Carlos Gutierrez, a successful businessman in Chihuahua, Mexico, and the married father of two, refused to comply with a criminal cartel’s monthly demands of $10,000. In retribution for his refusal and as an example to other businessmen, his feet were cut off and he was left for dead. According to his former attorney, that kind of “organized crime is not possible without the complicity of the municipal, state and federal police.”

Gutierrez’s friends rushed him to the hospital. He was later able to make his way to the United States to seek asylum and turned himself in to border agents in El Paso After passing a credible fear screening, he was placed in removal proceedings in immigration court, where his asylum case could be decided. His case was later administratively closed as a matter of prosecutorial discretion.The immigration judge’s order leaves Mr. Gutierrez in a precarious situation—a legal limbo with no permanent right to remain in the country and with no decision on his asylum claim unless removal proceedings are reopened.

Gutierrez’s case is just one of the thousands of asylum requests that Mexicans and Central Americans have presented along the U.S.-Mexico border in recent years. As described more fully below, persons seeking admission to the U.S. at a port of entry or near the border who express a fear of return to their countries must be interviewed to determine whether there is a significant possibility that they can establish persecution or a fear of persecution before an immigration judge. If the applicant meets this “credible fear” standard, the case proceeds to a removal hearing in immigration court. There the applicant may apply for asylum or other protections from removal based on persecution or torture. If the applicant cannot meet the initial threshold, he or she is deported immediately under an order of expedited removal.

Recently, the credible fear process has become the target of political attacks. Detractors argue that it is too easy to obtain favorable credible fear determinations and avoid deportation. They point to rising credible fear claims as evidence that people are abusing the system. According to the Acting Chief of the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) Asylum Division, there were an “unprecedented number of credible fear referrals” during Fiscal Year (FY) 2012. In draft Congressional testimony in mid-2013, USCIS Associate Director Joseph Langlois noted that two-thirds of such claims came from Salvadorans, Hondurans, and Guatemalans, most of which were presented in the Rio Grande Valley in South Texas. He attributed the rise “to reports of increased drug trafficking, violence and overall rising crime in those countries.”

While the numbers are rising, political attacks are made without reference to how the credible fear and asylum processes actually work, to escalated violence in Mexico and Central America, and to the barriers to obtaining asylum in the United States. This paper addresses these issues, summarizes the concerns and experiences of numerous advocates in the field, and concludes that the credible fear and asylum process poses obstacles for applicants that far surpass the supposed abuses claimed by its detractors.

Prior to 1996, persons seeking asylum in the United States could apply directly to the immigration service or, if they were charged with immigration violations, they could apply for asylum in the context of deportation or exclusion proceedings in immigration court. The asylum process was essentially the same regardless of whether someone was intercepted at the border, deemed inadmissible while attempting to enter the United States at an airport or other port of entry, or arrested and placed in proceedings after many years in the U.S.

In 1996, however, Congress enacted a streamlined removal procedure known as “expedited removal” (explained below) that allows immigration officers to issue orders of removal under certain circumstances without affording the person an opportunity to appear before an immigration judge. If applicants establish a credible fear of persecution, they are allowed to apply for asylum in removal proceedings. This process has been criticized as both too harsh and too lenient. Detractors claim that increased claims come from ineligible individuals who apply and subsequently disappear. Yet, as country conditions deteriorate in Mexico, Central America, and other parts of the world, more people arrive at the border intending to apply for asylum. Upon stating their intent to apply for asylum, they are taken into custody, and may languish in detention, often in remote facilities. And if released from detention, immigration courts are so under-resourced that individuals must wait for years for the merits of their cases to be adjudicated.

In August 2013, House Judiciary Committee Chairman Bob Goodlatte (R-VA) called the credible fear process a “loophole.” Contrary to the actual numbers, he claimed Mexicans with fraudulent claims were responsible for the increase. Conservative media joined the fray, pointing to increased numbers of asylum seekers from Mexico and Central America and calling it an “effective tactic” to remain in the U.S., and suggesting that many asylum claims are fraudulent. The release from detention of young DREAMer activists in the summer of 2013 after passing credible fear interviews also “provoked the ire of House Republicans, drawing attention to a broader policy that has led to large increases in the numbers of migrants gaining entry by requesting asylum at the southwest border.”

In response to these concerns, the U. S. House of Representatives Judiciary Committee held hearings in December 2013 and February 2014 provocatively entitled, “Asylum Abuse: Is It Overwhelming Our Borders?” and “Asylum Fraud: Abusing America’s Compassion?” The premises of those hearings were that criminals were “gaming” the system by claiming a credible fear of persecution and that such abuse and fraud in the credible fear process warranted tightening of the process.

Answering the claims of Representative Goodlatte, Eleanor Acer, Director of the Refugee Protection Program at Human Rights First, testified that preventing abuse of the asylum system is critical. But, as she pointed out, U.S. authorities already have a range of effective tools to address abuses. Furthermore, Congress and the Obama administration could take further steps to ensure the integrity of the asylum process, including providing more resources to the asylum office and immigration court system to prevent backlogs. Equally important is lessening the “many barriers and hurdles” that Congress has placed in the path of asylum seekers over the years.”

More recently, USCIS also responded to the increase in credible fear claims and perceptions of abuse. In February 2014, without requesting public comment or providing notice, the USCIS revised its credible fear instruction materials for asylum officers. Applicants now must “demonstrate a substantial and realistic possibility of succeeding” in their cases. Many advocates fear that the new guideline undermines the role of a credible fear finding as a threshold determination. According to Professor Bill Ong Hing, “[A] fair reading of the Lesson Plan leaves one with the clearly improper message that asylum officers must apply a standard that far surpasses what is intended by the statutory framework and U.S. asylum law.”

The reality is that the entire credible fear and asylum process, from refugee attempts to enter and apply for asylum through subsequent interviews and hearings, is replete with hurdles. In the words of Paul Rexton Kan, Associate Professor of National Security Studies at the U.S. Army War College, “enduring the asylum process is not easy.” The obstacles to asylum stem from the government’s failure to follow laws, rules, and policies, as well as inadequate funding for the administrative bodies and courts that hear asylum claims.

The General Rules for Applying for Asylum

In 1980, President Ronald Reagan signed the Refugee Act into law, thereby bringing the United States into compliance with the 1967 United Nations Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees. Under the act, in order to apply for asylum, an individual must be present in the United States and demonstrate a well-founded fear of persecution based on one of five grounds: race, religion, nationality, political opinion, or membership in a particular social group.

An individual can apply for asylum affirmatively or defensively. If immigration officials have never apprehended the individual, he or she may apply before the USCIS asylum office within one year of entering the United States. If the individual is not granted asylum, the case is referred to the immigration court for removal proceedings under the Executive Office of Immigration Review (EOIR). The individual may renew the asylum request in court and also apply for withholding of removal and relief under the Convention Against Torture (CAT). Both withholding of removal and CAT have higher burdens of proof than asylum. And unlike asylum, these remedies do not offer a path to permanent resident status, as is offered to asylees after one year of residence.

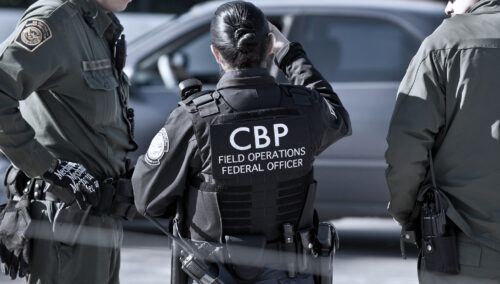

Individuals may also apply for asylum defensively after they have been apprehended by U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) or U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agents and are placed in removal proceedings in immigration court. Individuals may be deportable unless they can show eligibility for a remedy such as asylum, withholding of removal, or relief under CAT. Prior to 1997, individuals with asylum claims arrested at the border or in the interior of the country could present their cases at adversarial hearings before immigration judges.

The Special Expedited Removal Rules for Applying for Asylum

In 1996, as part of the Illegal Immigration and Immigrant Responsibility Act (IIRIRA), Congress enacted a new provision called “expedited removal.” It allows the summary expulsion of noncitizens who have not been admitted or paroled into the U.S., have been in the U.S. for less than two years, and who are inadmissible because they presented fraudulent documents or have no documents. Unless they express a fear of persecution or torture upon return to their home countries or indicate an intention to apply for asylum, such individuals may be removed right away and will be barred from returning to the U.S. for at least five years (but often much longer).

Initially, the former Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) applied expedited removal only to individuals arriving at ports of entry. However, over time, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) announced that it would apply expedited removal along the entire U.S. border, including all coastal areas adjacent to the country’s maritime borders. Currently, the government applies expedited removal to apprehensions made within 100 miles of the border.

In addition to expedited removal, IIRIRA also instituted two provisions that affect and bar asylum. The first is a one-year filing deadline. With limited exceptions, an applicant who does not file for asylum within a year of entering the country is barred from doing so. The second bar is Reinstatement of Removal. If an individual is removed or voluntarily leaves under an order of removal and subsequently reenters illegally, he or she faces the reinstatement of the previous removal order. Upon return, DHS bars the individual from asylum and other remedies except for withholding of removal or CAT protection.

As explained below, the expedited removal process involves three agencies within DHS: 1) CBP, which makes the initial determination of removal and refers an individual to a 2) USCIS asylum officer who conducts an interview to determine whether the individual has a credible or reasonable fear of persecution; and 3) ICE, which detains the individual and makes parole decisions. Individuals who are not deemed “arriving aliens,” are eligible for bonds, and an immigration judge within EOIR, a branch of the Department of Justice, may review bond amounts. In all of these cases, an immigration judge determines eligibility for relief from removal.

The Initial Encounter with Immigration Officers

Immigration officers must interview individuals who are subject to expedited removal. If an individual expresses an intention to apply for asylum or expresses a fear of persecution or torture upon returning to his or her home country, the inspection officer must refer the individual to a USCIS asylum officer for a credible fear interview. Regulations mandate that inspection officers inform individuals of their rights and create a record of their statements. If an individual requires interpretation, it must be provided. In addition, individuals who wish to apply for asylum must be detained, subject to limited exceptions, during the credible fear process.

The Credible Fear Interview

Credible fear of persecution is defined by statute as “a significant possibility, taking into account the credibility of the statements made by the alien in support of the alien’s claim and such other facts as are known to the officer, that the alien could establish eligibility for asylum under section 1158 of this title.” Until recently, this standard was to be a preliminary threshold, designed as a fairly low bar due to its use as a screening mechanism. But USCIS has recently issued instructions to asylum officers to use a more rigorous standard that is more akin to the standard applied at merit hearings. The new instructions may prevent many asylum seekers from passing the credible fear stage and having their asylum claims fully considered in immigration court.

If the individual cannot demonstrate a credible fear of persecution or torture, she or he can ask an immigration judge to review the negative decision. If the judge concurs with the prior negative decision, the individual has no right to appeal and must be removed from the United States. If, due to a previous deportation or other bar, the individual cannot apply for asylum, but nevertheless expresses fear of persecution or torture, he or she can apply for withholding of removal or protections under the CAT. Asylum officers must interview such individuals to determine whether they have “reasonable fear” of persecution or torture. If they pass that interview, they can bring their claims to immigration court and have them heard before a judge. If they do not pass the interview, they are summarily removed.

The Process After the Credible Fear Interview

If the USCIS asylum officer issues a favorable determination of credible or reasonable fear, the officer issues a Notice to Appear (NTA) requiring the individual to appear in immigration court for removal proceedings. While USCIS asylum officers must ensure that applicants understand the credible fear process, they are not required to advise applicants on what follows their credible fear interviews, leaving individuals in the dark as to how to pursue their claims. After ICE files the NTA with the court, a removal hearing is held before an immigration judge. Asylum and other claims such as withholding of removal or relief under CAT can be heard in that proceeding.

Release from Detention

Although detention of asylum seekers in expedited removal proceedings is mandatory, it becomes discretionary as soon as individuals pass credible fear. Due to inconsistent application of ICE’s own policies and high bonds, however, asylum seekers may languish in detention for months, if not years, thus exacerbating post-traumatic stress and other harms asylum seekers may have suffered in their own countries.

In 2009, in an effort “to ensure transparent, consistent, and considered” determinations for arriving aliens seeking asylum, ICE issued parole guidelines. Effective January 2010, individuals with favorable credible fear determinations who can prove their identity and are not flight risks and do not pose a danger to the community, may be paroled from detention. The guidelines only affect “arriving aliens,” i.e., individuals who present themselves at a port of entry. Regulations allow such individuals to be paroled for urgent humanitarian or significant public interest reasons. Immigration judges do not have jurisdiction to review ICE’s parole decisions. Individuals subject to the expedited removal process who are not deemed “arriving aliens” (i.e., those who have been apprehended after entering the United States, but within 100 miles of the border), may ask an immigration judge to set a bond for their release.

At the December 2013 House Judiciary Committee hearing, Ruth Ellen Wasem, Specialist in Immigration Policy at the Congressional Research Service, reported a “surge” in credible fear requests in FY 2013, noting that “a handful of countries lead the increase: El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, and to a lesser extent Mexico, India, and Ecuador….” But as Ms. Wasem pointed out, “an increase in asylum or credible fear claims in and of itself does not signify an increase in the abuse of the asylum process any more than a reduction in asylum or credible fear claims signifies a reduction in the abuse of the asylum process.” From October 2010 to the present, USCIS data show that El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, and—in smaller numbers—Mexico have tended to be among the top five countries of origin of individuals presenting credible fear claims.

Though the numbers of credible fear claims have increased and may create a strain on the adjudication system, the raw numbers are not enormous. Credible fear claims represent “a tiny portion of the millions of travelers who legally enter the country each year.” Moreover, the numbers of asylum claims in general have not reached the levels of the mid-1990s. Nevertheless, the numbers are rising, and these increases are not surprising. Even the U.S. government concedes that these countries have abysmal human rights conditions. U.S. State Department Reports on Country Conditions show that while the particularities may vary, each of these countries suffers from widespread institutional corruption; police and military complicity in serious crimes; societal violence, including brutality against women and exploitation of children; and dysfunctional judicial systems that lead to high levels of impunity.

Central Americans began seeking asylum in the U.S. in 1980 due to civil wars that ravaged the region. Their cases faced a decades-long history of wrongful practices and unfair asylum denials by the U.S. government. Salvadorans and Guatemalans have had to file several major lawsuits in order to obtain fair and equal treatment by immigration officials. Recent claims from those countries arise from escalating gang violence, narco-trafficking, and the failure of judicial systems to institute justice.

Mexico’s increase in claims is largely due to violence by a combination of cartel, military, and government actors, accompanied by widespread judicial impunity. Since 2006, when former President Felipe Calderon initiated a war on drugs, at least 130,000 Mexicans have been murdered and 27,000 have officially disappeared. Former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton described Mexico as an “insurgency” that is “looking more and more like Colombia looked 20 years ago.” The murder of six members of the Reyes Salazar family, community activists in the Juarez Valley of the state of Chihuahua— “the deadliest place in Mexico” —and the flight of the remaining extended family to the U.S., illustrates the nature of violence in Mexico in recent years.

In 2005, the U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom (USCIRF) conducted a legally mandated study of expedited removal to determine whether the new procedure impaired U.S. obligations to asylum seekers. The report concluded that some CBP agents dissuaded people from requesting asylum, did not record their fears of persecution, and did not refer them for credible fear interviews; immigration judges based decisions on “unreliable and incomplete” reports in the initial stages of the process; and asylum seekers were detained in jails and not released according to established criteria after they passed credible fear interviews. The report concluded that the procedure was replete with deficiencies and set forth numerous recommendations. Additional studies have also noted these problems.

Many of those same flaws still plague the expedited removal system. During telephonic interviews conducted in February 2014 and in correspondence, advocates reported that asylum seekers face significant hurdles beginning with their initial encounters with CBP officers and continuing to their merit hearings in immigration court. We heard frequent complaints that CBP officers often dissuade people from seeking asylum, sometimes berating and yelling at them. Some advocates complained that clients were harassed, threatened with separation from their families or long detentions, or told that their fears did not amount to asylum claims.

El Paso private immigration attorney: “We’ve encountered people who say they expressed a fear of persecution and were told by CBP that the U.S. doesn’t give Mexicans asylum, and they are turned back.”

Florida non-profit organization attorney in facility where detainees are transferred from the border: “CBP doesn’t do its job and ask the right questions about fear of return. People are removed under expedited removal and then come right back because they are afraid. Then they are only eligible for a reasonable fear interview and withholding of removal and are detained for a long time.”

Other attorneys noted that CBP conducted initial interviews too rapidly, without confidentiality, and without properly interpreting interviews or translating documents back to applicants. The resulting discrepancies, such as erroneous birth dates, were later used against applicants in court. Many attorneys stated that they routinely saw identical boilerplate statements in officers’ reports and that officers often failed to record asylum seekers’ statements even though clients told attorneys they had provided specific information to the officers.

El Paso attorney at non-profit: “Judges look at discrepancies between the immediate interview at the port of entry and a credible fear interview. CBP and asylum officers speak Spanish but our clients speak indigenous languages and little Spanish. They rarely get adequate interpretation.”

Similarly, even if an applicant is passed on for a credible fear interview, lack of resources and confusing policies reduce the chances that an applicant may pass the threshold test. In our interviews, attorneys and advocates also complained that detained asylum seekers may wait from one to two months for credible fear interviews. An attorney in Harlingen reported that until recently waits were as long as five months. Attorneys in some locations such as El Paso and south Florida report waiting periods from three months to a year for reasonable fear interviews. Several advocacy organizations and a private law firm recently filed a class action lawsuit challenging the long delays in reasonable fear interviews for detained persons.

Advocates also reported that credible fear decisions lack consistency and sometimes result in conflicting decisions on the same facts. In one case in El Paso, for example, a family reported the wife’s brutal sexual assault to the police and subsequently received threats. The woman did not pass credible fear, but her husband did, even though his claim was based on the assault against her. A December 2013 New York Times story reported similar disparities in treatment of asylum claims based on identical facts. Amparo Zavala fled from Michoacan, Mexico with her extended family to escape cartel violence after a bullet was shot into their house. Two weeks later, Ms. Zavala and her daughter-in-law were deported while the rest of her family was allowed to remain and pursue their asylum claim.

Even when a positive credible fear determination is made, there are reports of failure to actually file charging documents with courts. Applicants whose cases are delayed are at risk that they will be unable to file their asylum claim before the one-year filing deadline ends.

Attorney with non-profit organization: “There are jurisdictional issues. The asylum office won’t take jurisdiction because there was a credible fear interview at the border, but ICE hasn’t filed a notice to appear with the court. People are not told of the one-year deadline. That combined with the notice to appear not filed with the court, results in them missing the one-year deadline. They don’t know where to file their applications and can’t request a change of venue until proceedings are initiated.”

In some areas, advocates report that parole is currently denied to detained persons without regard to the factors listed in the 2009 parole memo. Parole practices change without explanation and are inconsistent between and even within detention facilities, sometimes for individuals who present the same facts.

Attorney in AZ: “Generally, people aren’t getting paroled. A year ago, people provided information and identity docs to deportation officer and if there was a denial, reasons would be provided. Now people are routinely denied, even when people have stacks of corroborating documents.”

Attorney in El Paso: “Parole is discretionary, and they are denying anyone and everyone parole. We have heard that some deportation officers have recommended parole for certain individuals and then get overruled. My last client paroled was in November 2013.”

Advocates in El Paso report that officers sometimes split families and their cases; some family members—usually mothers and children—are released under Orders of Supervision and may not undergo credible fear interviews while other family members—usually fathers —remain detained and are often denied asylum and deported. Attorneys in Texas and Arizona report that people who are eligible for bonds because they are not “arriving aliens” are ordered bonds ranging from $5,000 to $10,000 that are impossible for them to pay.

These problems are compounded by lack of access to counsel, and a myriad of other issues relating to limited resources in immigration courts. For example, advocates report long waiting periods for hearings. Merits hearings for non-detained asylum seekers are often scheduled years away, exacerbating family separations and/or precarious situations for families remaining in the home countries. Attorneys in El Paso report master calendar hearings scheduled 1-2 years away and merits hearings 1-2 years after that. An attorney with a non-profit organization in Chicago that has clients whose asylum cases started at the border reported that an immigration judge in Chicago has a 4½ year backlog.

Further, free or low-cost services are stretched thin because of the numbers needing representation. Asylum seekers are often held in or transferred to detention facilities where representation is unavailable or limited. An attorney at a non-profit in South Florida reported an influx of detained female Central American asylum seekers transferred from the border, only a small number of whom can receive direct representation. Attorneys in El Paso and Berkeley have reported that they must file Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests to obtain records of credible fear interviews for their clients.

Perhaps the most difficult issue of all, however, is the general hostility to many of the Mexican and Central American asylum claims currently being filed. Despite reports of horrific violence, most Mexican and Central American claims continue to be rejected. Some Mexican journalists and human rights activists have been granted asylum, as have family members of law enforcement and union activists and Central American family members of murdered or tortured persons. But many claims asserted by Central Americans are based on forced gang recruitment, and many claims presented by Mexicans are based on violence, including torture and murder, resulting from resistance to extortion or kidnapping by cartels, military, government officials, and sometimes by a combination of all three. Those claims do not fit neatly within the ever-narrowing definitions established by the Board of Immigration Appeals (BIA) through its decisions, of political opinion or membership in a particular social group.

While the numbers of asylum claimants from Central America and Mexico have increased, USCIS shows low numbers of affirmative asylum grants to Salvadorans, Guatemalans, Hondurans, and Mexicans from FY 2003 to FY 2012. Likewise, immigration courts granted similarly low numbers of defensive asylum claims during those same years. In FY 2012, immigration courts granted asylum at rates of 6% to Salvadoran applicants, 7% to Guatemalan, 7% to Honduran, and 1% to Mexican applications. These figures contrast with asylum grant rates of more than 80% to applicants from Egypt, Iran, and Somalia for the same period.

The federal courts of appeal are not in agreement regarding the required showing for recent Central American and Mexican asylum cases, and despite horrific facts of persecution emanating from this region, they have reversed few BIA decisions denying relief. But some courts have rejected the BIA’s narrow interpretation for eligibility for asylum, with one recent decision disputing the BIA’s analysis of a particular social group for a Mexican police officer who had suffered persecution. The court even expressed wonder at why the U.S. government “wants” to deport him. And some immigration judges have recognized refusal to submit to extortion by gangs as an expression of political opinion, particularly in the context of police involvement and the broader political context.

Given the undisputed levels of violence in Mexico and Central America, it is understandable that its victims flee and seek asylum in the U.S. And while their cases may present complicated legal questions, those issues can only be answered through a fair process allowing asylum cases to be heard in court. Getting there requires the credible fear phase to operate fully and fairly and for its deficiencies to be recognized and remedied.

Asylum seekers in the expedited removal process must navigate a lengthy and complex labyrinth to have their asylum claims considered. And, as new waves of Mexican and Central American applicants raise claims, some lawmakers are attempting to politicize and attack the asylum process, irrespective of the relatively minor role credible fear plays in overall admissions or entries into the U.S.

When Congress instituted expedited removal, it created a procedure that was intended to operate rapidly without compromising U.S. obligations to protect refugees. That balancing of obligations, necessitated by Congress’s decision to create a streamlined process, is often at the heart of allegations of abuse of the system. Human rights organizations have explained that the government already has tools at hand to combat fraud, and that these should be enhanced to make sure that fraud can be effectively identified and combated when it occurs. The courts and asylum offices desperately need additional resources to adjudicate claims in a timely manner. But the government also needs to ensure that officers in the agencies charged with implementing expedited removal and asylum strictly adhere to the regulations, policies, and laws that have been instituted. Otherwise, the government will fail in its obligations of offering protection to refugees.