After September 11th, efforts to reach an immigration accord with Mexico came to a halt. As a result, the Bush administration continues a poorly conceived border-enforcement strategy from the 1990s that ignores U.S. economic reality, contributes to hundreds of deaths each year among border crossers, does little to reduce undocumented migration or enhance national security, increases profits for immigrant smugglers, and fails to support the democratic transition that the administration of Vicente Fox represents for Mexico.

As illustrated by events surrounding the visit of Mexican Foreign Minister Luis Ernesto Derbez to Washington in May, the U.S.-Mexico relationship has deteriorated considerably since the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. Before then, considerable momentum had gathered behind the proposals of a wide range of business associations, labor unions, ethnic and religious groups, and politicians – including President Bush – to reach an agreement with Mexico on regulating and “regularizing” the flow of Mexican workers into the United States. The proposals were based on the common sense recognition that immigrants have become indispensable to the U.S. economy, especially in the service sector. In the absence of legal channels to enter the United States, large numbers of these workers resort to more dangerous illegal routes. The essence of the proposals put forward was to create opportunities for these workers to enter legally and provide legal status to those already living and working in the country. Despite their merits, these proposals were derailed by September 11th as the U.S. government turned its attention to security concerns and Mexico dropped off the political radar screen.

As a result, hopes faded for an immigration accord, leaving President Vicente Fox of Mexico unable to meet the heightened expectations of his countrymen and the Bush administration with failed and costly border-enforcement policies from the 1990s that have increased deaths at the border without reducing undocumented migration or increasing national security, while playing into the hands of immigrant smugglers. The U.S. government must re-focus its attention on reaching an immigration agreement with Mexico in order to bring U.S. immigration policy in line with U.S. economic reality, institute a process by which undocumented immigrants can be screened to identify any individuals who might pose a risk to national security or public safety, decrease the number of needless deaths among border crossers, reduce the power of immigrant smugglers, and support the democratic transition that the Fox administration represents for Mexico. In contrast to the arguments of anti-immigrant advocates, such an accord would enhance national security far more than the current border-enforcement strategy by bringing undocumented immigrants out of the shadows and allowing the U.S. government to keep better track of who is actually in the country.

“The Forgotten Relationship”

During his brief trip to Washington in early May, Foreign Minister Derbez put an optimistic spin on the pronounced cooling of U.S.-Mexico relations over the past year and a half. Speaking at the Center for Strategic and International Studies before meeting with Secretary of State Colin Powell on May 7, Derbez observed that, after September 11th, “it became clear for everybody that for each and every nation, and in particular for Mexico and the United States, priority number one in our relationship is the fight against terrorism.” He went on to express confidence that immigration “has to be a priority, and it is a priority for both Mexico and the United States” and that his visit to Washington would “strengthen the policy we initiated in the last two months…which is a better quality of life in the day-to-day existence of our migrants.”

However, the day after Derbez spoke, on May 8, the House International Relations Committee narrowly approved a nonbinding “sense of Congress” amendment to the Foreign Relations Authorization Act (H.R. 1950), introduced by Representative Cass Ballenger (R-10th/NC), Chairman of the Western Hemisphere Subcommittee, stating that any immigration agreement with Mexico should be tied to the opening of Mexico’s government-owned oil company, Pemex, “to investment by U.S. oil companies.” The amendment states that Pemex is “in need of substantial reform and private investment” in order to “fuel future economic growth, which can help curb illegal migration to the United States.” While the amendment drew little attention in the United States, it caused an uproar in Mexico, where it was seen as evidence of U.S. high-handedness in dealing with its southern neighbor.

The current state of affairs contrasts sharply with the high hopes for a broad bilateral agreement on immigration that characterized the early days of the Bush and Fox administrations, when President Bush stated “that the United States has no more important relationship in the world than the one we have with Mexico” and emphasized the need to “understand that the Mexican worker has had a positive impact on the U.S. economy and that there ought to be some normalization process.” The dramatic change in focus is described in the May/June issue of Foreign Affairs by Derbez’s predecessor, Jorge G. Castaneda, who served in the Fox administration before resigning as foreign minister in January. Castaneda writes that, before September 11th, “both sides had identified the core policies needed to tackle undocumented migration flows from Mexico to the United States: an expanded temporary-worker program; increased transition of undocumented Mexicans already in the United States to legal status; a higher U.S. visa quota for Mexicans; enhanced border security and stronger action against migrant traffickers; and more investment in those regions of Mexico that supplied the most migrants.”

However, according to Castaneda, since September 11th “the United States has replaced its previous, more visionary approach to relations in the western hemisphere with a total focus on security matters.” He writes that in “the post-September 11 world, Latin America finds itself consigned to the periphery: it is not a global power center, but nor are its difficulties so immense as to warrant immediate U.S. concern. In many ways, the region, at least in terms of U.S. attention, has become once again an Atlantis, a lost continent.”

In Castaneda’s view, the U.S. government is making a mistake in allowing Mexico to become part of a “forgotten relationship,” particularly during the country’s first democratic presidency after 71 years of authoritarian one-party rule. Castaneda states that “[d]ealing with Mexico is in many ways the most important regional task facing the Bush administration” because “President Vicente Fox’s consolidation of Mexico’s first democratic transfer of power must be – and be seen to be – a success. There is nothing more important to the United States than a stable Mexico… And the United States has a huge role in making Mexico’s transition to democracy a success, or in contributing to its failure.”

The United States plays such an important role, says Castaneda, because – in evaluating the success or failure of the Fox administration – Mexicans will “judge the state of their country’s relations with the United States,” especially “whether Presidents Fox and Bush deliver on the ambitious bilateral agenda they sketched out” on immigration and border issues before September 11th. According to Castaneda, “both Bush and Fox stated dramatic goals and raised expectations enormously. The United States understandably was forced to put the issue on hold for a time. But what was initially portrayed as a brief interlude will now probably stretch through Bush’s entire first term.”

Failed Border Enforcement Strategy

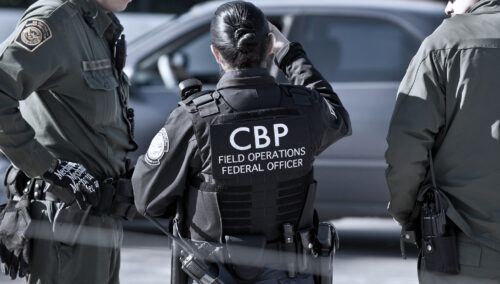

There is another reason the Bush administration should make an immigration agreement with Mexico a high priority: the failure of current border-enforcement strategy. Despite devoting enormous resources since the mid-1990s to fortifying the southwest border with Mexico, the U.S. government has not succeeded in reducing undocumented migration or effectively strengthening border security. Rather, the main results have been expansion of the immigrant-smuggling business and an increase in the number of migrants who die while attempting to cross the border, particularly during summer months when temperatures soar in border areas.

Since September 11th, immigration restrictionists have sought to portray undocumented migration as a threat to national security and an impenetrable border as the solution. However, attempting to “seal the border” is not only impractical given the economic ties between Mexico and the United States, but is too unfocused an approach to effectively enhance security. The Migration Policy Institute noted on September 28, 2001, that using “immigration and border controls to stop terrorists is…a needle-in-the-haystack approach to homeland security.” James M. Lindsay, Senior Fellow in Foreign Policy Studies at the Brookings Institution, and Gregory Michaelidis, Senior Policy Analyst at The Hatcher Group, issued a caution in a November 8, 2001, opinion piece to “not blame illegal immigrants for Sept 11… The vast majority of people who enter the United States illegally are simply looking to improve their lives, not to kill Americans…we can make it harder for terrorists to enter and operate here…without scapegoating immigrants or abandoning the freedoms worthy of a democratic nation.”

According to testimony before the Senate Immigration Subcommittee on February 10, 2000, by Michael A. Pearson, former Executive Associate Commissioner for Field Operations at the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS), U.S. border enforcement policy in the southwest is based on the principle of “‘prevention through deterrence’, that is, elevating the risk of apprehension to a level so high that prospective illegal entrants consider it futile to attempt to enter the U.S. illegally.” Under this strategy, Border Patrol resources are concentrated in traditional border-crossing areas, thereby driving would-be migrants into more rural terrain where they are more readily apprehended.

This strategy was first implemented in El Paso, Texas, in 1993 as Operation Hold the Line. It was extended to California as Operation Gatekeeper, first in San Diego in 1994, then in El Centro in 1998. Next came Operation Safeguard in Arizona, starting with Nogales in 1995 and extending to Douglas and Tucson in 1999. Operation Rio Grande was instituted in McAllen and Laredo, Texas, in 1997. The costs of these operations have been significant. From Fiscal Year (FY) 1994 to FY 2001, the annual INS border-enforcement budget almost tripled to more than $2.5 billion. This amount rose to more than $3 billion in FY 2002.

Although there are no reliable estimates of fatalities among border crossers prior to implementation of the “deterrence” strategy, available statistics indicate a general increase in deaths from exposure, dehydration and drowning as the strategy expanded along the border during the late 1990s. Border deaths have declined somewhat since peaking in 2000, due in part to intensified rescue operations by the U.S. Border Patrol. According to Border Patrol statistics, which include only deaths on the U.S. side of the border, there were 261 fatalities in FY 1998 (the first year aggregate statistics were collected), 250 in FY 1999, 383 in FY 2000, 336 in FY 2001, 320 in FY 2002, and 63 so far this year as of April 14 – a total of 1,613. The Mexican Ministry of Foreign Relations, which counts deaths on both sides of the border, recorded 129 fatalities in calendar year 1997, 170 in 1998, 356 in 1999, 491 in 2000, 391 in 2001, 371 in 2002 and 72 so far this year as of May 12 – a total of 1,980.

Despite the high human and financial costs of the deterrence strategy, there has been no corresponding decline in undocumented migration. An August 2001 report by the General Accounting Office found that the “primary discernable effect of the strategy, based on INS’ apprehension statistics, appears to be a shifting of the illegal alien traffic” from area to area. A July 2002 study by the Public Policy Institute of California concluded that there is no “statistically significant relationship between the build-up and the probability of migration. Economic opportunities in the United States and Mexico have a stronger effect on migration than does the number of agents at the border.” The study found that “the number of unauthorized immigrants in the United States has increased” since the strategy was first implemented, due in part to the fact that “migrants who successfully cross the border stay longer in the United States than they did in the past.” The study also notes that the more dangerous border crossings have led to the “increased use of hired guides, or coyotes,” which “may have expanded the very profitable human smuggling industry.” The deadly consequences of this expansion were driven home on May 14, when 18 (later 19) immigrants who crossed the border into Texas died of asphyxiation while being transported in an unventilated cargo trailer from Harlingen to Houston.

Conclusion

While it is certainly understandable that the events of September 11th delayed consideration of an immigration accord with Mexico, the time has come for the Bush administration to re-direct some of its attention southward. As President Bush remarked on October 26, 2002, he and President Fox share “a mutual desire to deal with the migration issue in a way that recognizes reality, and in a way that treats the Mexican citizens who are in the United States with respect.” By neglecting the U.S. relationship with Mexico, the administration is perpetuating border-enforcement polices that cost billions of dollars and result in hundreds of deaths at the border each year without stemming undocumented migration or improving security. Moreover, the administration is inadvertently weakening the hand of President Fox in the first democratic transition in modern Mexican history.

Rather than funneling immigrants into deadly border terrain and trapping others in the United States, sensible and comprehensive immigration reform would make legality the norm. A well-regulated flow of workers across the border and a process for granting legal status to those law-abiding undocumented immigrants already living in the United States would benefit the U.S. economy, enhance national security by bringing undocumented immigrants out of the shadows, save billions of dollars now wasted treating job seekers as criminals, and weaken the grip of immigrant smugglers.