive source of data on every fentanyl seizure, they allow for researchers to track certain information which is not reported elsewhere, including the location of the seizure and the method by which the smuggler attempted to bring fentanyl into the United States.

In total, 519 press releases identified smuggling incidents occurring at ports of entry, 101 occurred at Border Patrol checkpoints on roads and highways inside the United States, 49 occurred when Border Patrol pulled over a vehicle, and just 10 occurred between ports of entry when migrants were stopped on foot or fentanyl was found abandoned.

FIGURE 3: FENTANYL SEIZURES REPORTED BY CBP, BY LOCATION, JANUARY 14, 2021 TO MARCH 24, 2024

As a result, there is little evidence to suggest migrants are bringing fentanyl across the border on foot—or that migration is linked to fentanyl at all. While some have speculated that high levels of irregular migration provide an opportunity for drug smuggling (on the logic that border agents are distracted), the data provides no support for this theory. Migration has risen and fallen with no correlation between drug seizures.

CBP’s public drug seizure data further supports this fact. From FY 2018 through FY 2024, a seven-year period, over 92 percent of all fentanyl was seized either at a port of entry or at a Border Patrol vehicle checkpoint (see Figure 4).

FIGURE 4: CBP FENTANYL SEIZURES BY LOCATION

Just eight percent of CBP fentanyl seizures occurred at any other location, and as the CBP media releases suggest, the majority of the other Border Patrol seizures were vehicle stops, not migrant apprehensions on foot. These vehicle stops can at times result in very large seizures. For example, in 2022, a single stop of a GMC pickup truck at 3:00 AM in Campo, California resulted in the arrest of a U.S. citizen who was transporting 250 pounds of fentanyl concealed in a spare tire and the vehicle’s gas tank. In total, out of 32 Border Patrol vehicle stops recorded in CBP press releases in which citizenship was reported, 28 involved arrests of U.S. citizens and 1 involved a lawful permanent resident.

Who is smuggling fentanyl into the United States?

Because most fentanyl seizures occur at ports of entry, the majority of fentanyl is smuggled by people who can enter the United States legally. These individuals can evade detection by posing as normal travelers entering or re-entering the United States. As a result, transnational criminal organizations tend to recruit U.S. citizens, who receive the least scrutiny on entry.

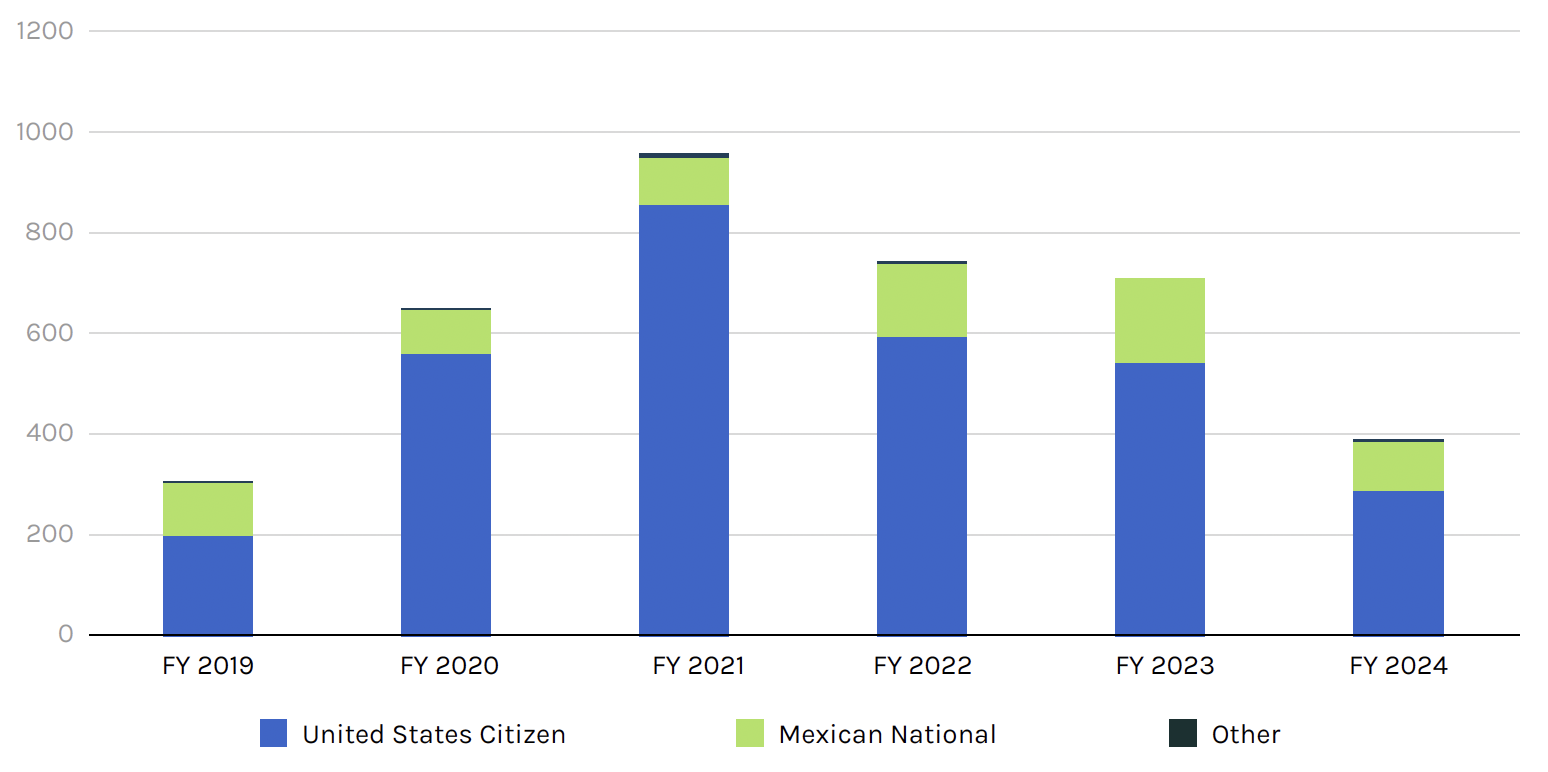

Data obtained through the Freedom of Information Act confirms that most people arrested smuggling fentanyl into the United States at southern border ports of entry are U.S. citizens. In total, 81.2 percent of all seizures at ports of entry along the southwest border (specifically, under the San Diego, Tucson, El Paso, and Laredo Field Offices) from fiscal years 2019 through June 2024 were U.S. citizens (see Figure 5). The FOIA data is supported by the American Immigration Council’s analysis of CBP media releases; of 127 instances in which citizenship status of a person caught smuggling fentanyl through a port of entry was reported, 99 (78 percent) were U.S. citizens.

FIGURE 5: NATIONALITY OF INDIVIDUALS CAUGHT SMUGGLING FENTANYL AT PORTS OF ENTRY, FY 2019 THROUGH JUNE 2024

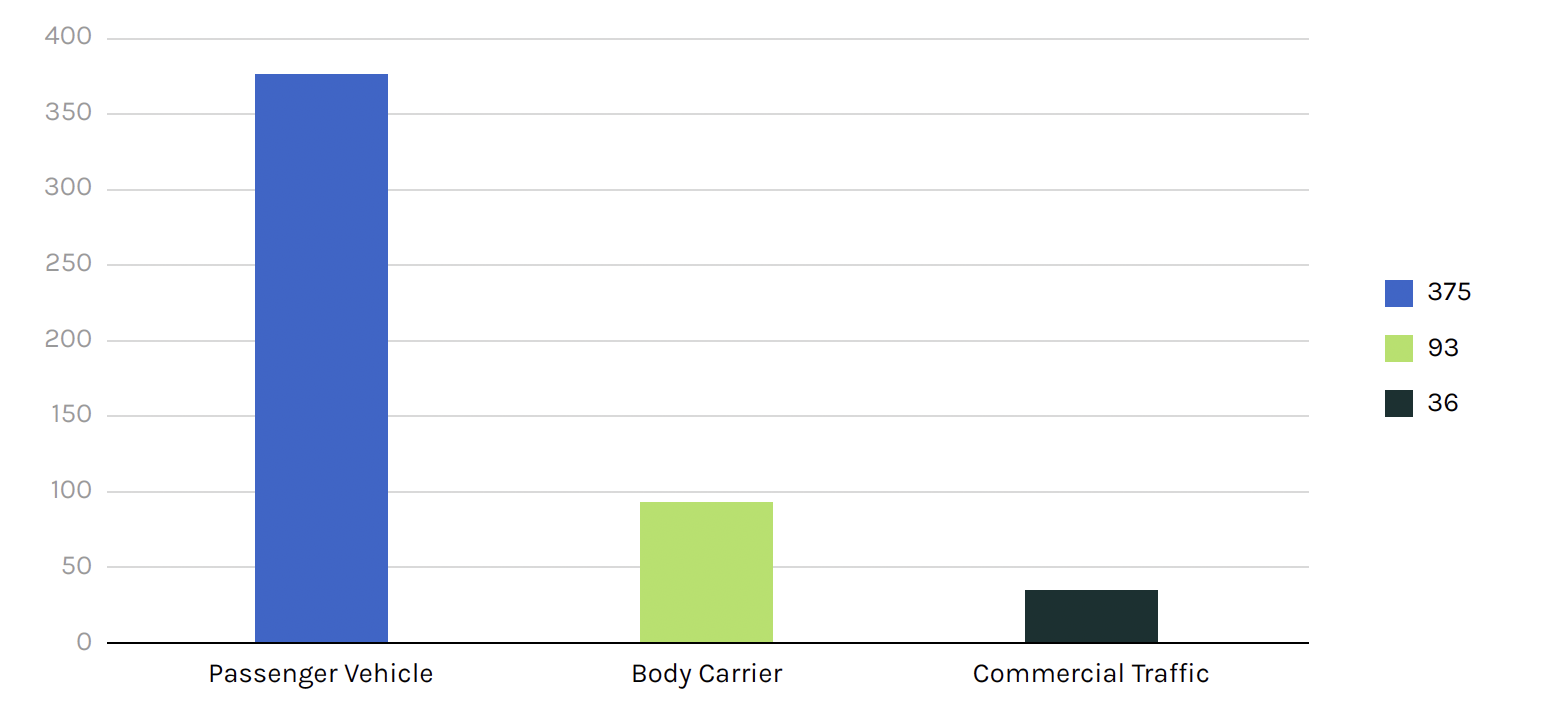

Fentanyl is smuggled through ports of entry in three main ways: on foot through pedestrian lanes, concealed in passenger vehicles, and concealed in commercial traffic. The American Immigration Council’s analysis of CBP media releases found that the single most common method of smuggling was in passenger vehicles, followed by pedestrian traffic and then commercial traffic (see Figure 6).

FIGURE 6: MANNER OF ENTRY, FENTANYL SMUGGLING AT PORTS OF ENTRY

Smuggling methods tend to be creative. For example, over a four-day period in 2023, CBP officers at the Port of Nogales found fentanyl concealed inside the body of one person, in the intake manifold of a motorcycle, and inside a pair of shoes worn by a different person.

The amount of drugs smuggled varies considerably. The American Immigration Council’s analysis of CBP media releases includes pedestrians being arrested for as little as two grams of fentanyl, to one person caught with 33,220 fentanyl pills strapped to his body. Passenger vehicles tend to carry larger amounts, with most seizures involving over five pounds. The largest fentanyl seizure that occurred during this period involved commercial traffic, with nearly 800 pounds of fentanyl found in a shipment of green beans in April 2023.

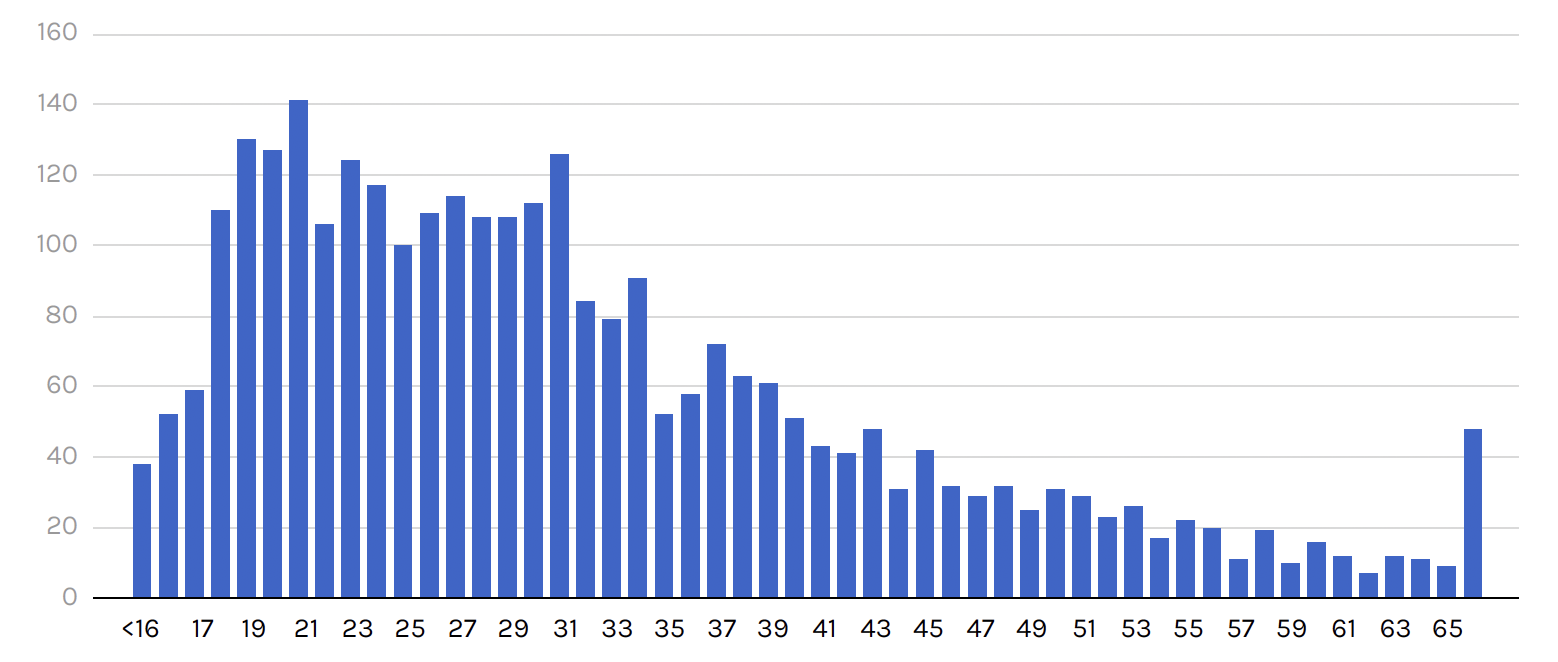

Most of the individuals arrested smuggling fentanyl through ports of entry are young, with the largest share of individuals in their 20s to 30s. (See Figure 7). According to information obtained through FOIA, the median age of U.S. citizens arrested between FY 2019 and June 2024 for attempting to smuggle fentanyl through southern border ports of entry is 30.

FIGURE 7. AGE OF U.S. CITIZENS ARRESTED FOR FENTANYL SMUGGLING BY CBP, FY 2019 THROUGH JUNE 2024

The data above largely aligns with data from the U.S. Sentencing Commission, which reports on the immigration status of individuals who are convicted and sentenced nationwide for trafficking fentanyl. In total, in FY 2023, the most recent data available, 86.4 percent of individuals sentenced for fentanyl trafficking were U.S. citizens, and the average age at sentencing was 34 years.

Profiles of individuals arrested for the offense give a sense of how people are recruited for smuggling. Criminal networks operate sophisticated recruitment schemes that prey on vulnerable people who need money and are potentially willing to commit a crime to get it—promising easy cash, anywhere from $1,000 to $10,000, for a single trip across the border. The lure of money draws many desperate Americans, who travel across the border, meet a contact in Mexico, and are given the drug and sometimes even a vehicle to drive back across the border.

Conclusion

The fentanyl crisis and migration management are different issues, and solving them requires dealing with each issue separately. Addressing fentanyl smuggling has to start at the point where it is most serious: ports of entry. Increasing screening technology at ports of entry will allow CBP officers to catch more fentanyl concealed in vehicles, and hiring more officers will permit more screenings and reduce opportunities for smugglers. This can be combined with public health measures inside the United States that help tackle addiction and law enforcement measures aimed at reducing the power of recruitment networks.

By contrast, placing the blame on migrants seeking protection, and scrutinizing them for fictitious ties to drugs, will have little impact on fentanyl smuggling. It will only serve to demonize a population who have nothing to do with the opioid epidemic.