Despite some highly public claims to the contrary, there has been no waning of immigration enforcement in the United States. In fact, the U.S. deportation machine has grown larger in recent years, indiscriminately consuming criminals and non-criminals alike, be they unauthorized immigrants or long-time legal permanent residents (LPRs). Deportations under the Obama administration alone are now approaching the two-million mark. But the deportation frenzy began long before this milestone. The federal government has, for nearly two decades, been pursuing an enforcement-first approach to immigration control that favors mandatory detention and deportation over the traditional discretion of a judge to consider the unique circumstances of every case. The end result has been a relentless campaign of imprisonment and expulsion aimed at noncitizens—a campaign authorized by Congress and implemented by the executive branch. While this campaign precedes the Obama administration by many years, it has grown immensely during his tenure in the White House. In part, this is the result of laws which have put the expansion of deportations on automatic. But the continued growth of deportations also reflects the policy choices of the Obama administration. Rather than putting the brakes on this non-stop drive to deport more and more people, the administration chose to add fuel to the fire.

IRCA and the New Era of Deportations

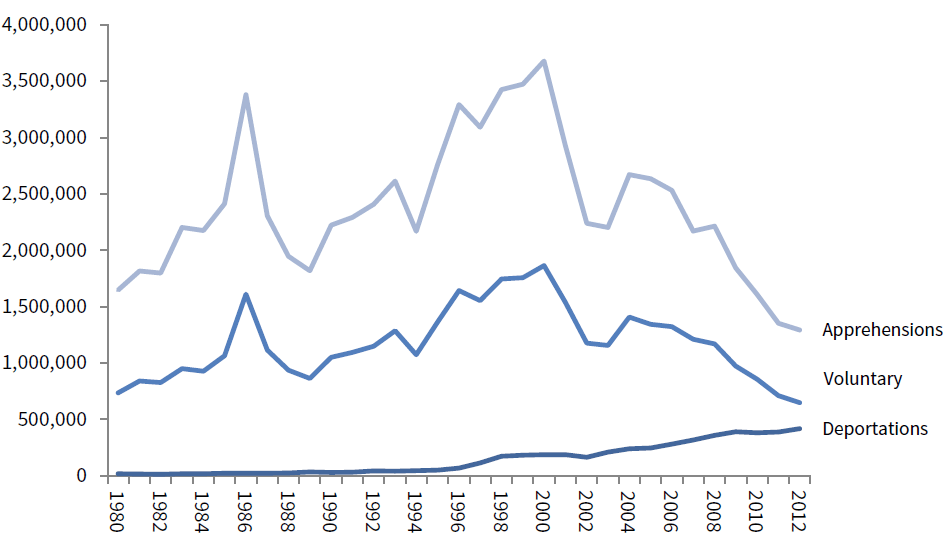

The U.S. system of deportation (and immigration detention) has been growing for decades under both Republican and Democratic administrations and congresses. The impetus for this growth was a small section of the Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986 (IRCA) known as the MacKay amendment, which encouraged the initiation of deportation proceedings against any immigrant convicted of a deportable offense. Since that time, a stream of punitive legislation has eaten away at the traditional discretion of judges to grant relief from deportation in particular cases. The end result is that the number of “removals” (deportations) has trended upward since the mid-1990s. Meanwhile, the number of apprehensions has fluctuated widely, primarily in response to changing economic conditions in the United States and Mexico, and nose-dived when the recession of late 2007 hit. The number of “voluntary returns” has tracked apprehensions closely. However, since 2005, voluntary return has been made available to fewer and fewer apprehended immigrants as deportation (with criminal consequences for re-entry into the country) becomes the preferred option of U.S. immigration authorities (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Apprehensions, Voluntary Returns, and Deportations, 1980-2012

Source: U.S. Department of Homeland Security, 2012 Yearbook of Immigration Statistics, Data Tables 33 & 39.

Most unauthorized immigrants (and deportees) have long been men. However, faced with intensified immigration enforcement, men who in the past might have returned to their home countries after a few years of work in the United States are settling permanently and bringing their wives and children with them. At the same time, immigration enforcement has expanded along the full length of the southern border and into the interior of the country, beyond the border crossing points traditionally dominated by men. As a result, more and more women (and mothers) are being apprehended and deported.

Be they men or women, though, most of the immigrants being deported are not dangerous criminals. According to U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) statistics, four-fifths of all deportations conducted by the agency in Fiscal Year (FY) 2013 did not fit ICE’s own definition of what constitutes a “Level 1” priority.

The 1996 Laws

The most extreme cases of punishing post-IRCA immigration laws came in 1996 with the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act (IIRAIRA) and Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act (AEDPA). These two pieces of legislation transformed immigration law in two ways. First, the laws mandated the detention and deportation of noncitizens (legal permanent residents and unauthorized immigrants alike) who had been convicted of an “aggravated felony.” Second, the laws expanded the list of offenses which qualify as “aggravated felonies” for immigration purposes (including tax evasion, failure to appear in court, and receipt of stolen property). Moreover, the laws also applied this new standard retroactively to offenses committed years before the laws were enacted. In other words, a growing number of immigrants have been detained and deported for non-violent criminal offenses since 1996 as U.S. immigration policy criminalizes an ever-broadening swath of the immigrant population.

An Enforcement Spending Spree

Thanks to the proliferation of punitive laws and policies, immigration enforcement is a booming business. Since the federal government adopted a strategy of concentrated border enforcement known as “prevention through deterrence” in the early 1990s, the annual budget of the Border Patrol has increased ten-fold, from $363 million in FY 1993 to $3.5 billion in FY 2013 (Figure 2).

Figure 2: U.S. Border Batrol Budget, FY 1993-2013

Source: U.S. Border Patrol, “U.S. Border Patrol Fiscal Year Budget Statistics,” January 27, 2014.

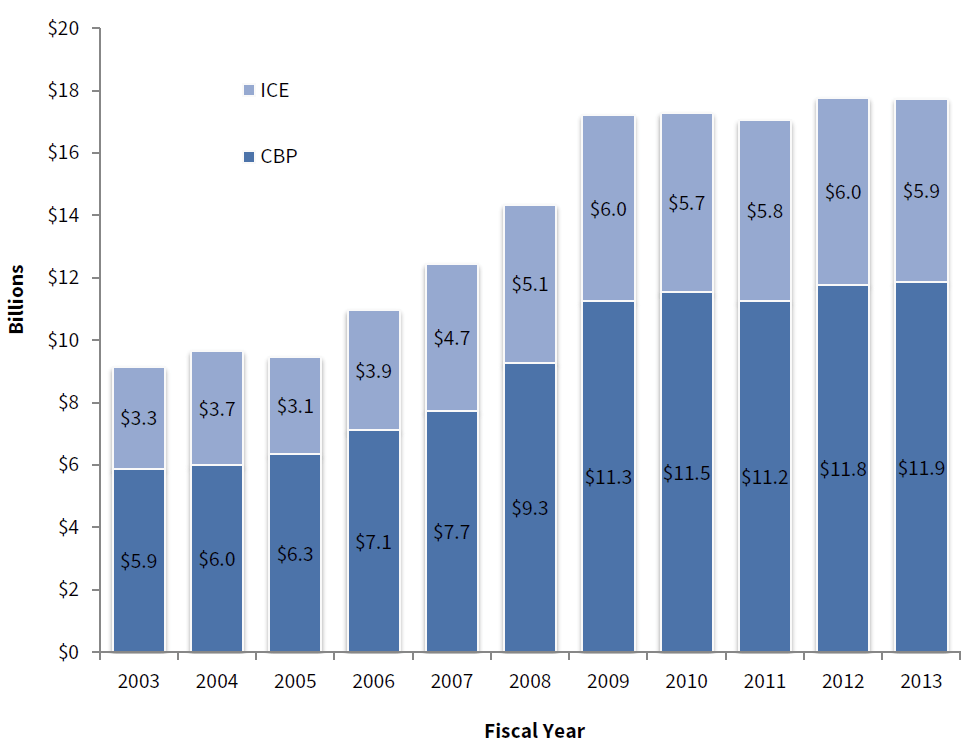

Moreover, since the creation of the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) in 2003, the annual budget of Customs and Border Protections (CBP)—which includes the Border Patrol—doubled from $5.9 billion to $11.9 billion in FY 2013. Spending on Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE)—the interior-enforcement counterpart to CBP within DHS—grew 73 percent, from $3.3 billion since its inception to $5.9 billion in FY 2013 (Figure 3). The budget of Enforcement and Removal Operations (ERO) in particular has increased from $1.2 billion in FY 2005 to $2.9 billion in FY 2012.

Figure 3: CBP & ICE Annual Budgets, FY 2003-2013

Source: U.S. Department of Homeland Security, Budget-in-Brief, FY 2005-2014.

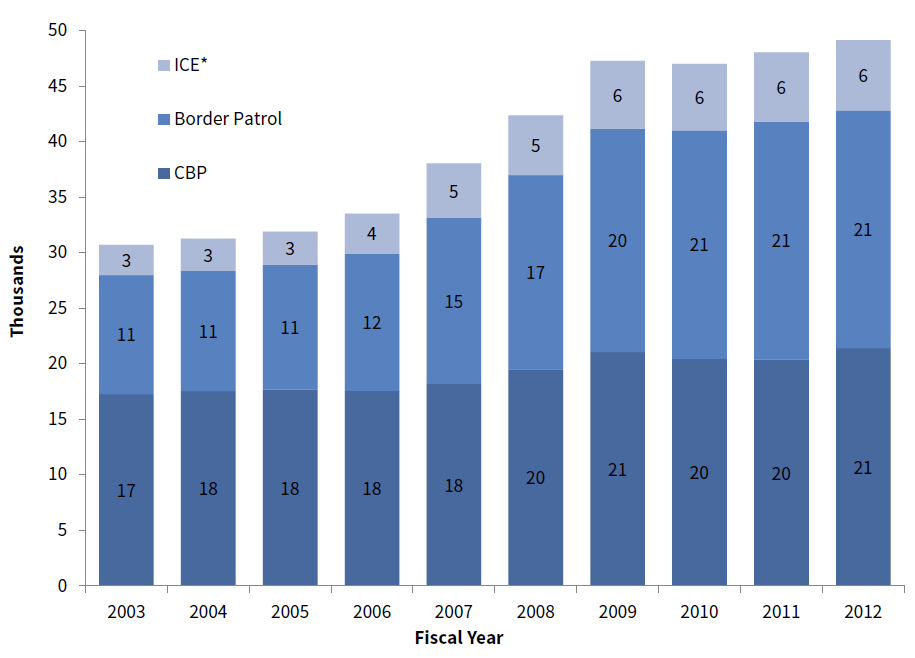

As budgets have grown, so has staffing. The number of Border Patrol agents deployed between ports of entry roughly doubled from 10,717 in FY 2003 to 21,394 in FY 2012. At the same time, the number of CBP officers working at ports of entry grew from 17,279 to 21,423. And the number of ICE agents devoted to Enforcement and Removal Operations more than doubled from 2,710 to 6,338 (Figure 4). All told, the number of border and interior-enforcement personnel now stands at roughly 49,000.

Figure 4: CBP Officers, Border Patrol Agents, and ICE Agents, FY 2003-2012

Source: see endnotes 15, 16, and 17. * Includes only ERO Officers.

The Melding of Border and Interior Enforcement

All of this spending on immigration enforcement has fueled programs like the Criminal Alien Program (CAP), Secure Communities, and 287(g), which reach into every corner of the country and thereby blur the line between interior enforcement and border enforcement.

Criminal Alien Program (CAP)

CAP encompasses a number of different systems designed to identify, detain, and begin removal proceedings against deportable immigrants within federal, state, and local prisons and jails. CAP is currently active in all state and federal prisons, as well as more than 300 local jails throughout the country. It is one of several “jail status check” programs intended to screen individuals in federal, state, or local prisons and jails for removability. While other such jail status check programs (like Secure Communities) have garnered much more attention, CAP is the oldest and largest such interface between the criminal justice system and federal immigration authorities. CAP was created between 2005 and 2007 through the fusion of two other programs that were launched in 1988: the Institutional Removal Program (IRP) and the Alien Criminal Apprehension Program (ACAP).

Secure Communities

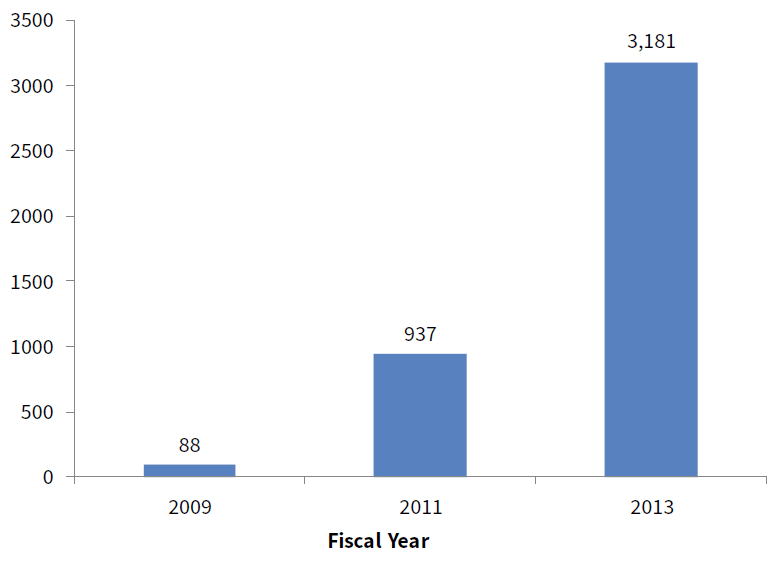

Secure Communities, which was created in 2008, is an information-sharing program between DHS and the Department of Justice. The program uses biometric data to screen for deportable immigrants as people are being booked into jails. Under Secure Communities, an arrestee’s fingerprints are run not only against criminal databases, but immigration databases as well. If there is an immigration “hit,” ICE can issue a “detainer” requesting that the jail hold the person in question until ICE can pick him up. Not surprisingly, given the new classes of “criminals” created by IIRAIRA, most of the immigrants being scooped up by Secure Communities are non-violent, are not serious criminals, and are not a threat to anyone. Moreover, as the program metastasized throughout every part of the country, more and more people were thrown into immigration detention prior to deportation. The expansion of Secure Communities has been dramatic, to say the least—in part because participating jurisdictions cannot opt out of the program. In fact, the number of “activated jurisdictions” encompassed by the program grew from only 88 in FY 2009 to 937 in FY 2011 to all 3,181 in the country as of FY 2013 (Figure 5). According to the Government Accountability Office (GAO), “from October 2008 through March 2012, Secure Communities led to the removal of about 183,000 aliens.”

Figure 5: Secure Communities Activated Jurisdictions

Source: see endnote 23.

287(g)

Under Section 287(g) of the Immigration and Nationality Act, DHS may deputize selected state and local law-enforcement officers to perform the functions of federal immigration agents. Like employees of ICE, these “287(g) officers” have access to federal immigration databases, may interrogate and arrest noncitizens believed to have violated federal immigration laws, and may lodge “detainers” against alleged noncitizens held in state or local custody. The program has attracted a wide range of critics since the first 287(g) agreement was signed more than ten years ago. Among other concerns, opponents say the program lacks proper federal oversight, diverts resources from the investigation of local crimes, and results in profiling of Latino residents—as was documented in the case of the 287(g) agreement with Sheriff Joe Arpaio of Maricopa County, Arizona. In its budget justification for FY 2013, DHS sought $17 million less in funding for the 287(g) program, and said that in light of the expansion of Secure Communities, “it will no longer be necessary to maintain the more costly and less effective 287(g) program.”

The “Consequence Delivery System”

Meanwhile, along the U.S.-Mexico border, CBP began in 2005 to roll out its punitive “Consequence Delivery System” aimed at immigrants caught crossing the border without authorization. As described by Border Patrol Chief Michael J. Fisher, Consequence Delivery “uses a combination of criminal and administrative consequences developed by the Border Patrol, and implemented with the assistance of ICE, targeting specific classifications of offenders, effectively breaking the smuggling cycle along the border of the United States.” In practice, this means that fewer apprehended Mexicans are given the option of “voluntary return” to Mexico. Rather, the Border Patrol now opts for three types of “high consequence” outcomes: formal removal (deportation), immigration-related criminal charges, and remote repatriation (that is, sending immigrants to remote locations far from the smugglers who helped them cross the border). In other words, unauthorized Mexican immigrants are no longer allowed to just go home. They may face criminal prosecution and prison time if they return to the United States. They also are being sentenced in group “trials” that accord apprehended immigrants few legal rights—a process known as Operation Streamline. According to the Congressional Research Service (CRS), 208,939 unauthorized immigrants were prosecuted through Operation Streamline from its initiation in December 2005 through the end of FY 2012.

Roots in the United States

Many of the immigrants now being deported are long-term legal permanent residents of the United States who have run afoul of the 1996 laws. Yet even many of the unauthorized immigrants being deported have strong ties to the United States, such as U.S.-citizen family members (especially U.S.-born children), not to mention jobs and homes in the United States. Families containing a member who is an unauthorized immigrant live in constant fear of separation. And the burden of deportation is shouldered disproportionately by children. According to estimates from the Pew Hispanic Center, there are 4 million U.S.-born children in the United States with at least one parent who is an unauthorized immigrant, plus 1.1 million children who are themselves unauthorized immigrants and have unauthorized-immigrant parents. Moreover, DHS estimates that nearly three-fifths of unauthorized immigrants have lived in the United States for more than a decade. In other words, most of these people are not single young men, recently arrived, who have no connection to U.S. society. These are men, women, and children who are already part of U.S. society.