Every year, Congress is required to consider 12 separate bills to fund the federal government. These bills, which fund agencies such as the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS)—and, within DHS, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) and U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP)—as well as the Executive Office for Immigration Review (EOIR) within the U.S. Department of Justice, have an enormous impact on immigration and immigration enforcement. However, despite the significance of these bills for immigration policy, the “appropriations process” is opaque and unclear to the general public. This fact sheet aims to explain the basics of the federal appropriations process and to show how it affects the world of immigration.

How Does the Appropriations Process Work?

Under Article 1, Section 9, of the U.S. Constitution, “No Money shall be drawn from the Treasury, but in Consequence of Appropriations made by Law.” As a result, Congress has the sole authority to direct how the federal government spends money. Under the Constitution, all government funding bills, also known as appropriations bills, must originate in the House of Representatives before they can be signed into law. However, although the final government funding bill will originate in the House of Representatives, the Senate also has its own government funding process and produces its own bills.

To carry out this process, each year the House and Senate prepare appropriations bills for the upcoming fiscal year. Fiscal years run from October 1 to September 30. For example, Fiscal Year (FY) 2022 runs from October 1, 2021, through September 30, 2022.

Once the House and Senate have both passed a bill funding a particular department, if there are disagreements, the two chambers will engage in a “conference” and hash out the differences before reaching a final agreement. Both houses of Congress will then vote on the bill. If Congress cannot reach an agreement on funding the federal government, Congress passes a “continuing resolution” to extend the previous year’s budget until a new one can be passed. Continuing resolutions have become increasingly common in recent years.

If Congress does not pass the necessary appropriations bills or a continuing resolution, a government shutdown takes place. Under a continuing resolution, the funding levels set in the previous year remain the same, although some changes can be made which are known as “anomalies.”

By law, the president is required to submit a formal budget request for the federal government to Congress between the first Monday in January and the first Monday in February. The annual budget process, however, starts years before a final government funding bill is ever passed. First, agencies spend over a year preparing budget projections and assembling the president’s formal budget request to Congress. That means that government agencies began preparing a budget for FY 2022 during FY 2020. Agencies determine what their spending needs are for each budget line item, such as staffing, capital investment, and new planned operations. This process is carried out in coordination with the Office of Management and Budget (OMB), a White House office that coordinates federal budget policy. Each agency’s budget request, along with accompanying information, is compiled into “Congressional Budget Justifications,” which the President then submits to Congress as a full budget proposal. Because Congress holds the power of the purse, presidential budgets are non-binding and reflect the executive branch’s requests to Congress.

Each Congressional Budget Justification contains detailed information about the operations of the agency and the costs involved in running it. For example, the FY 2022 ICE Congressional Budget Justification contains information such as the average daily cost of detaining an immigrant ($125.06) and per diem rates for detention at various detention centers around the country. Congressional Budget Justifications can be an invaluable tool for individuals seeking an in-depth understanding of the operation of government agencies.

After the president’s budget is published, usually in February, Congress formally begins the process of passing government funding bills. Each chamber has an Appropriations Committee which is tasked with fully funding the federal government, and each Appropriations Committee contains subcommittees that work on funding different federal departments. For example, the House Appropriations Subcommittee on Homeland Security produces a funding bill that covers the entire Department of Homeland Security, including ICE and CBP. Each house of Congress has 12 appropriations subcommittees, which—combined—cover the entire federal government:

The majority of immigration-related appropriations occur in the Homeland Security Subcommittee, which covers DHS and the immigration agencies within it: CBP, ICE, and U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS). EOIR, which houses the immigration courts, falls within the Commerce, Justice, Science, and Related Agencies Subcommittee. Funding for visa processing at U.S. embassies and consulates abroad falls within the State, Foreign Operations, and Related Programs Subcommittee. Funding for the Office of Refugee Resettlement, which covers the unaccompanied children program and helps resettle refugees from around the world, is part of the Labor, Health and Human Services, Education, and Related Agencies Subcommittee.

By law, the annual government funding process formally begins with each chamber passing a resolution allocating a set amount of money that can be used on discretionary spending (i.e. funding which is not required by law, such as payments on government debt, known as a “302(a)” allocation). This is the total amount of money that can be spent in the funding bill. For example, in June 2021 the House passed a “deeming” resolution that allocated $1.506 trillion dollars for discretionary spending for the FY 2022 budget. Each chamber’s Appropriations Committee will then divide this pot of money among the 12 respective subcommittees, allocating a set amount of funding to each one to use for the agencies within each subcommittee’s jurisdiction (known as a “302(b)” allocation).

In order to produce a bill, each subcommittee will hold hearings with the heads of each agency within its jurisdiction in order to question them on the president’s formal budget requests. Individual members of Congress can also influence the process by requesting the inclusion or exclusion of specific items in the ultimate government funding bill. Members of the public can contribute requests as well, either through individual members of Congress or through requests to the relevant committees or subcommittees.

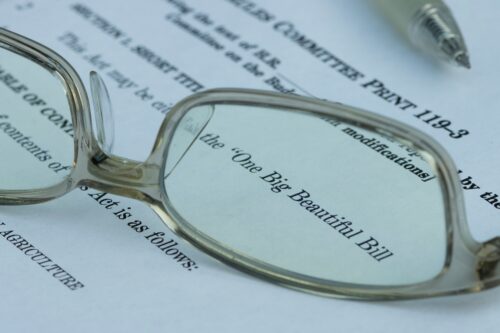

Along with a formal bill to be passed into law, each subcommittee also produces a “committee report,” which is an explanatory statement accompanying the bill. The committee report contains greater detail about the intent of Congress in the bill. These committee reports are quasi-legal, in that they are not voted on by Congress, but—in the words of the Congressional Research Service—“agencies will usually comply with a report’s directives.”

For example, the Homeland Security spending bill generally provides only top-line budget amounts for CBP, ICE, and USCIS, while the committee report breaks down funding for specific components of each agency. As a result, the only way to determine how much money Congress is appropriating for ICE’s “Custody Operations” division is to consult the committee report.

After each subcommittee has produced a bill, it will then be voted on in the full committee. If it passes, then the bill goes to the floor for passage. Appropriations bills may either be passed individually or combined together into an “omnibus” spending bill. This process generally occurs in the House between May and June, and in the Senate between June and July.

When an appropriations bill goes onto the House floor for debate and passage, all members may offer amendments to the bill, or offer objections and points of order regarding specific amendments. There are special parameters often set out during this process that limit the type and form of amendments. Once debate has concluded and all amendments have been voted on, the House votes on the bill. If it passes, the bill is sent to the Senate.

When an appropriations bill goes onto the Senate floor, it also goes through a period of debate and amendment. The Senate has its own specific rules for what kinds of amendments may be offered on appropriations bills which are similar, but not identical, to the House rules. Individual senators may offer amendments to be voted on during this process. Once debate is complete, the Senate votes on the bill.

Once each chamber has passed a spending bill, the next step is a “conference” between the two chambers to iron out any differences between the two bills. This is generally done through a “conference committee” made up of members of the House and Senate. The conference committee then sends the conference bill to the House and Senate for vote. If either chamber rejects the conference bill, it is sent back to the conference committee. The conference committee also produces its own “joint explanatory statement” that may supplement or override the committee reports produced by the House and Senate.

Once the final version of the conference bill has been agreed upon, it is brought to a vote in the House and Senate. If both houses pass the bill, it goes to the president’s desk to be signed into law.

What Role Does the Public Play in the Government Funding Process?

The general public has a number of opportunities to weigh in before a bill is eventually passed. These opportunities can be broadly divided into three major periods:

- Before the House and Senate consider each respective chamber’s bill.

- When the bill is being considered in committee.

- After the bill has passed through the House and the Senate.

During each of these periods, different forms of advocacy may be helpful in effecting change in the bill.

Advocacy before a bill is formally considered.

Advocacy during this stage of the appropriations process can occur in many different ways. Some people may wish to approach the OMB or individual government agencies before the president’s budget is released in February, in order to provide suggestions and input. Many agencies provide robust stakeholder meeting opportunities throughout the year that allow advocates and other members of the public to weigh in on the agency’s operations. Because the president’s budget sets the overall tone for Congress, the president’s inclusion or exclusion of specific line items, or proposals to reduce or increase an agency’s budget, can be highly influential to Congress.

Advocacy with congressional appropriators is also a way for the public to influence the government funding process. Meeting with members of congress who are on the Appropriations Committees, or with committee staff, can help appropriators understand complicated issues and learn about new ideas, either before a bill is formally introduced or while it is under consideration. For example, advocates supporting immigrants have called for the inclusion of language in government funding bills which would provide lawyers for immigrants facing deportation who cannot afford to hire counsel.

Finally, advocacy with individual legislators is also important prior to the introduction of a government funding bill. During the early stages of the appropriations process, committees provide members of Congress with a broad opportunity to request specific line items to be included in the bill. These requests are not binding and the committees do not necessarily accept them, but they are the primary means by which members of Congress who are not on Appropriations Committees can influence government funding. This process usually occurs within the first two months after the president’s budget is published.

As part of this process, many members of Congress have created specific procedures for members of the public to submit requests for the inclusion of specific items in government funding bills. A Congressional office may have its own independent mechanism for taking these submissions, such as submission of comments on its official website or the use of Google Forms. These opportunities usually end by the spring.

Advocacy occurring before a bill has been produced and submitted to a vote by an Appropriations Committee or subcommittee is often the most impactful. In the world of immigration, advocacy with the Homeland Security Subcommittee; the Commerce, Justice, Science and Related Agencies Subcommittee; the Labor, Health and Human Services, Education, and Related Agencies Subcommittee; and the State, Foreign Operations, and Related Programs Subcommittee are most likely to produce results.

Advocacy while a bill is being considered in committee.

Once the House and Senate have produced a bill, usually in the summer or fall, advocates may lobby for the inclusion of specific amendments which modify the text of the bill. The majority of such amendments are offered when a bill is being considered in the relevant subcommittee, so advocates generally focus their efforts on members of Congress who serve on that subcommittee. Advocates may also push for Congress to reject the bill entirely.

Advocacy after a bill is passed through the House and Senate.

Once both the House and the Senate have passed their government funding bills, those bills will often go through a “conference” process to resolve differences between them. Because conference negotiations require both houses of Congress to come to a compromise, advocates may lobby individual members of the relevant conference committee or committee staff to include or exclude specific provisions that are in one bill but not the other, or to modify the text of the bill to address concerns that were raised after the bills were first passed. However, the conference process is unlikely to produce results that are significantly different than what passed the House and Senate originally.

The Impact of Government Funding Bills on Immigration

Although the legal immigration system is largely supported by fees on applications and petitions, and not funding passed by Congress in appropriations bills, other parts of the immigration system—immigration enforcement in particular—are impacted significantly by funding bills. For example, the base level of funding for ICE’s “Custody Operations” budget theoretically determines how many immigrants can be held in detention centers each year. However, in practice ICE often detains more immigrants than Congress has funded by pulling money from other parts of the DHS budget. Funding levels also determine if sections of a border wall can be built, or how many Border Patrol and ICE agents can be hired. As a result, advocates have often pushed Congress to lower the overall budget for immigration enforcement agencies, which has grown significantly over the last two decades.

Even though the legal immigration system is mostly fee-funded, Congress can also support the system in times of increased backlogs through the appropriations process. For example, in the FY 2022 budget, President Biden has requested $345 million to fund “backlog reduction” at USCIS.

Government funding bills have also proven to be a resource for establishing some safeguards on immigration enforcement. For example, in FY 2019, Congress included language preventing ICE from using information shared by the Office of Refugee Resettlement to target individuals who come forward to sponsor an unaccompanied child being held in a government shelter.

Congress has also used government funding bills to promote transparency in immigration processes. After members of Congress were barred from entering facilities holding migrant children in 2018, Congress included language requiring DHS to admit members of Congress into those facilities to conduct oversight. Other notable transparency provisions included in government funding bills include a requirement that ICE post detailed weekly data on immigrants held in ICE detention.