The Institutional Hearing Program (IHP) (sometimes known as the Institutional Hearing and Removal Program) permits immigration judges to conduct removal proceedings for noncitizens serving criminal sentences in certain correctional facilities. New scholarship, a government watchdog report, and records uncovered through Freedom of Information Act litigation have uncovered more information about this previously little-known program. A readily apparent problem with the IHP is that most noncitizens do not have access to attorneys who can represent them in their deportation hearings. Typically, these individuals fare much worse than those with an attorney.

This fact sheet provides an overview of the IHP’s history and what is known about the way it works. It also highlights some of the due process concerns that surround the program.

History and Overview of the Institutional Hearing Program

The IHP was created to meet a requirement of the Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986 (IRCA), which stated that: “In the case of an alien who is convicted of an offense which makes the alien subject to deportation, the Attorney General shall begin any deportation proceeding as expeditiously as possible after the date of the conviction.” In 1998, the former Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) established two programs to comply with this requirement: the IHP, which initially operated in federal and state prisons holding the largest numbers of deportable noncitizens, and the Alien Criminal Apprehension Program (ACAP), which operated in all other prisons and jails. Between 2005 and 2007, the IHP and ACAP were combined within the Criminal Alien Program (CAP).

There is relatively little public information available about how the IHP functions at the state and local level. For instance, a 2018 Executive Office for Immigration Review (EOIR) fact sheet on the IHP references only “federal inmates who may be removable from the United States.” The fact sheet also describes the program as being jointly administered by EOIR and the Bureau of Prisons (BOP), both within Department of Justice (DOJ), together with Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), which is within the Department of Homeland Security (DHS). More recently, U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) began to play a coordinating role.

The number of removals conducted through the IHP grew dramatically for several years after the program’s creation, starting at 1,409 in Fiscal Year (FY) 1988 and peaking at 18,018 in FY 1997. However, IHP removals plummeted after the enactment of the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act of 1996 (IIRAIRA) and the Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act of 1996 (AEDPA). IIRAIRA and AEDPA, along with the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994, added to the list of offenses for which a noncitizen could be deported and made it easier to carry out deportations without a court hearing. As a result, the number of removals conducted through the IHP dropped rapidly after FY 1997.

The Trump administration sought to breathe new life into the IHP. On February 20, 2017, then acting Secretary of Homeland Security John Kelly issued a department-wide memorandum on “Enforcement of the Immigration Laws to Serve the National Interest.” The memorandum reaffirmed the U.S. government’s commitment to utilize the IHP to initiate removal proceedings against noncitizens “incarcerated in federal, state, and local correctional facilities.”

Roughly one month after the memorandum was issued, DOJ announced that the IHP would expand in federal prisons to a total of 14 BOP facilities and six BOP contract facilities. By 2019, there were at least 21 federal IHP prisons, including 14 operated by BOP and 7 operated by private contractors. That number dropped to 17 by May 2021. The IHP also operated in state and local facilities in 19 states in 2019: Arizona, California, Connecticut, Florida, Georgia, Illinois, Iowa, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, Nebraska, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Texas, and Wisconsin.

An interactive map showing federal and state IHP locations as of 2019 is available here.

How the Program Works

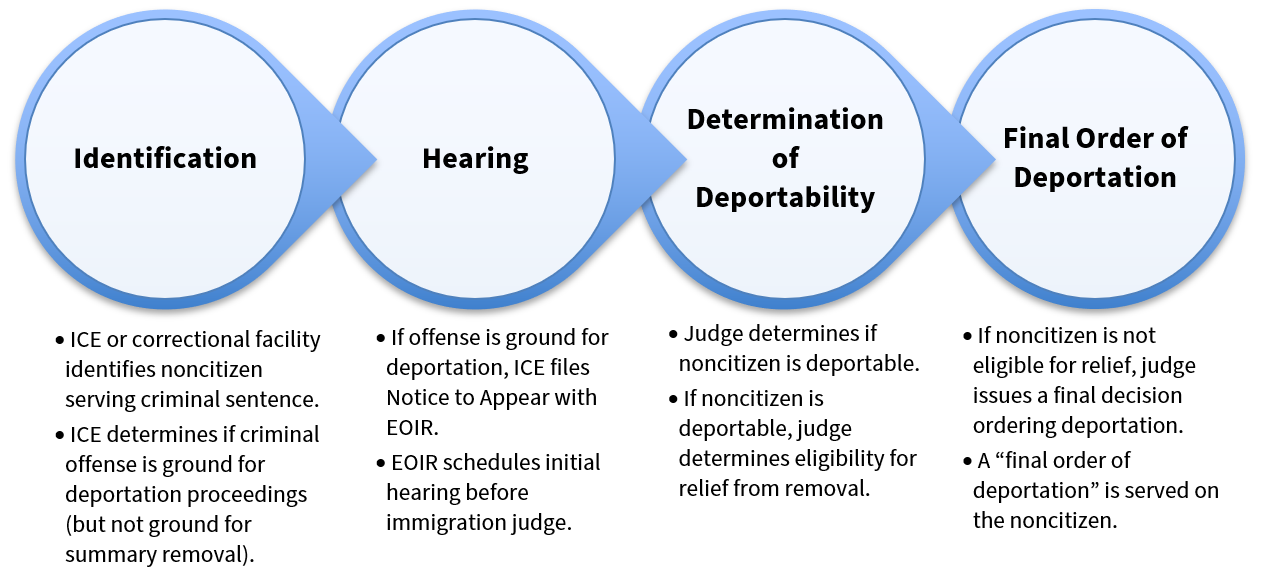

The IHP commences when designated ICE officers identify noncitizens serving criminal sentences. ICE then makes its own determination regarding whether these noncitizens have committed an offense that constitutes a ground for deportation (or whether the noncitizen is otherwise deportable).

If the ICE officer determines that the noncitizen is deportable and can have his or her case heard before an immigration judge, rather than face summary removal under the system enacted in the 1990s, ICE files a “Notice to Appear (NTA)” with EOIR that charges the noncitizen with a deportable offense and initiates removal proceedings. Once ICE files the NTA with EOIR, removal proceedings ensue, according to the statute. EOIR schedules an initial hearing before an immigration judge and the noncitizen is notified. The immigration judge reviews the charges and if the judge determines that the noncitizen is in fact deportable, the judge will determine whether the noncitizen qualifies for any relief from removal.

During a hearing on any application for relief from removal, a noncitizen has the right to submit evidence, review the government’s evidence, and call witnesses. Importantly, a noncitizen has a right to counsel, though the statute specifies that this right is “at no expense to the government.” The judge then issues a final decision. If the judge orders removal, a “final order of deportation” is served on the noncitizen (see Figure 1). As with all removal orders issued through this process, a noncitizen has a right to appeal the decision to the Board of Immigration Appeals (BIA) and, in many cases, can seek judicial review before the federal courts of appeals.

While ICE is an essential actor in the IHP, the federal and state correctional institutions that host the IHP also play an important role. There is almost no public information about how state correctional authorities facilitate the IHP within their prisons and jails. But the BOP has produced records in response to a FOIA request that reveal the close coordination between BOP and ICE to ensure that all non-U.S. citizens in BOP custody are evaluated by ICE for possible placement in IHP proceedings. The records show that BOP affirmatively identifies all non-U.S. citizens in its custody, provides necessary information to ICE, and confirms that ICE screens each individual for the IHP.

Figure 1. The Steps of the Institutional Hearing Program

Due Process Concerns

Individuals who pass through IHP proceedings are more likely to be deported than noncitizens in non-IHP removal proceedings. According to a 2020 study, 93 percent of all IHP participants were ordered deported between 1988 and 2019, compared to the 83 percent removal rate for non-IHP removal proceedings during the same period. The Department of Justice’s Office of Inspector General in 2021 reported that out of 3,116 IHP cases opened and completed between 2013 to 2019, just 1 person was granted relief and 35 people had their cases administratively closed or terminated. The rest were ordered removed.

A key problem with the IHP is that most noncitizens lack access to attorneys who can represent them in their deportation hearings. This is due, in part, to the remote locations of many of the facilities participating in the IHP. A 2015 national study of access to counsel in immigration courts found that only 9 percent of incarcerated noncitizens in IHP removal proceedings between 2007 and 2012 were represented by an attorney, compared to 38 percent of non-IHP removal cases. The 2020 study showed little improvement. Between 1988 and 2019, only 10% of IHP participants were represented by counsel, with an even lower rate (3.5 percent) at federal contract facilities.

Not surprisingly, individuals in removal proceedings who do not have an attorney fare much worse than those with an attorney. The 2015 study found that, in general, only 2 percent of detained noncitizens without attorneys achieved favorable outcomes in their cases, compared to 21 percent of those with attorneys.

The disparity between represented individuals and unrepresented individuals is reflected in the IHP. At the state IHP level, 93 percent of people without an attorney received a removal order between 1988 and 2019, compared to 84 percent of people with an attorney during the same period. At the federal level, DOJ reports that only four percent of the IHP cases completed in FY 2018 had representation. Among cases without representation, 97 percent culminated in an order of removal, compared to 72 percent of cases with representation. As the Supreme Court has noted, discerning the immigration consequences of criminal convictions is “quite complex.” Thus, the importance of counsel is particularly acute for individuals who appear on the IHP immigration court docket.

In addition to the problem of access to counsel, the manner in which many IHP deportation hearings are conducted raises other due process concerns. Increasingly, immigration judges conduct the hearings by video teleconference (VTC) rather than in person. According to DOJ, 54 percent of federal IHP case hearings were conducted by VTC in FY 2018.

The Trump administration sought to increase the use of VTC proceedings as part of its effort to expand and modernize the IHP. However, a study conducted by Booz Allen Hamilton at the behest of EOIR found that “faulty VTC equipment, especially issues associated with poor video and sound quality, can disrupt cases to the point that due process issues may arise.” Moreover, the study noted that “it is difficult for judges to analyze eye contact, nonverbal forms of communication, and body language over VTC.”

In other words, noncitizens subject to VTC hearings are at a distinct disadvantage compared to those who appear before a judge in person. While the immigration statute permits hearings to be conducted by VTC, courts have reiterated that these proceedings must nonetheless comport with due process, particularly with regard to the rights to counsel and to examine evidence.