IN THIS REPORT

- Understanding this administration’s immigration policy

- Who are we allowing into the United States, and who are we excluding?

- How are we treating the immigrants already here?

- Stripping them of legal status and protections

- PROFILE: Axel, a DACA recipient trying to protect his community

- Erecting procedural barriers and blockades for people trying to obtain more permanent legal status, or to maintain their work permits

- Forcing some to choose between criminal prosecution and giving their addresses to ICE

- Bringing the threat of immigration enforcement, and harassment, into any interaction with the government

- Depriving them of support from civil society

- PROFILE: Beatriz, an immigrant lawyer fighting for noncitizen kids

- Who are we forcing to leave, and how?

- There is a better way

Understanding this administration’s immigration policy

The first six months of the second Donald J. Trump administration have arguably seen the most significant changes to U.S. immigration policy in the nation’s history. Taken one by one, as they have been announced or revealed, the effect can be overwhelming: it seems impossible to even comprehend everything that has happened, much less to understand it in a systematic way or to anticipate what might come next.

The purpose of this report is not to recapitulate the last six months of chronology. Nor is it to contextualize the last six months within the history of immigration policy. The administration is simultaneously continuing some policy trends in place under the previous administration; taking latent powers within immigration law and using them as a matter of course; reanimating laws whose enactment predates the modern immigration system; and asserting wholly new powers that have never existed in law before.

Lists like these can make anyone feel as though they have no idea what is actually going on. We aim to do the opposite of that: to provide a framework for the American people to understand what has been done to noncitizens, the communities in which they live, and the entire U.S. immigration system since January 20, 2025. We hope this framework will remain useful as the Trump administration continues its effort to fundamentally transform the American government, character, and role in the world.

Our report is organized as a survey of the immigration policy landscape as of mid-2025, seeking to answer three key questions:

- Who are we allowing into the United States, and who are we excluding?

- How are we treating the immigrants already here?

- Who are we forcing to leave, and how?

We answer these questions both by recounting and analyzing some of the administration’s actions that have shaped the current environment, and by introducing readers to Ilia, a Russian dissident detained in the United States after winning his asylum case; Axel, a Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) recipient trying to plan his career without knowing if he can keep working legally in the U.S.; Beatriz, a lawyer representing young immigrant children like she once was herself; and Kaelyn, whose partner was arrested in the middle of the night and now faces potential removal under the Alien Enemies Act. These profiles, and the stories of others referenced in the report, are a constant reminder that the decisions this administration has made and the way in which they have implemented them have enormous human costs.

On the ground, the answers to these questions are changing day by day—even minute by minute—as new policies are enacted, implementation is tweaked, or judicial injunctions and protracted litigation attempt to maintain the status quo. (One prominent example: this report does not address the Supreme Court’s ruling to partially stay lower-court injunctions of the executive order limiting birthright citizenship, as the effects and implications of that ruling are still unfolding.) The report reflects our best understanding as of its publication, and specific policies described herein may no longer be in effect, or in place in the same way.

However, precisely because policy will continue to evolve for the rest of President Trump’s second term, this report also seeks to identify cross-cutting themes that we believe are particularly important to understand what is being done, and whom it is being done to.

These themes are intended to help the public make sense of changes that can often seem too fast, too sweeping, or too complex to understand—both those that have happened in the administration’s first six months, and those that may come during the rest of President Trump’s time in office.

The immigration policy of this administration can be understood as…

An attack on our democracy

Under this administration, immigration enforcement has run roughshod over rights that most Americans understand to be universal. The First Amendment to the Constitution enshrines freedom of speech as a fundamental right, yet the Trump administration revoked Rümeysa Öztürk’s student visa for writing an op-ed in her student paper criticizing her university’s policy toward Israel. The Fourth Amendment protects against unreasonable search and seizure, but Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agents have engaged in unnecessary secrecy and even subterfuge to seize immigrants off the street. The Fifth Amendment says that no person can be “deprived of life, liberty or property without due process of law.” Nevertheless, the Trump administration has sent hundreds of Venezuelan men to the Terrorism Confinement Center (CECOT), a prison in El Salvador known as a “black hole,” based on secret, flimsy, and unchallengeable allegations that they are members of a gang trying to invade the United States.

Trump’s immigration agenda has served as the tip of the spear not only for attacks on the rights of individuals, but on the structure of constitutional government. This constitutional order is what structures our democracy, ensuring that elected leaders follow the law and respect separate divisions of authority. Power is intended to be spread between the state and federal governments and, at the federal level, across the legislative, executive and judicial branches.

The administration has tested the limits of federalism, deploying the California National Guard without consent of its governor and against U.S. citizens engaging in largely peaceful protests against this administration’s immigration enforcement. It has refused to spend money appropriated by Congress to fund refugee resettlement, provide lawyers to vulnerable children, and help cities and states absorb new arrivals without straining limited local resources. It has prosecuted both appointed and elected officials, including local judges and members of Congress, for allegedly interfering with ICE, and arrested advocates simply for observing ICE operations and immigration court proceedings. And when federal judges—including the Supreme Court itself—have attempted to rein in the administration, the response from the executive branch has been to attack the legitimacy of the judicial branch and the motives of individual judges.

An attempt to overhaul the federal government

At a time when nearly every other function of the federal bureaucracy is being subjected to devastating cuts and overbroad layoffs, the Trump administration is seeking to pour unprecedented money and staffing into immigration enforcement. Agents from at least five federal agencies outside of ICE have been reassigned to immigration enforcement duties; the Department of State has put concerted effort towards revoking visas, especially of foreign students and researchers; and U.S. attorneys around the country have been pressured to put immigration-related prosecutions—against both immigrants and those trying to help them—ahead of all other priorities. Government offices that were supposed to provide some oversight and transparency into the actions of agencies like Customs and Border Protection (CBP) and Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) have been all but eliminated. And as the Trump administration seeks to use government databases to increase its surveillance and control, immigrants have been among the first victims—from a continued campaign to force the Internal Revenue Service to turn over information about immigrant taxpayers to ICE, to declaring thousands of living immigrants bureaucratically dead for the purposes of their social security records.

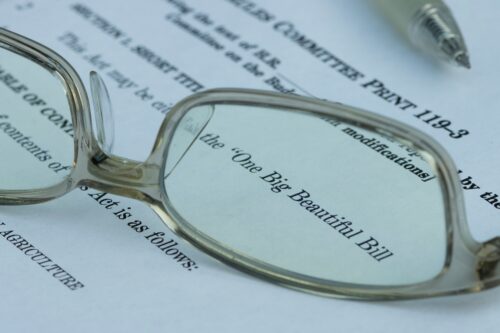

Nothing as big as the federal government can be completely transformed in only six months, and it would have been impossible for the Trump administration to meet its stated goals of arresting 3,000 people per day—much less deporting 1 million per year—even without the litigation setbacks it has encountered and the errors it has had to correct. However, assistance from Congress, in the form of$170.1 billion in new spending for immigration enforcement under the “One Big Beautiful Bill Act” signed into law by President Trump on July 4, 2025, will turbocharge the Trump administration’s effort to repurpose the federal government. This new infusion of money makes ICE the highest-funded federal law enforcement agency in history—funded at a level higher than some foreign militaries—and will bring the administration’s effort of repurposing the federal government to focus primarily on immigration enforcement close to reality.

An exercise in bending reality to match propaganda

Throughout Donald Trump’s political career, Trump and others have vastly overstated the number and nature of undocumented immigrants in the U.S., inventing millions of nonexistent migrants and accusing them of inherent criminality, while erasing the existence of millions of immigrants who have lived in the U.S. for over a decade and have no criminal record. Their insistence that anyone without papers in the U.S. is inherently a criminal is wrong; it contradicts federal law and undermines the contributions that immigrants make to American communities and the U.S. economy.

But while the federal government cannot turn immigrants into bad people just by saying they are, it does have the power to strip legal status from individuals—taking individuals who are legally present and rendering them deportable. The Trump administration has summarily stripped Temporary Protected Status (TPS) from nearly 1 million people and has revoked hundreds of thousands of grants of humanitarian parole. It has also acted aggressively to revoke the status of individual people living in the United States legally (such as students)—and instead of notifying them that they have lost their status, chosen to ambush them with arrest and detention.

Furthermore, the administration has weaponized federal criminal law to treat immigrants in violation of civil immigration law as criminals—and (through other outdated laws) even treat them as an invading army—thus justifying its own propaganda. For example, this administration is prosecuting immigrants for failing to carry proof of registration on their persons at all times, allowing the administration to turn immigrants into criminals and fulfill what they have long claimed.

In press conferences, administration officials have sometimes simply lied or made unproven assertions about an immigrant’s criminal history. But the depiction of immigrants as criminals also shapes the experience of people detained under this administration—a lesson learned by the families of the men sent to CECOT in El Salvador, such as Mervin Yamarte, whose family discovered where he was after several days of worrying when they saw his head being shaved in a propaganda video.

A maelstrom of fear and chaos in service of the administration’s policy goals

Nothing that has happened over the last six months has changed the fundamental truth that arresting, detaining, and deporting every undocumented immigrant in the United States is nearly impossible. Notably, Trump’s second term has distinguished itself from his first with an emphasis on encouraging immigrants to “self-deport” —using harsh policies and promises of money to push them to leave the United States on their own and give up on whatever legal status, or prospects for legal status, they may have.

Just as the U.S. government (under presidents of both parties) has chosen a strategy of treating some people harshly when they are apprehended at the U.S.-Mexico border in hopes that it will deter future migration, the Trump administration’s aggressive tactics have caused immigrants of all legal statuses to constantly worry about their future safety in the United States. Policy changes such as the recission of limiting ICE enforcement at locations such as churches and schools spread worry that no place is safe; stories of people being arbitrarily detained upon returning to the U.S. from trips abroad spread worry that no one is safe.

The chaos is compounded by the administration’s own unforced errors, such as erroneously sending letters telling an unknown number of U.S. citizens and legal immigrants that “it is time for you to leave the United States.” It is further complicated when the administration’s policies are stopped, delayed, or modified through litigation—with someone’s future in the United States often hinging on how a class is defined in a class-action lawsuit or how broadly an injunction is applied.

It will take longer than six months to fully understand the impact of this chaos on American communities. Stories around the country already suggest that chilling effects are not only making immigrants themselves afraid to participate in public life, but affecting the institutions with which they interact, such as universities. Some people have already chosen to leave the United States—but for many immigrants here, there is no real alternative to staying and waiting.

A radical revision of America’s place in the world

One of the forces driving U.S. immigration policy has always been the image of itself that America wishes to project to the rest of the world—declaring who its allies and enemies are and making a claim to its own exceptionalism. This has been most obvious in the U.S. refugee program, which for decades resettled more refugees in new permanent homes than any other country in the world. How the U.S. attempted to balance enforcement of immigration law at its borders with its humanitarian commitments sent a signal to other countries about what was acceptable. Availability of visas for researchers, teachers, and doctors (for example) allowed the United States to retain a reputation as the biggest hub for global talent.

The Trump administration has openly rejected the longstanding consensus about America’s place in the world, seeking to overhaul everything from defense alliances to international trade. One can get a robust understanding of the administration’s view for American global leadership by looking at immigration.

The United States Refugee Admissions Program (USRAP) has been summarily abandoned, destroying an ecosystem of organizations and communities—often led by refugees themselves—who worked to welcome newcomers to America. The administration plays hardball with some countries to force them to accept deportation flights, threatening visa sanctions on Colombia after it refused to allow a military plane to enter its airspace. It has embraced world leaders who assist with its efforts to get people out of the United States—such as President Nayib Bukele of El Salvador—who previous administrations held at arm’s length due to their repressive domestic policies. The State Department’s human rights alerts will reportedly no longer criticize countries for returning people to persecution, or for preventing their own residents from leaving.

Meanwhile, the administration has dealt the final blow to the U.S.’ own commitment to the Refugee Convention, by fully militarizing the U.S.-Mexico border and offering no opportunity whatsoever to seek protection from the United States by presenting oneself to border authorities. This has happened with little fanfare—partly because crossing levels remain low, and partly because pathways to asylum have been successively narrowed by administrations of both parties over the last several years. In the past, however, the United States at least professed to uphold the idea that no one should be returned to a country that will persecute or torture them—a principle that current officials are uninterested in paying even lip service to.

The message is that America under Trump is uninterested in global leadership driven by immigrant workers, researchers and entrepreneurs, and that it is no longer a safe place for people to live. Already, other countries are seeking to respond to the Trump administration—by working with it, or by taking a stand against it—in ways that will affect whether people choose to move to those countries instead of migrating to the United States in the future. How America’s immigration policy shapes our global reputation is not something that can easily be teased out in six months, but the seeds of the next several years, or even decades, have been planted.

Who are we allowing into the United States, and who are we excluding?

On the first day of the second Trump administration, a barrage of executive orders gave the impression that the United States was making a radical U-turn in its immigration policy: from a supposed open-borders policy that had allowed an unspecified “invasion” of migrants into the United States to an attitude that the border was now “closed.”

The reality is somewhat less dramatic and more complicated.

Policy at “the border”—which is to say, enforcement of immigration laws against people trying to enter without authorization—has become entangled over the last decade with policy regarding asylum. The western hemisphere has seen significant shifts and increases in migration, driven by ongoing humanitarian challenges, while the U.S. has failed to update its laws to address new realities. Presidents of both parties have sought to restrict access to asylum; on the eve of Trump’s inauguration, it was already nearly impossible for someone to qualify or even file an application for asylum after entering the U.S. between ports of entry. Trump, declaring unequivocally that no humanitarian protection would be available to anyone entering at the U.S. southern border, delivered the death blow to a commitment to asylum that had been weakened by his previous administration as well as President Biden’s.

The Trump administration paired its asylum ban with an effort to prevent the United States from screening and resettling refugees or other humanitarian immigrants. The refugee ban, accompanied by an effort to destroy an entire ecosystem of nonprofit organizations that seek to welcome and integrate newcomers, has left 100,000 or more people around the world in limbo. The administration made a concerted effort to find and fast-track white South Africans for refugee resettlement over a matter of weeks, while ignoring over 20,000 refugees who had made it through a years-long process and had already booked travel to the United States when the ban came down—including one Congolese refugee woman who, ironically, is stuck in South Africa waiting to be reunited with her mother after decades of separation.

The refugee ban has left 100,000 or more people around the world in limbo.

This sends a clear message to the world about the United States’ priorities, and its abandonment of its commitment to the U.S. asylum system, the refugee conventions, and the Refugee Act of 1980. In the six months prior to Trump’s inauguration, the U.S. admitted over 59,000 refugees; the Trump administration has spent most of its first six months fighting court orders to admit a few hundred.

The Trump administration has also created new barriers to legal immigration—such as imposing a new system of country-wide “travel bans” barring entry for anyone from 12 countries, and severely curtailing entry for people from 7 additional countries. However, other barriers to legal immigration under this administration are likely to be procedural, individualized, and arbitrary—making them harder to identify.

Overall levels of new visa issuances did not significantly fall during the administration’s first few months, with both immigrant and nonimmigrant visa issuances comparable to their 2024 levels through April 2025. (Notably, this data precedes the implementation of country-level travel bans.) However, the Trump administration’s desire to reduce the federal workforce responsible for processing legal immigrants—while those same employees also take on immigration enforcement duties—suggests that we may begin to see effects of the changes made over the first six months on levels of visa issuances and processing times over the coming years.

From few asylum-seekers to none at all

The slow death of asylum

Since the 1950s, it has been a principle of both U.S. and international law that the government cannot return someone to a country in which they will be persecuted or tortured. Asylum and lesser forms of protection (such as withholding of removal and protection under the United Nations Convention Against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman, or Degrading Treatment or Punishment) are processes that Congress created to make sure the U.S. government was following its own laws. Fixes have had to be made to asylum policy over time, to ensure that a proper balance was being struck between the government’s authority over immigration and its fealty to its principles.

Since the second term of the Obama administration, however, U.S. asylum policy has become hopelessly entangled with border management. As part of global displacement challenges, many more people than ever before started coming to the United States to request asylum; at the same time, those people came from places beyond Mexico and had more complex needs than the working-age adults who had made up most migration in the past.

Faced with a political narrative demonizing asylum seekers and bottlenecks in the system for processing and adjudicating asylum claims, elected officials decided it would be harder to improve the speed and efficiency of the system than it would be to stop people from coming to begin with—a “deterrence” goal that has guided presidents of both parties for the last decade, to no lasting success, and with massive opportunity cost. (For more on the asylum system and border management, see the American Immigration Council report Beyond A Border Solution.)

The Biden administration ran headlong into the limitations of prioritizing deterrence over processing. For the first half of President Biden’s term, he kept in place the Title 42 policy which allowed the government to expel asylum-seekers with no effort to hear their claims whatsoever—even though it was quite clear that no one believed the official public health justification for the policy remaining in place. Evidence showed that Title 42 had little overall deterrent effect, and, in fact, border apprehensions were much higher in the weeks before Title 42 was lifted than the weeks immediately after. Even while Title 42 was in place, many people were not subjected to it; by the last months of the policy, tens of thousands of people per month were allowed to stay in the United States and pursue asylum cases, as enforcement measures became overwhelmed. That number swelled to over 100,000 per month in fall 2024, when migration levels rose months after the recission of the Title 42 policy.

These individuals were often left with no support or guidance, and no ability to legally support themselves during their first months in the U.S.; major cities like New York City, Chicago, and Denver found themselves challenged to accommodate newcomers with little help from the federal government. To many policymakers, this became evidence that the U.S. was letting in too many people and underscored the need for restrictions on access to asylum.

After erecting significant procedural barriers to asylum eligibility in 2023, the Biden administration issued a declaration of emergency in summer 2024 that explicitly barred asylum to anyone who crossed between ports of entry until overall border crossing levels were substantially reduced. The vast majority of those who were unable to make an appointment at a port of entry via the CBP One app, or who couldn’t wait, were deported without question unless they proactively told a border official they were afraid of returning to their home country (though many officers ignored such statements); even then, they were eligible only for partial protection from deportation and given no access to permanent legal status.

President Trump squeezed that narrow opening shut. In an executive order signed the first day of his second term, he declared that anyone who was part of the “invasion” of the United States (which appeared to include anyone crossing from Mexico without permission) was barred from receiving any benefit under the Immigration and Nationality Act, including asylum. (During Trump’s first term, an effort to restrict asylum along similar lines had been struck down in court, in part because immigration law clearly states that asylum is available to those entering the U.S. “whether or not at a designated port of arrival.”)

Litigation is pending regarding Trump’s executive order and its restrictions on asylum at the border, while the Biden administration’s regulation first creating the “emergency” regime of asylum restriction was enjoined in a separate lawsuit in May 2025.

No asylum between ports of entry—but none at ports of entry, either

Biden’s restrictions on asylum for people who crossed the border without permission were paired with encouragement to use “alternate legal pathways”—avenues that allowed the government to control how many people were coming in and check their identities at the beginning of the process, while allowing them to seek asylum or other protections once they got to the U.S. The Biden administration encouraged people to use the CBP One app to schedule appointments at ports of entry to be screened and potentially begin their asylum cases. This restored predictable, though limited, access at ports of entry after years of efforts to choke off access and prevent asylum-seekers from setting foot on U.S. soil. It also encouraged the use of humanitarian parole programs—such as the Cuban, Haitian, Nicaraguan and Venezuelan (CHNV) parole program and family reunification parole.

The number of CBP One appointments that were available each day along the U.S.-Mexico border gradually expanded over the course of the Biden administration, ultimately reaching 1,450 a day, but never came anywhere near meeting demand. Wait times under the app often stretched as high as eight to nine months in some regions. While waiting in Mexico, asylum-seekers were extremely vulnerable, often running out of money to feed their families and getting harassed by local police. In many cases, asylum-seekers were subjected to rape and assault, or kidnapping at the hands of criminals or police. Yet hundreds of thousands of people were willing to wait for a chance to come to the U.S. without breaking any laws.

To some policymakers, however, the additional screening and orderliness made no difference; they criticized the CBP One app as a “concierge service” for “illegal” migration. The “Securing Our Borders“ executive order shut down the app’s asylum appointment function—cancelling 30,000 appointments that asylum-seekers had been waiting for, and stranding a total of 270,000 people waiting in Mexico for a chance for asylum that may never come. Margelis Tinoco, an asylum-seeker from Colombia who had an appointment for late on the day of January 20, instead had to tell her 13-year-old son “They blocked it. There’s nothing we can do.”

After ending the CBP One app process, the Trump administration did not replace it with anything else. Migrants who go to a port of entry are turned away and not permitted to start the asylum process. As of the writing of this report, there is effectively no legal means to seek asylum at the U.S. southern border.

People who do manage to make it onto U.S. soil (by entering between ports of entry) are invariably detained, with no assessment of whether they pose a flight or public safety risk. The Trump administration has reduced the availability of bond for immigration detainees and made it essentially impossible for current detainees—even those who entered before January 20 and are found by an immigration judge to be eligible for relief—to secure their release from detention even after they have won their cases.

The threat of additional border measures—with hardly anyone to enforce them against

The “Guaranteeing the States Protection Against Invasion” executive order already shuts down asylum access at the U.S.-Mexico border and allows the Trump administration to summarily deport anyone apprehended while crossing. Nevertheless, the administration has layered on additional policies to further punish irregular migration and prohibit asylum.

The administration has promised to resume the “Remain in Mexico” policy, which sent asylum-seekers to wait in dangerous conditions in Mexico while their immigration cases were pending. It remains unclear how this would interact with the executive order summarily barring those same people from being able to seek relief in immigration court, and it does not appear that large numbers of people (if any) are being returned to Mexico under this policy (although some non-Mexicans continue to be deported to Mexico). Additionally, the administration has threatened to revive the Title 42 policy, though the public health grounds on which it would ostensibly be invoked have not been made entirely clear.

One threat the administration has followed through on is the full militarization of parts of the U.S.-Mexico border. The executive order “Clarifying the Military’s Role in Protecting the Territorial Integrity of the United States” directed U.S. Northern Command (NORTHCOM), the regional military command tasked with operations in North America, to “seal the borders.” In late April 2025, in an unprecedented move, the Trump administration ordered over 10,000 members of the armed services to redirect their work to the border, with 7,500 actually deployed there (three times the number who had been deployed to the border on January 20, 2025).

Federal law prohibits use of the military for domestic law enforcement—including immigration enforcement—but the administration has attempted to find a way around this rule. It declared two zones, one along 170 miles of the border in Arizona and New Mexico and one along 60 miles of the border in West Texas, to be “extensions” of nearby military bases—thus allowing military officers to arrest anyone who sets foot in those zones for trespassing on the “base.” (According to military officials, anyone apprehended under these policies is taken into custody by U.S. Border Patrol, not by servicemembers themselves.)

The administration has not succeeded in using this gambit to successfully prosecute migrants as criminal trespassers—one judge threw out 98 cases, saying the government had failed to establish that the border-crossers knew they were “on” a military base. However, the tactic allows the administration to say it is using the military to secure the border—and to push up against the limits of permissible use of the military on U.S. soil.

Trump’s use of multiple and simultaneous restrictive border policies (and Biden’s similar but far less severe strategy) obscure an important fact: unauthorized border crossings have steadily decreased since the beginning of 2024. DHS statistics show that southwest border “encounters” have remained under 15,000 a month since February 2025—down from a December 2023 peak of over 300,000. Part of this is likely due to the Mexican government’s efforts to interdict migrants before they reach the United States, but much is likely a result of a typical ”wait and see” period in which migrants and asylum seekers temporarily wait to travel to the U.S. until the effects of a new policy or political change have become clear. The Trump administration has piled border deterrent policies on top of each other despite the fact that there are apparently few people to deter.

Ilia, young Russian dissident facing never-ending detention

Ilia is a 24-year-old pro-democracy activist who recently fled a threatening environment in his native Russia. But after escaping, he was taken into custody and put into jail-like detention by the very country he believed would protect him: the United States.

“I fled Russia because of increasingly harsh laws, because of a government that started persecuting me for my political views and my sexual orientation,” says Ilia. “I believed the United States would help me.”

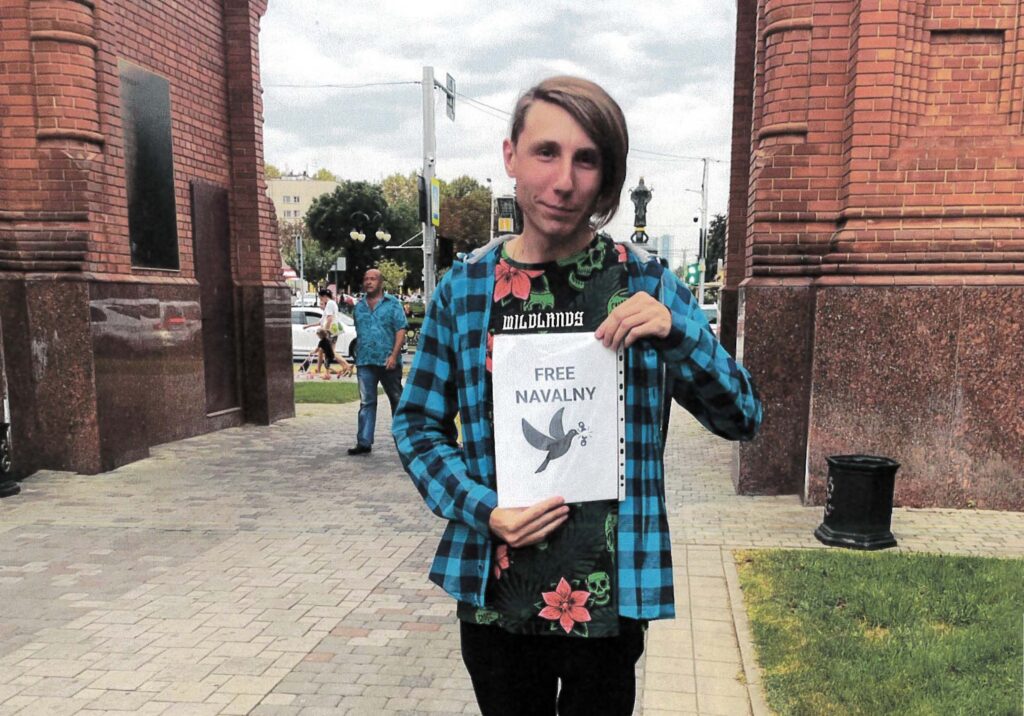

Like many critics of the Putin regime, Ilia was outraged when Russian authorities arrested pro-democracy opposition leader Alexei Navalny in January 2021. In response, he joined nation-wide protests and began putting up “Free Navalny” fliers around Krosnodor, the city in southern Russia where he was a university student. The government response was brutal, with thousands of people detained and many beaten or tasered by police. In February 2024, Navalny died under suspicious circumstances in a Russian prison camp.

By then, Ilia had already fled the country, after receiving threats from Russian intelligence officials. Being nonbinary, he faced additional risk under Putin’s increasingly repressive laws; his mere existence could mean persecution or imprisonment.

Ilia made his way to Mexico, where he followed the asylum process to the letter. He spent eight months near the border, waiting for a CBP One appointment. In May 2024, he arrived for his appointment, ready to make his case. Instead, he was taken into custody on the spot and put into detention, ending up at a Louisiana facility known for abuse and neglect.

“I applied for asylum because I believed the U.S. would help me,” Ilia says. “But once I was sent to Winn Correctional Center in Louisiana, I faced horrible treatment. The way officers treat detainees is awful. They yell at them, sometimes go as far as to discriminate, make racist remarks, and even subject detainees to sexual abuse.” Ilia has filed multiple complaints over the year he’s spent at Winn, but they go unanswered.

Though detained before President Trump came into office, Ilia has experienced the Trump administration’s hardline immigration stance firsthand. In March 2025, Ilia won his asylum case after an immigration judge considered 900 pages of evidence, including threats from Russian intelligence and letters of support from people who’d witnessed his activism. At this point, Ilia should have been released from detention and allowed to start building his life here. Instead, the Trump administration is refusing to let him out.

Ilia has no criminal history and does not pose a threat to his community. In fact, he won his asylum case, because he was targeted for upholding the very democratic ideals of free speech—upon which this country was founded. The result is prolonged, needless suffering, even for those the system has already deemed worthy of protection.

“The situation [in the detention centers] has gotten worse,” Ilia says, explaining that the facility where he is being kept has been at maximum capacity since Trump took office. “People have started to realize there’s no way out, that they’re just waiting here to be deported, and they’re losing their minds.”

Hardly any refugees—with one significant exception

As of January 20, there were approximately 100,000 refugees in the U.S. Refugee Admissions Program (USRAP) pipeline—most of them referred by the office of the UN High Commissioner on Refugees. 12,000 of these individuals had made travel arrangements and were counting down the days to start their new lives in the United States via this program. Many had sold all their possessions in preparation to move to their new home and lives.

Established in 1980, the U.S. Refugee Admissions Program is a complex enterprise requiring several government departments and nonprofit contractors across the globe to coordinate a complex vetting process with multiple moving parts. (For example, would-be refugees need both medical and security clearances, and need to get both at the same time before either expires.) To manage this system, Congress appropriated $4 billion in funds for the refugee program for the current fiscal year.

With Trump’s second inauguration, all of this was abruptly shut down.

The refugee program has traditionally enjoyed bipartisan support in Congress and among community leaders. It has often been a way for Americans to demonstrate their commitment to welcoming newcomers, as well as a way for the United States to retain humanitarian credibility on the world stage. Before 2016, it was typical for the U.S. to admit 70,000 refugees or more per year, with admissions hitting 100,000 in the last year of the Obama administration.

The refugee program was a target of the first Trump administration, which paused admissions in 2017 and significantly reduced the program’s capacity over four years in office. Former Trump chief of staff John Kelly said that the ideal number of refugees he would admit would be “between zero and one”; the administration came close to that in 2020, when it set a target of 18,000 refugee admissions and then admitted only 11,000 (in part due to the outbreak of the COVID pandemic). Accordingly, the administration reduced its support for organizations in the United States that are responsible for placing and integrating refugees, providing them with English lessons, housing, and job training for their first months in the U.S. Without federal contracts, those organizations were forced to lay off massive amounts of staff, sacrificing institutional knowledge.

President Biden arrived in office with promises to expand refugee admissions to surpass even Obama-era levels—promises which, in the context of the nearly-demolished system Trump had left, seemed unrealistic. However, in fiscal year 2024, the United States indeed resettled more than 100,000 refugees—in large part due to an increase in refugee processing in Latin America, a historically neglected region where refugee processing was belatedly pursued as another alternative to irregular migration to the U.S.

This second time, Donald Trump may choose to demolish refugee admissions forever. The current “pause” on refugee admissions, enacted via an executive order titled “Realigning the United States Refugee Admissions Program,” is indefinite, lasting until the program is redesigned to admit only “those refugees who can fully and appropriately assimilate into the United States.” The president himself will make the final decision on whether resuming the refugee admissions program “would be in the interests of the United States.” This runs contrary to the U.S. Refugee Act of 1980 passed by Congress, which establishes the existence of the refugee admissions program and requires the president to notify Congress on an annual basis about how many refugees the administration will try to admit in the coming year.

The attack on refugees abroad also hurts American communities. Within hours of the signing of the executive order, organizations around the United States were told that their federal funds were being frozen, and not to incur any further expenses. This prevented them from being able to provide services for refugees already living in the United States—imperiling their successful integration. One gay Iraqi refugee moved to Dallas in January 2025 with $120 in his pocket, having been promised that he would be given cash assistance for his first few months in the U.S. to build a new life in safety. But when his benefits were suspended in February, he struggled to imagine how he could survive in the United States, and had to consider going back to Iraq where he knew his life would be in danger.

After a federal judge ruled that the administration must unfreeze the funds for resettlement organizations, the executive branch instead terminated their contracts. Organizations have had to furlough or lay off hundreds of employees, leaving many clients like the Iraqi refugee without adequate support. The legality of this funding freeze remains contested in court.

While a federal court initially ordered the government to admit everyone who had been granted conditional entry under USRAP and had arranged travel to the United States prior to the ban, the courts are currently haggling over how many people the administration is actually obligated to admit. Meanwhile, some refugees who were scheduled to arrive in the United States during the first travel ban, in 2017, are still awaiting admission.

The South African exception reveals the administration’s true agenda

On February 7, 2025, President Trump signed an executive order directing the government to resettle white South Africans who claimed they were victims of racial persecution from the country’s Black majority. Barely three months later, 49 such people deplaned for new lives in the United States.

The one exception to the refugee ban—granted by the Trump administration as it argued in court over its obligations to admit even 160 of the refugees who were supposed to arrive in the U.S. in the days after Trump’s inauguration—shows how flimsy the administration’s pretext for gutting the refugee program really is. While two years of vetting is apparently insufficient for most refugees, a group of white farmers claiming persecution at the hands of a majority-Black country is presumed by this administration to “be assimilated easily” into the U.S. after scarcely any vetting at all.

While two years of vetting is apparently insufficient for most refugees, a group of white farmers claiming persecution at the hands of a majority-Black country is presumed by this administration to ‘be assimilated easily’ into the U.S. after scarcely any vetting at all.

Some Afrikaner refugees received preliminary approval even before two U.S. officials flew to Pretoria to conduct interviews, according to a report from Reuters. Officials told Reuters that “there is administrative pressure to approve” applicants. Some refugees’ claims of racial persecution were reportedly based on loss of property, even though economic harm is not generally considered sufficient to demonstrate persecution.

Trump and his officials have intentionally drawn a contrast between the thousands of stranded refugees from around the world and those eagerly recruited from South Africa’s white Afrikaner community. These South African refugees arrived in the U.S. on a chartered plane, for a public event where they were welcomed by U.S. officials who said they were “very welcome” in the United States and had been chosen in part for their ability to “be assimilated easily” within American culture. Trump and other officials have accused the South African government of engaging in ”genocide.” It is a fight they appear eager to pick on the global stage.

To some of the most ardent supporters of the United States’ refugee program, the Afrikaner exception was an unbearable insult added to the injury the Trump administration has inflicted on the longstanding commitment to refugees around the world. Episcopal Migration Ministries canceled its government contract rather than allow it to be used to resettle white South Africans; the presiding bishop said it was “painful to watch” the preferential treatment given to Afrikaners while thousands of people remain languishing “in refugee camps or dangerous conditions for years.”

Travel bans alongside more subtle barriers

The second Trump administration has reinstated its first-term policy of national-level “travel bans” that essentially prevent anyone from a certain country from obtaining a visa to enter the United States or entering it legally. During the first term, restrictions on seven countries—five of them majority-Muslim—prevented thousands of U.S. citizens from reuniting with their families.

The June 4, 2025, proclamation bans issuance of all visas to nationals of 12 countries: Afghanistan, Burma, Chad, the Republic of Congo, Equatorial Guinea, Eritrea, Haiti, Iran, Libya, Somalia, Sudan, and Yemen.

Afghanistan

Afghanistan

Burma

Burma

Chad

Chad

the Republic of Congo

the Republic of Congo

Equatorial Guinea

Equatorial Guinea

Eritrea

Eritrea

Haiti

Haiti

Iran

Iran

Libya

Libya

Somalia

Somalia

Sudan

Sudan

Yemen

Yemen

Seven other countries—Burundi, Cuba, Laos, Sierra Leone, Togo, Turkmenistan, and Venezuela—are subjected to lesser visa restrictions. Nationals of those countries cannot be issued immigrant visas (visas issued for people who will be allowed to permanently settle in the United States) or some categories of non-immigrant visa such as student and tourist visas, but can be issued certain other visas (such as H-1B work visas or ”fiancé visas”) as long as they are only valid for the shortest possible time.

The new travel bans are ostensibly intended to prevent the entry of people who cannot be sufficiently vetted thanks to their home countries’ policies, or who are particularly likely to overstay their visas. However, even though the bans were enacted shortly after an Egyptian asylum applicant (who had overstayed his initial tourist visa) committed an attack on a Jewish event in Colorado, Egypt was not included on the list of banned countries—with Trump saying the Egyptian government “has things under control.” Additionally, the Republic of Congo was included under the ban, while the Democratic Republic of Congo—with higher rates of visa overstays—was not.

In 2023, the U.S. issued approximately 34,000 immigrant visas and over 125,000 non-immigrant visas that would now be prohibited under the current ban. 4.3 million people from those countries living in the United States—including 2.4 million citizens—will no longer be able to sponsor their relatives to come live with them, or even host them for visits, while the travel ban is in effect.

Beyond preemptive and categorical bans on whole national populations, the Trump administration has made clear that all individual applications will be subjected to higher levels of scrutiny. Both the U.S. State Department (responsible for issuing visas to enter the United States) and U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (which adjudicates applications for immigration benefits) have rolled out policies for aggressive ideological screening of applicants. Applicants for student and other visas are now required to have their social-media profiles set to “public” so that administration officials can scrutinize their posts.

Policies such as these increase the possibility of arbitrary and unexplained denials. Furthermore, they create more delays in adjudicating every type of application. From the outside, those delays can become so bad that it is impossible to know for sure whether an application is actually being processed at all. Under the first Trump administration, refugees and others—including applicants for Special Immigrant Visas (SIVs) who assisted U.S. troops in Iraq and Afghanistan—were often subjected to unaccountable and indefinite delays due to a mysterious interagency review process that required additional advisory opinions in certain cases. Because the application could not move forward without affirmative approval, unclear or vague results of these checks could keep applicants in limbo forever without knowing the justification for the delay.

The first Trump administration made it easier for adjudicators to reject applications out of hand. For example, leaving any space blank on an application led to an automatic denial, even if it was not a field the applicant needed to fill out (a policy this administration has reinstated during this term). It also substantially increased requests for additional evidence and notices of intent to deny applications. Both of these tactics prolonged the process and increased the overall rate of denials.

In theory, such restrictions should lead to decreases in the number of visas being issued by the U.S. State Department, and immigration applications being approved by United States Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS). What little information we have so far suggests that there has not been a dramatic change in visa issuance, at least, in the first few months of the Trump administration (before the travel bans were issued). In February, March and April 2025, like the same months in 2024, U.S. embassies and consulates issued around 50,000 immigrant visas each month, and around 1 million nonimmigrant visas. While April 2025 did see a slight (16 percent) downturn in immigrant visa issuance compared to the previous year, it is impossible to know without more data whether this signals the beginning of a trend.

It is very difficult to know how internal processing of immigration applications and petitions has changed in the first six months of the second Trump administration for two main reasons. The first is that six months is a very short period of time in the legal immigration system, and limited data is available to identify any new trends. Several U.S. embassies have wait times of over a year for appointments for interviews for tourist visas. Processing times at USCIS routinely tick above six months—and published processing times always exclude the cases that are taking the longest to resolve. And, of course, the wait for immigrant visas for certain family members from certain countries can be measured in decades. The eligibility dates for family-based visas in the monthly Visa Bulletin published by the U.S. State Department have moved forward in most categories over the months of the Trump administration—but while this could indicate processing it could also simply indicate a lack of demand.

The second reason is that the system is in danger of losing what little transparency it has. USCIS has not updated its “Historical Processing Times” document since March. This tool has been one of very few ways that Americans and immigrants can track the activities of the government and learn how long it is taking to process applications—in short, where the government is allocating its resources.

There are certainly indications that the Trump administration does not intend to allocate significant manpower toward operating our system of legal immigration. Not only have USCIS employees been asked to volunteer for 60-day details at ICE, but the agency has been forced to cut jobs—despite being almost entirely funded by user fees rather than appropriations from Congress. The cuts surprised officials within the agency, who pointed out, “We make money.” In April 2025, an unknown number of USCIS employees were sent an email telling them they could either resign or be fired at a future point. And while the Bureau of Consular Affairs at the U.S. State Department has not yet been targeted for widespread firings, plans have been circulated calling for the closure of embassies and consulates around the globe—which would increase wait times at nearby embassies and the consulates that remain open.

At the end of the day, however, processing times will not significantly increase—even if the resources available for them are cut—if demand also drops. In other words, if no one wants to come to the United States, no one will be delayed in coming. And in that regard, the experiences of current immigrants may send powerful signals to would-be immigrants of the future.

How are we treating the immigrants already here?

For decades, until President Trump’s first term in office, the consensus among both parties and all presidential administrations was that there was a bright line between “legal” and “illegal” immigration: illegal immigration was bad, but legal immigration was good. These lines weren’t quite as bright in policy as they were in rhetoric. The executive branch often used its discretion to grant some form of legal protection to undocumented immigrants; much more infrequently, it exercised its authority to revoke individuals’ permission to remain in the U.S. But the distinction between having papers and lacking them was generally respected and upheld.

In President Trump’s first term, his administration argued that some legal immigrants were also undesirable, and pushed policies to restrict incoming legal immigration. It also attempted to strip discretionary protections from large groups of immigrants—including the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program and several nationalities’ grants of Temporary Protected Status (TPS)—but was generally stymied in court.

With its return to office, the administration has picked up where it left off—and then some. It has resumed the large-scale revocation of protections such as TPS and humanitarian parole. Furthermore, it has attempted to delete the compliance records of several thousand international students studying here, confusing them and their schools about their legal status, while seeking to prevent some universities from enrolling international students at all.

The message of these operations, and of widely-reported efforts to use government data (such as tax returns and Social Security records) for immigration enforcement, sends a message that all immigrants are receiving regardless of legal status: any information that has ever been given to the government can be used against them, and any interaction with the government could turn into an arrest.

Meanwhile, the immigrants who have no federal records, because they have never had legal status and never been apprehended, are now at risk of being prosecuted as federal criminals for the crime of failing to register their existence with the government—in other words, failing to turn over information that could be used to deport them.

The ripple effects of the effort to make immigrants’ lives as precarious as possible—to strip them of the ability to work legally, to participate in the life of their communities without fear, to travel internationally or even take a domestic flight—cannot be fully understood within six months. The administration is stripping (or attempting to strip) work permits from people who are essential to the U.S. workforce, while making it harder for employers to recruit talent from abroad. What is happening to universities around the country, where harassment of students and researchers is leading to concerns about continued international student enrollment, should serve as an early warning to employers in other sectors of the American economy.

Stripping them of legal status and protections

Not all immigrants who have the ability to work legally in the United States, or who are not presumed deportable, are equally protected—or, for that matter, equally “legal.” The gradations are so fine that, for example, whether someone is eligible for a driver’s license in several states depends on whether they have “lawful status” in the United States, or merely “lawful presence” here.

U.S. law gives the federal government the authority, in certain circumstances, to revoke the status of anyone who wasn’t granted citizenship at birth—up to and including naturalized citizens. But the law requires the government to follow certain steps to do it—and affords immigrants more opportunity to contest the revocation—depending on what form of legal status or protection they have. Naturalized citizens, for example, must be “denaturalized” in a lengthy and resource-intensive federal court proceeding, then brought to immigration court to revoke their green cards as well. The grounds for denaturalization are also very limited, meaning most naturalized citizens cannot have their status revoked (which is why the Trump administration’s much-touted denaturalization campaign during its first term achieved limited results).

Both the reasons for revoking protections and the process that must be followed vary. However, in general, there are two axes on which the second Trump administration has worked to make immigrants’ status more precarious:

- Wholesale revocation for entire groups and categories of people—something that can only be done for certain lesser forms of legal protection which have been granted by the executive branch to begin with, and which even then must follow legally-specified procedures; and

- Revocation of individual visas and statuses based on (theoretically) individualized grounds.

The first of these is a continuation of a policy pursued under Trump’s first term—but which now has the potential to affect many more people, thanks to the Biden administration’s aggressive use of temporary protections. The second is a much more aggressive posture than the first Trump administration took.

Targeting the newly-expanded population of “twilight” immigrants for mass revocation of legal protection

Since the Obama administration, the executive branch’s power to grant temporary protections from deportation (and work permits) to groups of immigrants without full legal status—or to revoke those protections—has become a hotly debated tool of immigration policy. There are several legal authorities that presidents have used to extend these protections, including deferred action (which the Obama administration used successfully to create the DACA program, but was stopped by the Supreme Court when it attempted to extend protections to parents of U.S. citizens) and humanitarian parole, used aggressively by the Biden administration. It also includes Temporary Protected Status (TPS)—which had been used by presidents of both parties since its creation in 1990, but which the first Trump administration attempted to curb. (The first Trump administration’s attempts to sunset TPS for particular countries were stopped by federal courts or delayed until they were formally undone by the Biden administration.)

Often, discretionary protections can offer some form of stability to people who are already in the United States but lack any way of “getting in line” for full legal status. However, parole, in particular, can also be used to allow people to enter the United States who would not otherwise be able to do so legally. The Biden administration was very active in doing both. It used parole to create “alternative legal pathways” for nearly 1.7 million people to enter the United States legally, while also using TPS to cover hundreds of thousands of people who were here (including some of those who had been paroled in by the administration to begin with). As a result, many more people were in the United States on “twilight statuses” when Trump reentered office than when he left.

To the Biden administration, these protections served as an alternative to undocumented migration—by allowing people to come safely and stay on the books with the government while living in the United States. However, to the Trump administration, they were seen as a backdoor way to expand illegitimate migration. On the campaign trail, Trump and Vice President J.D. Vance attacked Haitian immigrants in Springfield, Ohio, as “illegal,” despite the fact that most of them were protected by parole and/or Temporary Protected Status. When the fact that they were in fact legal was pointed out to Vance, he insisted that “If Kamala Harris waves the wand illegally and says these people are now here legally, I’m still going to call them an illegal alien.”

And so the Trump administration has shaped reality to fit its worldview, taking over a million people who had done everything the “right way” —from finding sponsors in the U.S. under the Cuban, Haitian, Nicaraguan and Venezuelan (CHNV) parole program to waiting in Mexico for months with a CBP One appointment, to applying for and sometimes renewing TPS—and making them “illegal.” As a result of these actions—which have affected far more people than the Trump administration has been able to deport—the number of people in the U.S. without any legal status has almost certainly increased since January 2025.

Major Expansions of “Twilight Status” Under the Biden Administration

Uniting for Ukraine

Description: A program using humanitarian parole to bring Ukrainians fleeing Russia’s 2022 invasion to the United States while the war is ongoing.

Number of beneficiaries (estimated): At least 187,000

Current status: Ukrainians retain their temporary protections under this program, despite intermittent reports that the Trump administration wants to rescind them.

Humanitarian parole for Afghans

Description: A program granting two-year parole grants to Afghans after the U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan in 2021, including those brought to the U.S. under Operation Allies Welcome.

Number of beneficiaries (estimated): 76,000

Current status: Afghans retain their temporary protections under this program, despite intermittent reports that the Trump administration wants to rescind them.

The Cuban, Haitian, Nicaraguan and Venezuelan (CHNV) parole program

Description: The CHNV program granted two years of protections and work eligibility to up to 30,000 people from Cuba, Haiti, Nicaragua and Venezuela each month, starting in early 2023 (expanding an earlier parole program for Venezuelans which started in fall 2022.)

Number of beneficiaries (estimated): 532,100 total, many of whom later became eligible for Temporary Protected Status or other adjustment

Current status: The Trump administration stopped granting parole for new beneficiaries at the beginning of its second term in office. In April 2025, the Department of Homeland Security announced that current parolees would be prematurely stripped of their parole. While that decision was temporarily delayed by a federal judge, it has since been allowed to go into effect. On June 12, DHS announced it was sending notifications of parole revocation to CHNV beneficiaries.

CBP One parole

Description: Parole for asylum-seekers who came to the U.S. by making appointments on the CBP One app to present themselves at ports of entry, which allowed them to work legally in the U.S. while waiting for their hearings in immigration court

Number of beneficiaries: 936,500, many of whom were subsequently granted asylum or other forms of legal status, or had their parole revoked after losing their cases

Current status: In April 2025, the Trump administration sent mass notifications to CBP One parolees that they would lose their parole within seven days; this mass revocation of parole under CBP One has been challenged in court.

Temporary Protected Status designations

Number of beneficiaries: 505,400 as of September 2024

Description: Haiti, August 2024

Number of beneficiaries (estimated): 523,000, including 319,000 newly-eligible recent arrivals

Current status: The Trump administration advanced the expiration date for Venezuelans designated for TPS in 2021 to September 2025. On February 6, 2025, the administration announced its intent to revoke the extension of TPS for those who arrived later and were designated for it in 2023. This revocation was temporarily enjoined by court order, but the U.S. Supreme Court allowed it to go into effect for all Venezuelans who had not already been approved for TPS on February 5.

Description: Ukraine, August 2023

Number of beneficiaries (estimated): 63,425 as of September 2024

Current status: Valid until October 2026

While the federal government has the power to revoke these protections, it is still obligated to follow the appropriate process. The Trump administration’s aggression and haste, however, have arguably pushed it to violate that process. The Department of Homeland Security attempted to claw back decisions already issued by the Biden administration to extend TPS for Venezuela and Haiti for 18 months—resulting in a lawsuit that remains in federal court. It announced via a press release that it would terminate TPS for Afghanistan and Cameroon—then did not issue a Federal Register notice confirming the decision, as required by law, for another six weeks. Only on May 13—a week before Afghans’ existing TPS grants were said to expire—did the administration announce in the Federal Register that the country would lose its designation in 60 days.

Stripping these protections—and the work permits associated with them—has a tremendous impact on the U.S. workforce. According to estimates from FWD.us, the Trump administration’s terminations (or attempted terminations) of TPS would affect over 200,000 workers—and over 150,000 more are in danger of losing their work permits faster than expected, thanks to the administration’s reversal of the Biden administration’s extension for Venezuela (under the 2021 designation). Indeed, the Trump administration’s attitude toward TPS raises the possibility that all current TPS holders will lose their protections over the next two years—cutting a total of 570,000 workers out of the legal workforce. People who entered the U.S. on humanitarian parole under the Biden administration, meanwhile, account for 740,000 U.S. workers—including approximately 120,000 in the construction industry, and 120,000 in leisure and hospitality.

People who have lost temporary protections under Trump face a choice to remain in the U.S. without papers and risk deportation, or to leave proactively. Unsurprisingly, some are taking the latter option even while they still have deportation protections, out of fear. “Everybody is afraid,” Venezuelan activist Adelys Ferro told Politico about TPS holders. Virginia music teacher Jesus Rodriguez left his elementary-school students in April, departing the U.S. for Spain while his humanitarian parole was still valid. He told the Washington Post that he was afraid of being detained or deported, despite his protections; “I don’t want to show my daughter something terrible like that.”

Terminating student visas based on free speech and traffic tickets—and panicking students by deleting thousands of records

In keeping with its broader attacks on American colleges and universities, the Trump administration has shown particular interest in foreign students, including graduate students, many of whom are also scientific researchers.

Students who have been active in campus protests opposing Israel’s war in Gaza have been individually targeted for visa revocation and status termination, arrest and detention—often without any notice. Tufts graduate student Rümeysa Öztürk was arrested on the street by masked men in plainclothes in March 2025. She later learned her status had been revoked days earlier, on the grounds that her continued presence in the United States “might undermine U.S. foreign policy” by making Jewish students on her campus feel unsafe and “indicating support for a designated terrorist organization”; the only evidence that the Trump administration has offered to support this claim is an op-ed she co-authored in the Tufts student paper in 2024, urging the university to support student senate resolutions to recognize the war in Gaza as a genocide and divest from the government of Israel. Öztürk was detained for several weeks, suffering several asthma attacks, before being ordered released by a federal judge while her deportation case proceeds.

While cases like Öztürk’s—which have also resulted in the federal government attempting to revoke the permanent residency of at least two green-card holders, using the same “foreign policy” grounds—have been highly visible, many more students have been made vulnerable through a different Trump administration effort: deleting thousands of students’ records in the Student Exchange and Visitor Information System (SEVIS), which universities and the government use to ensure that students remain legally enrolled. In April, the Trump administration canceled about 4,700 students’ SEVIS records, triggering notices to their schools. The cancelations were based on a database check with the National Crime Information Center, which tracks interactions with law enforcement—including traffic tickets and dismissed charges. (Akshar Patel’s record was canceled weeks before his graduation, based on a charge for reckless driving that had been tossed out of court.)

Some students had their immigration status stripped based on the criminal check, but DHS also deleted untold numbers of SEVIS records for students who retained their legal status in the U.S. All the cancelations, however, showed up for school officials as “identified in criminal records check and/or has had their visa revoked”—leading many schools to tell students that they had lost permission to continue their studies.

This miscommunication was not only chaotic, but actively harmful. Any student who left school, missed classes, or quit on-campus jobs violated the terms of their immigration status by doing so. Thus, by trying to comply with university notifications based on the SEVIS cancellation, students who had not lost valid status put themselves at risk of losing it.

Facing more than 100 lawsuits from students, the Trump administration agreed to restore the individual SEVIS records. However, ICE has made it clear that it is now a matter of policy to cancel the SEVIS record of any student once the State Department orders a visa revoked—rather than allowing them to complete their studies before leaving the U.S. This policy further encourages the State Department to engage in immigration enforcement, rather than simply adjudicating petitions to enter the U.S.

Instead of communicating these changes with students and universities in a proactive and orderly fashion, the administration has ambushed students on campus or told them their visas were no longer valid when they attempted to enter the United States. The memo revoking Rümeysa Öztürk’s visa specifically instructed that “due to ongoing ICE operational security […] the Department of State will not notify the subject of the revocation.” These tactics make it harder for students who lose their status to comply with the law, while increasing the chances that they will be ordered removed and barred from legally reentering the United States. Even when students are notified of their change in status before being detained by ICE, the prospect of detention may lead them to voluntarily leave the U.S., like Columbia graduate student Ranjani Srivanasan, rather than fight their cases.

Axel, a DACA recipient trying to protect his community

Since President Trump’s election, Axel Herrera has seen a growing number of local police traffic checkpoints popping up across his North Carolina community. As a DACA recipient, Axel has legal protection from deportation, but some of his friends and family members have already been detained or deported following random traffic stops, and many undocumented members of his community now live in constant fear. “It’s creating a hostile environment,” Axel says. “It’s pretty clear what the government is trying to do.”

Axel is 27. He has lived here since age seven, after his family left Honduras in search of a better life. When Axel received DACA status, he felt he’d finally achieved his family’s dream. He won a scholarship to Duke University, became the first in his family to attend college and graduated with multiple awards and a prestigious Congressional internship.

He went on to become North Carolina’s civic engagement director for Mi Familia en Acción, a nonprofit group supporting Hispanic communities. He’s spent the past few years registering citizens to vote, creating youth programs, and mentoring immigrants as they seek educational and professional opportunities. “All I ever wanted was to belong, and to give something back,” he says.

But the new political reality has been a blow. Ongoing challenges to DACA’s legality could jeopardize Axel’s protection from deportation. Axel has to renew his DACA status and employment authorization every two years—and while he rushed to process his paperwork just before Trump took office, he has no way of knowing if that will still be possible when his current status expires in 2026. He knows that some Dreamers are now struggling to get their papers processed, and the Trump administration has already deported at least one DACA holder after claiming they had an outstanding deportation order. “Right now, everything is up in the air,” Axel says. “I’m very concerned about the future.”

One possibility is that courts could leave DACA in place, but revoke DACA recipients’ right to work. Because of that uncertainty, Axel is walking away from his hard-won job and returning to school. This fall, he’ll leave North Carolina for Yale, where he’s won a scholarship to study business and public policy. “It’s a great opportunity, but also a hedge against losing my status,” he explains. “If I lose my work authorization, then being a student might buy me some time and let me find a different path forward.”

He feels torn about leaving his community behind. Everyone he knows is constantly on WhatsApp, assessing police conditions anytime they leave the house. He knows many young Venezuelans whose humanitarian parole was recently revoked, leaving them unable to work or study. Over the past 6 months he’s also seen families torn apart by raids and deportations, or who are simply too afraid of ICE to go to school. “I speak all the time with young people whose whole future is on the chopping block,” Axel says.

But despite Axel’s current protections, “there’s this looming sense that things could get worse fast,” he says. Under Trump, anti-immigrant sentiment and policy has become more entrenched. He’s especially worried about the long-term impact of a new state law requiring sheriffs to cooperate with ICE. And he fears for his and his family’s future. “After 20 years, we’re barely scratching the surface of dealing with our status issues,” he says. “It never ends—and the Trump administration is rolling back so much of the progress we’ve made.”

Erecting procedural barriers and blockades for people trying to obtain more permanent legal status, or to maintain their work permits

Noncitizens in the United States don’t just apply for status once. They have to constantly remain “in status,” renewing green cards, visas, work permits, and grants of deferred action, TPS or parole. They have to resubmit biometrics for fingerprints that haven’t changed and retinal scans the government already has on file. And of course, each time, they have to pay a fee.

Obtaining more permanent status—a green card, for those who are eligible to adjust to one, or citizenship for those who already have green cards—is more rigorous still. But the reward for submitting to these interviews and security checks is greater stability, since these are less subject to government discretion than visas or discretionary protections are.

The Trump administration has simply pushed people off this path to citizenship. It has stopped processing applications, including green card applications, for groups of immigrants it deems unworthy, including refugees, asylees, and beneficiaries of parole programs. It seeks to reduce the amount of time that a work permit is valid for, increasing the risk that work permits will lapse while stuck in backlogs, and to impose inordinately expensive fees for each renewal and application.

In the long run, this will further erode the authorized immigrant population while pushing more people into the shadows. It may also have unwelcome economic impacts, especially among employers who have found recent success by tapping into the immigrant labor market.

Blockading green cards and other applications for refugees, asylees, and parolees

In the past, the government has encouraged those who are eligible for permanent status and (especially) U.S. citizenship to obtain it. The Trump administration, however, has compounded its efforts to erode protections for refugees, asylum-seekers, and parolees by making it impossible for them to obtain more permanent status.

In February 2025, Acting United States Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) Deputy Director Andrew Davidson sent a memorandum to USCIS adjudicators ordering them to pause processing on all applications for immigration benefits filed by people who had come to the U.S. as beneficiaries of the CHNV and Uniting for Ukraine programs, preventing them from converting their temporary protections into something more permanent.

Furthermore, the memo required USCIS to stop processing applications for anyone who had benefited from Family Reunification Parole (FRP) programs. Under FRP, people who already had pending applications for legal status with USCIS, but who had not been able to come to the United States due to visa backlogs, would be allowed to reunite with their U.S.-resident relatives while waiting for their turn in line. By freezing the processing of these applications, the memo essentially put these families in a worse position than they had been to begin with—sacrificing their ability to obtain green cards and citizenship because they had chosen previously to wait inside the United States.

Because this freeze also applies to work permit renewals, the memo also further erodes the ability of people living in the United States to work legally here, and pushes them out of the workforce. One Ukrainian woman interviewed by National Public Radio (NPR) had been working three jobs in the restaurant sector before losing her work permit. “My hands are shaking because I have no work,” she told NPR.

While the application freeze was supposed to be temporary in order to review vetting practices, it remains in effect and the Trump administration has given no indications as to when it will resume. A lawsuit has been filed and is still pending.