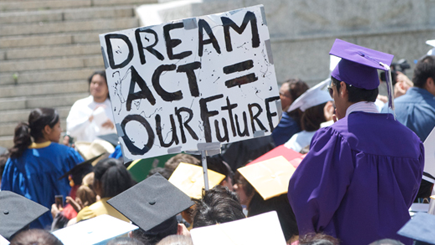

Each year, approximately 65,000 undocumented students graduate from American high schools. While many hope to pursue higher education, join the military, or enter the workforce, their lack of legal status places those dreams in jeopardy and exposes them to deportation. Over the last decade, there has been growing bipartisan consensus that Congress should provide legal immigration status for young adults who came to the country as children and graduated from American high schools.

Since 2001, when the Development, Relief, and Education for Alien Minors (DREAM) Act was first introduced as bipartisan legislation, its main provision—providing permanent resident status (i.e. a “green card”) upon completion of two years of college or service in the military—has held out hopes of a lasting solution for these young people. As the current political environment has become more polarized, bipartisan support for the DREAM Act has waned. Recently, however, more narrow proposals have circulated that either restrict eligibility for permanent residency to a smaller group of young people or offer no dedicated path to permanent residency (and, eventually, U.S. citizenship).

In recent months, much attention has been focused on an as yet undisclosed proposal from Sen. Marco Rubio (R-FL) that would reportedly offer temporary legal status for undocumented high-school graduates but no dedicated path to permanent residency. In January 2012, Rep. David Rivera (R-FL) introduced the ARMS Act, which would require military service as a condition for obtaining permanent resident status. In May 2012, Rep. Rivera also introduced the STARS Act, which would permit undocumented students to become permanent residents if they complete a four-year degree, provided that they were generally under the age of 19 at the time of application.

This fact sheet explores the differences between these various proposals, focusing on the implications of a direct path to permanent residency. In particular, we examine the assumption that the regular immigration system offers a solution for undocumented youth.

What Distinguishes the DREAM Act from Alternative Proposals?

The DREAM Act (S. 952, H.R. 1842) provides “conditional” permanent residency to qualified unauthorized immigrants who enrolled in college or serve in the military. After meeting a set of requirements, including completion of at least two years of college or military service, the conditional status could be converted to full-fledged permanent resident status, which is a prerequisite for obtaining U.S. citizenship. The legislation currently before the Senate and the House would permit individuals up to age 35 to benefit from the DREAM Act, provided that they entered the United States before their 16th birthday and resided in the country for at least five years before the bill’s enactment. The two-year college or military requirement could be met in a variety of ways, including attending community or vocational school or service in the National Guard. Upon completion of the two-year requirement, applicants could seek to remove the condition and become permanent residents.

In contrast, the ARMS and STARS proposals would focus on a much smaller group of individuals. The ARMS legislation, for instance, permits applicants under the age of 30 to apply for conditional nonimmigrant status, provided that they enroll in military service within nine months of receiving that status. The nonimmigrant status lasts for five years and may be renewed for another five years if the recipient has completed at least two years of active duty military service or four years of reserve duty. During the five year extension, beneficiaries may have their status adjusted to that of a permanent resident. Meanwhile, the STARS proposal limits eligibility to individuals who are 19 or younger at the time they apply (or 21 if under an order of voluntary departure received before the age of 19). The nonimmigrant status lasts for five years and may be renewed for an additional five-year period if the applicant graduates from a four-year college or university. Three years after the five-year extension is granted, the beneficiary may have their status adjusted to that of a permanent resident.

Meanwhile, public statements issued by Sen. Rubio and his staff about his proposal suggest that undocumented students would also receive temporary nonimmigrant status while in college or the military. However, unlike the other legislation discussed, Sen. Rubio’s proposal would reportedly offer no dedicated pathway for moving from temporary to permanent resident status. Instead, Sen. Rubio has said that individuals could only qualify for permanent resident status—which is a prerequisite for obtaining U.S. citizenship—if they would otherwise be eligible for a green card.

What is the Difference Between “Nonimmigrant” and “Conditional” Permanent Resident Status? Between “Nonimmigrant” and “Permanent Resident” Status?

Noncitizens who are authorized to enter or remain in the United States are often colloquially referred to as having “legal status,” but that phrase does not fully convey the nuances of immigration law. Broadly speaking, immigration law divides individuals into “immigrants” and “nonimmigrants.” Most nonimmigrants are foreign nationals who come to the United States for a limited period of time and do not intend to stay permanently. For example, tourists, students, journalists, and performers from overseas arrive in the United States on nonimmigrant visas. An “immigrant” (or permanent resident or “green card” holder) is a foreign national who intends to remain in the United States indefinitely. Unlike nonimmigrants, foreign nationals with permanent resident status are permitted to work in the United States without condition. Obtaining permanent resident status is a prerequisite to becoming a U.S. citizen.

In between the definition of nonimmigrant and immigrant, however, lies a world of legal categories. Some nonimmigrants, such as tourists, are truly here for short-term visits, while others may be here in a temporary status due to violence or natural disaster in their home country. Many other nonimmigrants live and work in the United States for extended periods of time and may have the opportunity to apply for immigrant status from within the United States. Some nonimmigrant visas can be renewed indefinitely, while many others are limited to a finite number of years.

Some permanent residents are admitted on a “conditional” basis, most notably foreign spouses of U.S citizens. Conditional permanent residents have the same rights and obligations as other permanent residents but can lose their status by failing to meet certain conditions. For example, to minimize the possibility of marriage fraud, conditional permanent resident spouses of U.S. citizens must normally file a petition to have the conditions lifted about two years after being granted conditional permanent resident status. The DREAM Act follows the conditional model—applicants’ permanent resident status would be conditioned on completion of two years of college or military service.

Under the ARMS Act and the STARS Act, applicants would receive conditional nonimmigrant status while enrolled in college or the military. Following their graduation or completion of military service, applicants could then have their status adjusted to that of a permanent resident.

Because the meaning of “nonimmigrant” is not particularly clear, there has been significant speculation about the references to nonimmigrant status by Sen. Rubio. By historical standards, DREAMers are different from most nonimmigrants. They will not apply to come to the United States from their home countries. They generally have few ties to their home country, have little or no intention of moving back permanently, and have every hope and desire of becoming U.S. citizens. A status tailored to these unique circumstances would likely be significantly different from existing nonimmigrant categories. Unless the law is properly drafted and coordinated with existing laws, it could become significantly difficult to leverage nonimmigrant status into the fairly narrow opportunities for adjusting to permanent resident status under current law.

Under the Existing Immigration System, How Can Noncitizens Become Permanent Residents?

Without a dedicated path to permanent residency, significant uncertainty remains about whether and how qualified applicants will be able to obtain green cards under the Rubio proposal. As we have previously explained, the pathways to becoming a permanent resident in the United States are limited. Most people who receive permanent resident status qualify on the basis of a pre-existing family or employment relationship, and that system is constrained both by the supply of visas and cumbersome regulations governing their distribution.

For example, the number of immigrant visas available in both family and employment-based categories has not changed since 1990, causing significant backlogs for many applicants. Only 140,000 employment-based immigrant visas are available per year, and eligibility for such green cards is highly dependent on the applicant’s type of degree and profession. For example, someone who receives a degree in elementary education and has a job offer would not necessarily qualify for an employment-based visa. Meanwhile, someone who receives a degree in engineering might qualify but find that there are no visas available. The limited number of employment-based visas available makes it extremely difficult to predict who might obtain employment through the process as it operates today.

Federal law also places limits on the number of immigrant visas that can be given to nationals of any particular country. Thus, no matter how many qualified applicants exist from countries like Mexico, India, China, and the Philippines, only a small percentage can obtain a green card in any given year.

Unless a dedicated pathway to permanent residency is provided, formerly undocumented young people who qualify for permanent residency through an employer or a close family member would increase the demand for green cards and likely extend backlogs even further. Historically, most special legalization programs—such as the DREAM Act—exempt beneficiaries from existing visa caps precisely to avoid these problems. According to statements made by Sen. Rubio, undocumented young people who are eligible for permanent residency would have to compete for the small number of green cards available. Such an approach could put more pressure on an already overburdened system.

What is the Downside to Temporary Immigration Status?

Because of the intricacies of immigration law, it can be complicated and sometimes difficult to maintain eligibility for and obtain a green card. Even if given the option of repeatedly renewing their temporary status, potential beneficiaries would face the complications and costs of constant renewals, the uncertainty of a status that has no real protections for remaining in the United States, and the possibility that career advancement and other opportunities would be out of reach because they lack permanent resident status.

For example, temporary employment visas, such as the H-1B visa for high-skilled workers, eventually expire. If an employer wants to retain an employee, the employer can choose to petition for an employment-based green card, and the employee is dependent on that employer to complete the process. In addition to the backlog, the process for obtaining an employment-based green card can be complex. There can sometimes be gaps in employment or renewal of employment authorization that put legal status in question. Employees with temporary status may not be able to accept promotions or change employers because their status is attached to their current job. The problems with the current employment visa system have led many talented immigrants to abandon their green card applications or simply go to other countries that are more welcoming.

Because the only unlimited or “uncapped” number of green cards is for immediate relatives of U.S. citizens, marrying an American could easily become the default path to permanent residency for DREAMers unless the Rubio plan offers an exemption from existing restrictions or other appropriate safeguards. It is unlikely that policymakers want to encourage DREAMers to marry U.S. citizens just to remain in the country.

Do Temporary Residents Have to Leave the United States to Obtain Permanent Residency?

Under existing law, noncitizens who enter the country without permission—as many undocumented youth did as children—generally cannot become permanent residents from within the United States. Instead, they must leave the country and apply for permanent residency from a foreign consulate. Complicating matters, existing law also imposes a three- to ten-year bar on return to the United States for noncitizens who have been unlawfully present in the United States for more than six months after their 18th birthday—creating a Catch-22 whereby DREAMers who entered illegally would become ineligible for a green card as soon as they left the country to apply for permanent residency. Additional time, expense, and applications are necessary to address this bar, and there is no certainty that it could be lifted.

Why is a Direct Path to Permanent Residency Better Policy?

For many undocumented high-school graduates, a temporary nonimmigrant status is not a permanent solution as there is no guarantee they could ultimately qualify for a green card. In the event that legislation was enacted that only provided for a temporary nonimmigrant status, there is no doubt that some individuals—with the right mix of qualifications, family or employment ties, and patience—would be able to access the current system. The variables are so numerous, however, and the barriers so high, that the lack of a dedicated path to lawful permanent status would add to the complexity and uncertainty of our already overburdened immigration process. Even some who eventually qualify for a green card, such as those who entered illegally, run the risk of being barred from the country if they must leave the United States to apply, as is required under current law.

If the objective of proposals aimed at providing help to undocumented youth is to allow undocumented high-school graduates to remain in the United States permanently, the best way to achieve that is to create a dedicated path to permanent residency. In fact, there is an entire category of “special immigrants” that covers groups who receive a temporary status that can be converted to permanent residency—including religious workers, abandoned children, victims of trafficking and other crimes, and Afghan and Iraqi nationals who worked for the U.S. government. These dedicated paths take into account unique circumstances and eligibility issues, create clear benchmarks for moving on to the next step in the process, and do not compete with the already overburdened immigrant visa system currently in place.

Conclusion

There is already broad recognition that young people who were brought to the United States at a young age by their parents should not be penalized for their lack of immigration status. They have been raised and educated here, and are “American” in nearly every sense of the word. There is a growing consensus that they deserve permanent status. In the debate over how to achieve that result, legislators should craft legislation that takes into account the current problems with the existing immigration scheme, avoiding unnecessary delays and complications. In the long run, any solution for undocumented youth must squarely address the challenges posed both by the unique circumstances of this population and the highly complex immigration system in which a new law must operate.