On June 6, 2013, the House Judiciary Committee considered H.R. 2278, the “Strengthen and Fortify Enforcement Act,” commonly known as the SAFE Act. This wide-ranging immigration enforcement bill would make unlawful presence in the United States a criminal act punishable with jail time, greatly expand detention of immigrants, authorize states and local governments to create their own immigration enforcement laws, and impose harsher penalties and restrictions for immigration violations, among other enforcement-related provisions. The bill, introduced by Judiciary Chairman Bob Goodlatte (R-VA) and Immigration Subcommittee Chairman Trey Gowdy (R-SC), was the subject of a contentious committee mark up, ending in its passage out of committee on a straight party line vote of 20 to 15. The SAFE Act is one of several bills that the House leadership might offer as part of its “step-by-step” approach to immigration reform, in which various House bills addressing different aspects of the immigration system may be voted on separately.

However, the SAFE Act represents an attrition-through-enforcement approach to unauthorized immigration that has not proven effective and which runs contrary to many of the objectives of immigration reform. It returns to a philosophy which holds that punitive enforcement measures alone can address the many flaws in our immigration system. But the United States has essentially been pursuing an enforcement-only approach for decades which has divided communities and proven to be extremely expensive, all without actually achieving its goals. It is important to keep in mind that, since 1986, the federal government has spent $187 billion on immigration enforcement, yet the unauthorized population has tripled in size to 11 million during that time. The House Judiciary’s endorsement of an outdated philosophy that touts more enforcement, more detention, more penalties, and a more complicated, expensive, and decentralized immigration enforcement system flies in the face of the House leadership’s repeated pledge to fix that very system.

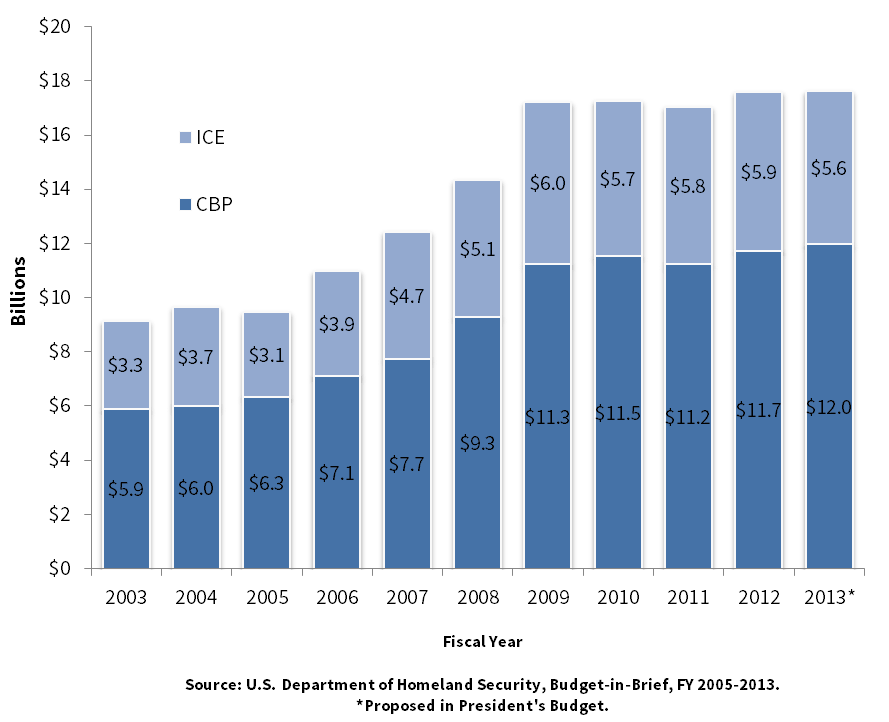

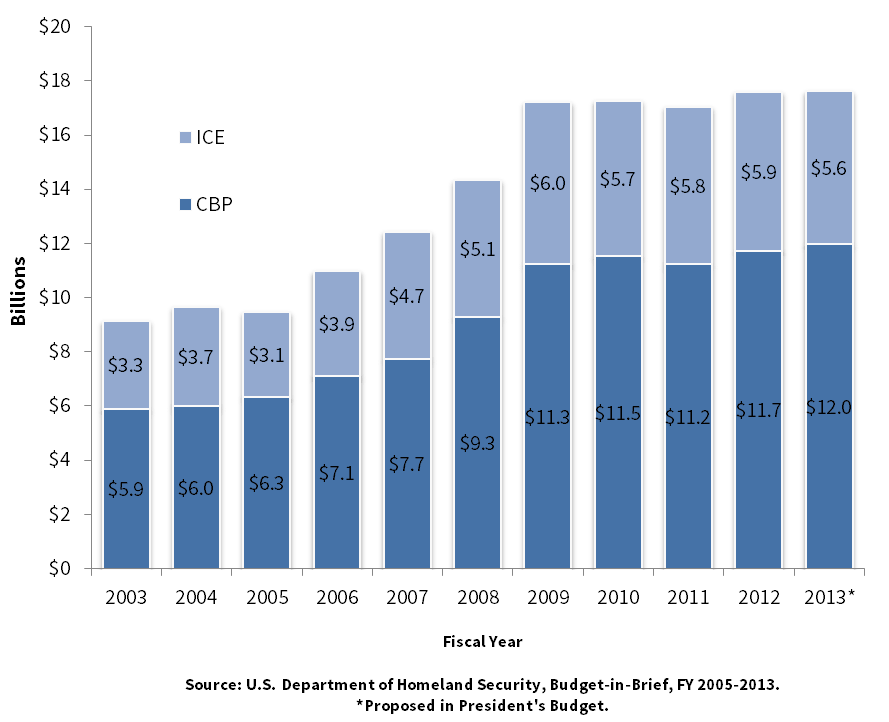

Spending on immigration enforcement is at an all-time high

Contrary to the impression created by supporters of the SAFE Act, federal spending on border and immigration enforcement has been growing for years and is now at an all-time high. Since the creation of the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) in 2003, the budget of U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP)—the parent agency of the Border Patrol within DHS—has increased from $5.9 billion to $12 billion per year. On top of that, spending on U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), the interior-enforcement counterpart to CBP within DHS, has grown from $3.3 billion since its inception to $5.6 billion today {Figure 1}.

Figure 1: CBP & ICE Annual Budgets, FY 2003-2013

This growth in enforcement spending has been accompanied by a rise in the number of enforcement personnel. In fact, the number of border and interior enforcement personnel now stands at more than 49,000. The number of Border Patrol agents doubled from 10,717 in FY 2003 to 21,394 in FY 2012. The number of CBP officers staffing ports of entry (POEs) grew from 17,279 in FY 2003 to 21,423 in FY 2012. And the number of ICE agents devoted to Enforcement and Removal Operations increased from 2,710 in FY 2003 to 6,338 in FY 2012 {Figure 2}.

Figure 2: CBP Officers, Border Patrol Agents, and ICE Agents, FY 2003-2012

What are the origins of the SAFE Act?

The SAFE Act is a direct descendant of H.R. 4437, the Border Protection, Antiterrorism, and Illegal Immigration Control Act. This bill was passed by the House in 2005 and is commonly known as the Sensenbrenner bill, named for the former Chair of the House Immigration Subcommittee. When the Sensenbrenner bill passed the House it led to mass public demonstrations because it criminalized unauthorized immigrants, expanded detention, and created additional harsh immigration penalties. The SAFE Act revives these provisions, but goes further. Significant provisions of the SAFE Act attempt to overturn last year’s ruling by the Supreme Court in Arizona v. U.S. that limited states’ ability to enact their own immigration laws because immigration is the domain of federal law. Since that decision, a series of other cases interpreting this ruling have struck down state immigration laws on a range of issues, such as forbidding landlords from renting to unauthorized immigrants and precluding the enforcement of contracts with them. The SAFE Act would essentially resurrect all these laws and encourage the passage of more because it changes federal law to comport with SB 1070 and similar local attrition-through-enforcement bills.

How would the SAFE Act affect the enforcement of immigration laws?

The breadth of the provisions in the SAFE Act, allowing for unlimited state and local enforcement of federal immigration law as well as an expansion of state and local immigration laws, amounts to an abandonment of federal control of immigration enforcement and creates a patchwork of potentially conflicting, burdensome, inefficient, and divisive laws. In fact, some provisions of the SAFE Act explicitly require the federal government to renew federal-state enforcement models that the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) has rejected as inefficient and prone to discrimination and racial profiling—essentially opening the door to abuses of the system such as those that have been uncovered during Sheriff Joe Arpaio’s tenure in Maricopa County. The negative social and economic consequences of state immigration enforcement laws have been well-documented and have proven highly divisive, so much so that the Supreme Court, in its opinion in Arizona v. U.S., urged Congress to face its responsibilities and pass a coordinated and unified federal enforcement scheme. Instead, the SAFE Act would have the federal government cede ground to the states, encouraging the creation of a patchwork of hundreds of immigration laws at state and local levels. The resulting proliferation of state and local immigration laws similar to Arizona’s, enforced by untrained local authorities, would create a complicated, expensive, and conflicting patchwork of regulation, harming the ability of local law enforcement to prioritize the prosecution of violent crimes and causing economic harm and legal uncertainty for local businesses. Arizona and Georgia serve as case studies in how a state which chooses to implement its own punitive immigration law can rapidly incur hundreds of millions of dollars in economic losses as a result.

The SAFE Act would also transform the act of being in the country unlawfully into a criminal offense, shifting the enforcement of immigration law from a civil framework in which deportation is the ultimate penalty to a criminal one in which a possible prison term (followed by deportation) is the norm. Expanded criminalization at the federal level, expanded state and local enforcement, and a massive increase in federal detention are all contemplated by the SAFE Act, at a time when public sentiment supports legalizing rather than deporting or criminalizing the unauthorized population. This massive increase of criminalization, detention, and deportation of immigrants would also be extraordinarily expensive and divert law enforcement priorities and resources from fighting violent and serious crime. DHS already spends $2 billion a year on immigration detention alone, or $5.05 million per day. Ironically, the SAFE Act, if enacted, would further expand the kind of punitive measures that have been shown to undermine local economies and a functional immigration system.

What are the consequences of expanded state and local enforcement of immigration laws?

Under current law and policy, federal, state, and local governments have numerous cooperative relationships that exist to facilitate enforcement of immigration laws. Many of these programs have come under fire, most notably the 287(g) program, for undermining public safety, shifting local emphasis from community policing to immigration enforcement, and creating an atmosphere that encourages racial profiling. While the federal government has rejected many of these charges in programs such as Secure Communities, it has significantly revised the 287(g) program, terminating the contracts of notorious violators like Maricopa County, revising the terms of the agreements entered into with localities, and restructuring the program. Under the SAFE Act, these reforms would be eliminated, and the decision as to whether to enforce immigration laws would be controlled by state and local jurisdictions.

Law enforcement and community groups have been frequent critics of unregulated state and local enforcement of federal immigration laws, pointing out that such programs are costly, reduce levels of trust between the public and law enforcement, turn police officers into immigration agents, and—in the wrong hands—are vehicles for discrimination and racial profiling. Given this critique, expansion of 287(g)-type programs and the elimination of much federal oversight would heighten rather than improve the significant public safety concerns associated with state and local enforcement of immigration laws—especially because the SAFE Act requires the detention of all persons arrested on immigration violations at the state and local level. For these reasons, state immigration laws have become increasingly unpopular and local law enforcement officials are declining to serve federal immigration enforcement purposes. States are recognizing that punitive local immigration enforcement hurts local businesses and economies and causes the loss of jobs and tax revenue, in addition to dividing the local community and decreasing public trust in law enforcement.

What are the Key Provisions of the SAFE Act?

The SAFE Act redefines the federal enforcement landscape, moving immigrant prosecution from the civil to the criminal arena. The bill would create a system that promotes state and local enforcement of immigration laws and imposes expanded detention of unauthorized immigrants, harsher civil and criminal penalties for a range of immigration violations, expanded police authority for Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agents, and rigid limits on the authority of immigration agencies, prosecutors, and immigration judges to set immigration enforcement priorities. The following summary includes some of the most notable proposed changes to existing law, but is not exhaustive.

- Proliferation of State and Local Immigration Laws: Among the most controversial of the SAFE Act provisions are those which give state and local jurisdictions power to create and enforce immigration law. The Act would give them nearly unfettered authority to enforce federal immigration laws, excluding only the power to issue an immigration charging document and to actually remove unauthorized immigrants. In addition to enforcing federal laws, states and localities would be empowered to create their own immigration laws which penalize the same conduct as the federal law. This would allow state laws dealing with everything from the carrying of identity documents to working without authorization to residing unlawfully in the state. In practice, these kinds of laws, like Arizona’s SB 1070, are frequently struck down by the courts as conflicting with the federal government’s exclusive jurisdiction over immigration, as in the Supreme Court’s decision in Arizona v. United States. Moreover, in places where they have been put into effect, they have sometimes encouraged untrained local sheriffs and police to engage in racial profiling and other unlawful actions. Though the federal government would be required to create training materials for local law enforcement, local law enforcement would not actually be required take the training. The federal government might also be required to enter into controversial agreements known as 287(g) agreements, under which state and local police are deputized to act as federal immigration agents. It would be difficult for the immigration agency to refuse or terminate an agreement, absent compelling circumstances or being subject to court review. State and local officers would be granted immunity for actions undertaken in the course of enforcing immigration laws.

- Increased Detention: Among other changes to immigration detention, the SAFE Act would require federal authorities to take an unauthorized immigrant into custody within 48 hours of a state or local arrest, regardless of the individual circumstances. It would preclude the use of secure and less costly alternatives to detention, such as ankle bracelets or the release on bond of individuals who represent no flight risk or danger to the community, and would permit state and local jurisdictions to detain unauthorized immigrants for 14 days after completion of a sentence so that they may be taken into custody by DHS. The SAFE Act would also permit the unlimited detention of immigrants who have been ordered removed, but who cannot be repatriated—a practice found unconstitutional by the Supreme Court in Zadvydas v. Davis. Detention might also be required for immigrants who have been charged, but not convicted, of any crime. Increases in spending on detention would be authorized, including a requirement that the government spend sufficient sums to provide detention facilities for all unauthorized persons arrested by state and local jurisdictions. Such a large increase in immigration detention would be extremely expensive, as it currently costs $159 per day per detainee, or $5.05 million a day for all immigration detainees, many of whom have no criminal records or only committed traffic violations. States and localities would be required to cooperate and share information with federal immigration authorities, and those who fail to do so would be denied certain federal funding for community policing or other law enforcement or DHS grants.

- Increased Penalties for Immigration Violations. The SAFE Act would broaden the range of behaviors that are subject to immigration penalties and reduce the standard of evidence necessary to find someone inadmissible, removable, or ineligible for a benefit. In some cases, changes to the law would allow removal based on suspicion of criminal behavior rather than convictions. For example, a mere reasonable belief that someone may be or have been a member of a gang that was involved in crime would constitute grounds for removal. The use of expedited removal (deportation without access to court) would be expanded to include immigrants with most any type of criminal conviction that affects immigration status, irrespective of whether they were encountered at a port of entry or at the border.

- Expanded Definition of “Aggravated Felony.” H.R. 2278 would expand the definition of “aggravated felony,” an immigration term of art and the most serious offense in immigration law. If an offense is considered an “aggravated felony” (which may not necessarily be aggravated or a felony), it leads to automatic deportation and permanent banishment with no consideration of individual circumstances. Under the bill, the definition of aggravated felony would include expanded definitions of passport, visa, or immigration fraud; certain acts related to harboring of unauthorized immigrants; acts related to improper entry and reentry; and would include two convictions for driving while intoxicated, regardless of whether the convictions occurred long ago or were misdemeanor offenses. Someone detained based on one drunk driving arrest would also be subject to mandatory detention. This expanded list of aggravated felonies would make crimes as different as two DUI convictions, one conviction for shoplifting, or a conviction for premeditated murder all punishable by the maximum penalty under immigration law, further limiting the ability of authorities to focus resources on serious criminal offenders.

- Criminal Prosecution of Unlawful Presence: Under current law, illegal entry is a crime, but one that generally only applies if an individual is apprehended at the time of an illegal border crossing. Unlawful presence, by itself, is a civil—not a criminal—violation, and not punishable with jail time. The SAFE Act would change that, making every unauthorized immigrant into a criminal subject at any time to arrest, fines, and/or 6 months of jail time. This could include legal visa holders who overstay their visas by one day, such as a foreign executive whose flight home is delayed, or visa holders who violate the terms of their visas for technical reasons, such as student visa holders who fail to take full course loads. Subsequent offenders would be felons subject to fines and 2 years in prison.

- Increase in Heavily Armed ICE Agents: The SAFE Act would authorize 8,260 new positions within ICE, primarily for detention enforcement and deportation officers. It would expand arrest authority, provide body armor to all ICE agents and deportation officers, and make handguns, M-4 rifles and Tasers standard issue weapons. It also would create a new ICE Advisory Council designed to advise Congress on the impact of DHS policies on ICE officers.

- Reduced DHS Ability to Set Law Enforcement Priorities: The SAFE Act would prohibit implementation of ICE memos setting agency policy on prosecutorial discretion. These memos are the mechanism by which DHS sets national law enforcement priorities, including a focus on immigrants who have committed serious crimes over those who have no criminal records and those with compelling circumstances, such as close relatives serving in the military.

- Deportation of DREAMers: The SAFE Act would also eliminate DHS discretion to temporarily prevent the removal of DREAMers—unauthorized immigrants who were brought to the U.S. as children and meet certain educational and age requirements. Even those who have already been processed and granted temporary relief under the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program announced a year ago would become subject to deportation. The deportation of these law-abiding and educated young immigrants who are integrated into U.S. society could cost the economy hundreds of billions of dollars and damage the social fabric, in addition to being politically unpopular.

Does the SAFE Act belong in a coordinated immigration reform package?

Regardless of whether immigration reform is addressed through a comprehensive package, such as S.744, or a series of related bills, the ultimate result must reflect a coherent vision of immigration policy. Despite differences of opinion over what that policy might look like, the evidence supports expanded legal immigration, legalization of the unauthorized population, and the smart use of enforcement measures. The evidence does not support an indiscriminate increase in penalties, detention, and deportation that removes the ability of immigration authorities to make common-sense, fact-based decisions on individual cases. Furthermore, the economic and social harm caused by state and local immigration laws argues against a policy that encourages the proliferation of such laws.

The creation of a sensible, coherent, forward-looking immigration system is incompatible with measures that eliminate the ability to make sensible individualized decisions on immigration cases, expand expensive and arbitrary mandatory detention and deportation, create a burdensome patchwork of potentially conflicting and unconstitutional state and local immigration laws, and criminalize the entire unauthorized population. In other words, when the House leadership considers what immigration bills to put forward as part of its “step-by-step” solution, the SAFE Act should not be on the list. Because it represents outdated principles that are ineffective and inherently in conflict with prevailing and accepted principles of immigration reform, the SAFE Act would undermine and contradict any achievements the House might make to fix our severely dysfunctional immigration system.