Noncitizens who are not legally present in the United States, and noncitizens who are legally present but who are accused of violating a requirement of their legal status, may find themselves facing deportation from the country. Many noncitizens are subject to deportation proceedings while behind bars and without having the benefit of legal counsel. Recently arrived undocumented immigrants in particular tend to be quickly deported or expelled from the United States by low-level Department of Homeland Security (DHS) officials without a judge ever being involved. However, some noncitizens do get the chance to make their case to avoid removal to an immigration judge. Individuals who find themselves in front of an immigration judge in immigration court face the possibility that the judge will order them deported, or “removed,” from the United States. But, in many cases, noncitizens can ask the judge to grant them some form of “relief from removal,” which will allow them to stay in the United States.

The Removal System

There are approximately 11 million people in the United States who do not have regular immigration status and are commonly referred to as “undocumented.” About 1.19 million of these individuals already have “final orders of removal,” but remain in the United States either through official executive discretion or because immigration officials do not know their location.

Recent arrivals usually are subject to rapid “summary removal” by low-level DHS officials. Under the “expedited removal” system created in 1996, most immigrants apprehended at the border within 14 days of entry into the United States can be ordered deported without a judge’s involvement, unless they express a fear of persecution in their home country or wish to seek asylum. Similarly, individuals who have previously been deported can be subject to rapid “reinstatement of removal” if they cross the border again. Beginning in March 2020, DHS also gained the authority to expel migrants without even issuing a deportation order under “Title 42,” a temporary public health authority exercised by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). However, any immigrant who expresses fear of return to their home country is supposed to receive a “credible fear interview” by an asylum officer.

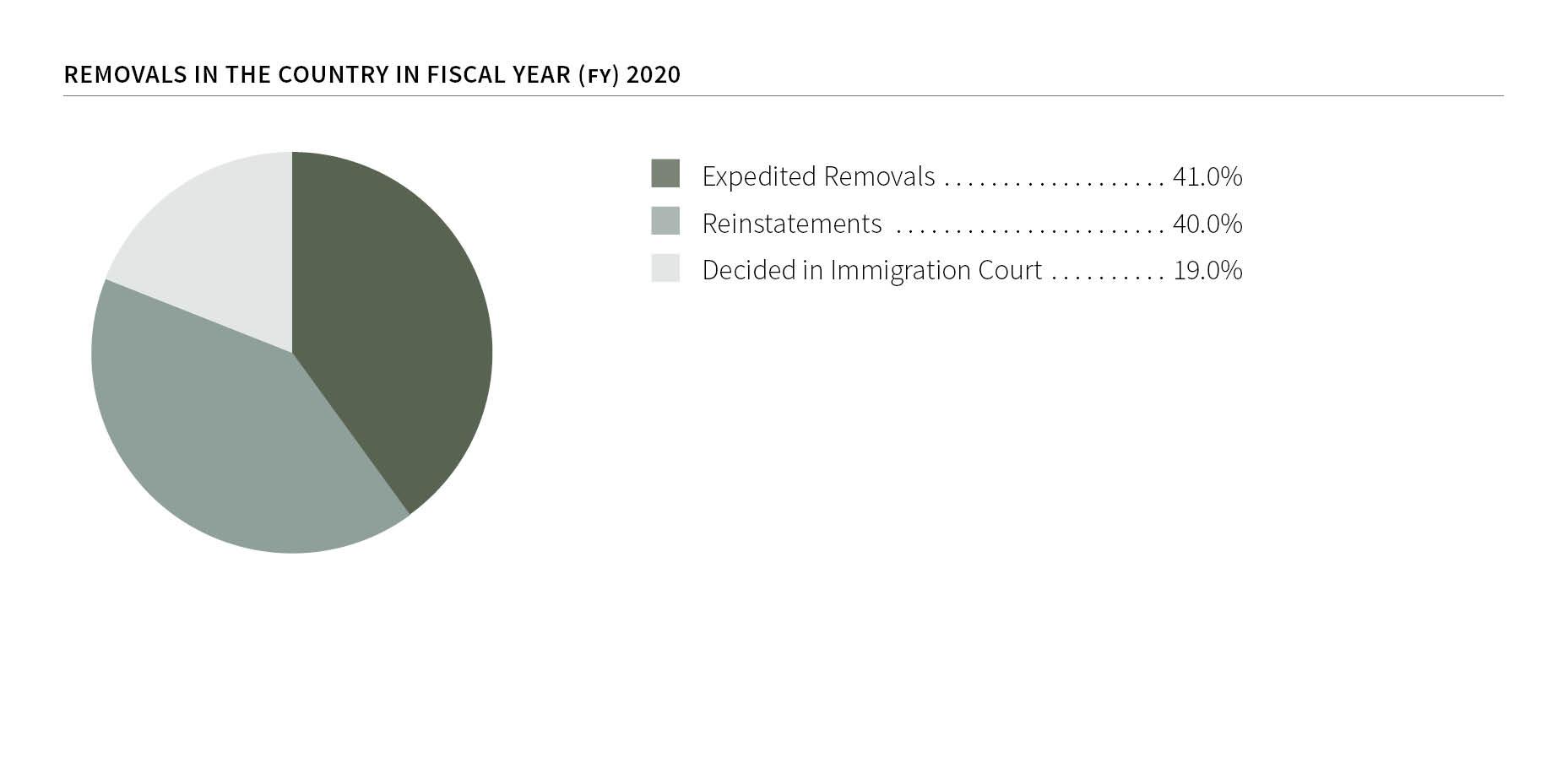

In Fiscal Year (FY) 2020, expedited removals accounted for 41 percent of all removals from the country and reinstatements accounted for another 40 percent. But for those remaining noncitizens not subjected to expedited removal or summarily expelled at the border, an immigration judge must determine whether each individual can be legally removed from the country under the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA). To initiate the immigration court process, DHS must first file a charging document—called a “Notice to Appear”—alleging the basis for removal. Then a DHS attorney must prosecute the case and the immigration judge must decide if the government has the legal authority to “remove” the noncitizen in question. A noncitizen who is found to be “removable” may be eligible to apply for some form of “relief from removal,” which the judge decides whether to grant.

In an immigration court “removal” case, the U.S. government bears the initial burden of establishing “alienage”—that is, determining whether the person is a noncitizen in the first place. This requirement is key because citizenship records are often incomplete and immigration officials occasionally attempt to deport U.S. citizens as a result.

Once the government has met its burden of proving that a person is not a U.S. citizen, the judge must determine if the government can legally remove that person. Noncitizens who are “applying for admission” into the United States (which can include people who have already been in the country for a long time but have no legal status) have the burden to prove that they are “clearly and beyond doubt” admissible. However, if a noncitizen is already considered to have been admitted into the country, it is the government which bears the burden to prove by “clear and convincing evidence” that this person is removable.

Individuals may be removable for a wide variety of reasons. For instance, they may be present in the country without lawful admission or parole, or they may have been admitted legally but failed to maintain their status. Noncitizens with lawful status may become removable for many reasons, such as immigration fraud, certain criminal convictions, national security, or false claims to U.S. citizenship.

If the immigration judge finds that a person is not removable, including cases where the government fails to meet its burden, then that case will be terminated—meaning the case is over. A termination can be “with prejudice,” which prohibits the government from bringing the exact same removal case again, or “without prejudice,” which allows the government to file a new “Notice to Appear” and make a second attempt at removal.

Noncitizens who are deemed “removable” may be eligible to apply for “relief from removal.” An immigration judge must decide on a case-by-case basis if a particular noncitizen qualifies for any form of relief from removal. Some forms of relief from removal include:

- Cancellation of Removal: A form of pardon that allows an immigration judge to “cancel” a finding of removability and permit a person to remain in the United States as a lawful permanent resident. There are two forms of cancellation of removal. One is available to certain lawful permanent residents who have been in the United States for at least 7 years and have subsequently become removable. The other is available only to undocumented immigrants who have been in the United States for at least 10 years, and who can prove that their deportation would cause “extreme and exceptionally unusual hardship” to a close relative who is a U.S. citizen or lawful permanent resident. A person may only be granted cancellation of removal a single time.

- Asylum: All noncitizens who are physically present in the United States have a right to apply for asylum. Asylum is granted to individuals who have a well-founded fear of persecution if returned to their home country. The recipient becomes eligible for a green card after one year.

- Withholding of Removal: For noncitizens who, though not qualified for asylum, still cannot be returned to a particular country because their life or freedom would be threatened due to their “race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group, or political opinion.”

- Convention Against Torture Protection: For noncitizens who can establish that they would probably be tortured if returned to their home country.

- Adjustment of Status: Applications for lawful permanent resident status (a green card), which are usually handled by U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS), must be decided by an immigration judge if the person who filed the application has been put into the removal process. Immigration judges can also determine whether to issue waivers for certain types of conduct that might be an obstacle to approving the application.

Some people seek forms of relief from removal that are adjudicated by USCIS, such as a request for a “U visa” for victims of serious crimes who cooperate with law enforcement. In some circumstances, an immigration judge may “administratively close” an immigration case, taking it off the docket and putting it into an indefinite limbo to allow a person to request a benefit from USCIS without having to simultaneously defend against removal.

Most forms of relief from removal also come with lawful status, such as lawful permanent residence or asylee status. However, some forms of relief, such as withholding of removal, only provide limited protections from removal and do not grant any permanent lawful status.

Some forms of relief from removal require the judge to hold a mini-trial, known as an “individual hearing.” At these hearings, the noncitizen and the government may present evidence to demonstrate to the judge whether the noncitizen is eligible for relief, and—if so—whether they should be granted relief. If an immigration judge finds that a noncitizen is removable, but grants relief from removal, then the person can remain in the United States. The government can appeal this decision to the Board of Immigration Appeals (BIA), then to a federal circuit court, and potentially all the way up to the Supreme Court.

If an immigration judge finds a noncitizen to be removable, denies relief from removal, and issues a removal order or grants voluntary departure at the end of the proceeding, the noncitizen still has the right to appeal. A removal order is only considered final if the 30-day period to file an appeal has run out, if the noncitizen waives the right to appeal, or if the BIA dismisses the appeal or affirms the removal order in some other way. Some noncitizens are deported while they are still in the process of appealing.

Once a noncitizen’s removal order has been issued, the government then must decide whether to execute the order. In some cases, Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) decides to grant a “stay of removal,” often for humanitarian reasons. In other cases, individuals are provided with “deferred action,” a form of executive clemency that allows people to temporarily remain in the United States and to work here.

If the government decides to execute a removal order, the person against whom the order was issued will be notified and ordered to surrender to ICE on a particular date to be taken into custody and deported. Anyone who fails to report for removal becomes a target for arrest by ICE.

Civil Removal Proceedings and Criminal Law

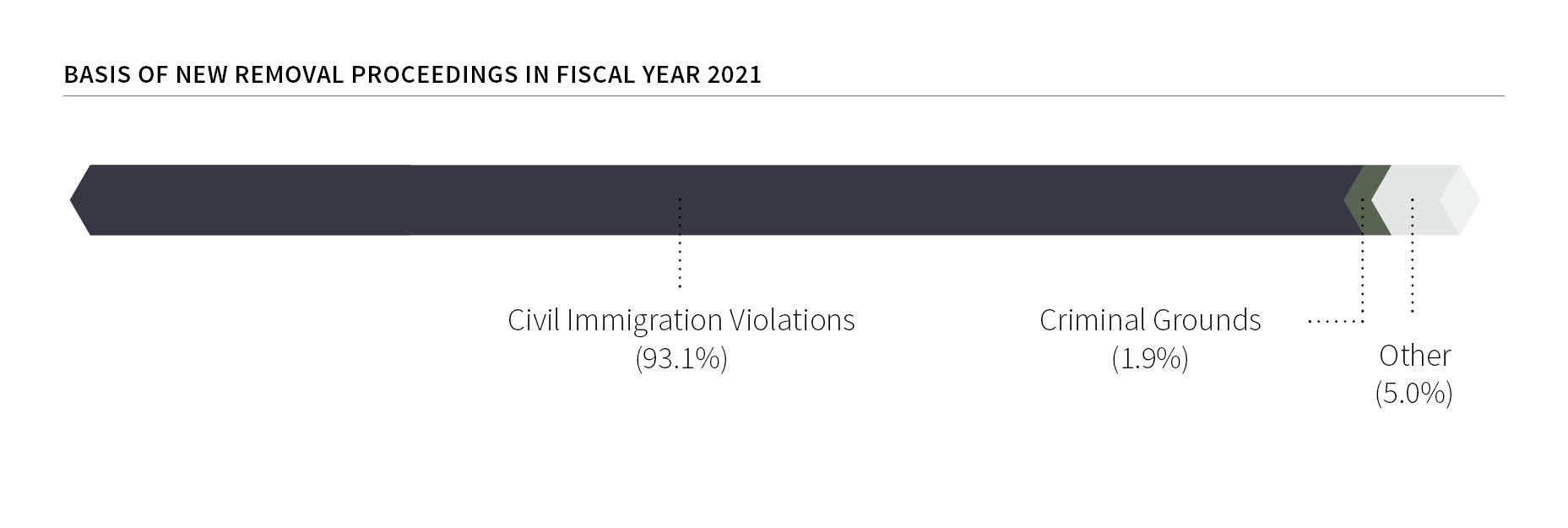

Civil removal proceedings are distinct from the criminal legal system. Although some criminal convictions can be grounds for removal, most people in removal proceedings are charged with civil infractions such as not having lawful immigration status. The Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse (TRAC) estimates that, in FY 2021, only 1.9 percent of new removal proceedings were based on criminal grounds, while 93.1 percent were based solely on civil immigration violations (mostly entry without inspection).

Some removal proceedings are initiated based on criminal convictions that are nonviolent or otherwise minor—but which are labeled “aggravated felonies” under immigration law. For instance, misdemeanor theft of a video game and selling $10 worth of marijuana are not truly “aggravated” or “felonies,” but they may still be defined that way in immigration court and are grounds for putting someone in removal proceedings. If a judge determines that a particular individual has a prior conviction for an “aggravated felony,” regardless of how serious or minor the conviction was, that person may be barred from many forms of relief from removal.

A noncitizen with a criminal conviction is entitled to a thorough hearing before an immigration judge to determine if that conviction has any immigration consequences. Federal immigration law is constantly evolving regarding whether a particular criminal offense makes someone removable from the country or precludes them from being granted immigration relief. Most noncitizens begin removal proceedings after the completion of any criminal sentence they have served. However, a small number begin removal proceedings while still serving their criminal sentence through the Institutional Hearing Program (IHP). And, in some rare cases, federal judges issue an order of removal as part of a criminal sentence.

The removal system and the criminal legal system also intersect through information-sharing programs. Under programs like Secure Communities, the fingerprints of everyone arrested by a state or local law-enforcement agency (LEA) are sent to ICE to be checked against immigration databases. If the fingerprints of a particular noncitizen match and ICE has probable cause to believe that noncitizen is deportable, ICE issues a “detainer” requesting that the LEA holding the person continue to hold them for up to 48 hours longer than they normally would, thereby allowing ICE sufficient time to take the person into custody. However, compliance with detainers is voluntary and many LEAs do not honor them. ICE does sometimes begin removal proceedings against someone in LEA custody by filing a “Notice to Appear.

Relief from Removal After a Removal Order is Issued

U.S. immigration law allows for administrative or judicial review of final orders of removal issued during removal proceedings. To begin with, the INA guarantees the right to file one “motion to reopen” immigration proceedings after a final order of removal is received. The motion can be filed either with the immigration judge or the BIA and allows a noncitizen to present the court with new facts in support of their case.

A motion to reopen must “state the new facts that will be proven at a hearing if

the motion is granted” and include “affidavits or other evidentiary material.” Some common grounds for reopening are as follows:

- conditions in a person’s “home” country have changed;

- the person who is the target of the removal order is a survivor of domestic abuse;

- the person’s prior counsel was ineffective and prejudiced the case;

- the person has convictions that were newly vacated;

- the person’s personal circumstances have changed their eligibility for relief;

- newly issued case law has changed the person’s removability or eligibility for relief.

Generally, the immigration judge or BIA must receive a motion to reopen within 90 days of the final removal order. However, that requirement can be waived if the case is judged to merit “equitable tolling”—the principle that “non-jurisdictional requirements” such as filing deadlines should be extended if the individual making the request missed the original deadline due to “extraordinary circumstances.”

There are specific circumstances in which there is no deadline for filing a motion to reopen. For instance, noncitizens who want to request asylum relief based on changed country conditions do not face a deadline to reopen. And noncitizens who were ordered removed “in absentia”—that is, after they did not show up for hearings—can have their cases reopened at any time if they demonstrate that they never received a hearing notice. Between 2008 and 2018, about 15 percent of people who were ordered removed in absentia successfully reopened their cases and had their removal orders rescinded.

Release from Immigration Detention

Once a noncitizen receives a final order of removal, ICE is generally directed to detain them and attempt to remove them during the 90 days after the removal order becomes final—which is known as the “removal period.” ICE retains the discretion to detain individuals longer than this if they have certain criminal convictions or if the government determines that they are “a risk to the community or unlikely to comply with the order of removal.” ICE can continue detaining these persons as long as the detention is subject to administrative post-order custody reviews.

The Supreme Court has held that six months is the longest, in general, that ICE can continue to detain someone in order to facilitate their removal from the country. After that point, if the noncitizen can show that there is “good reason to believe” that removal is not significantly likely in the reasonably foreseeable future, ICE is required to release the person unless the government can show that this person should be kept in detention. If ICE decides to release someone with a final order of removal for any of the reasons listed above, the agency must issue an Order of Supervision (OSUP). This is similar to probation or supervised release and specifies conditions the supervisee must observe, such as reporting regularly to ICE or wearing an electronic ankle monitor.

ICE also operates an Alternatives to Detention (ATD) program for individuals it has determined can be released from custody and who are still in ongoing removal proceedings. The ATD program offers different forms of supervision such as wearing a global positioning system (GPS) tracking device as an ankle bracelet, putting a smartphone application on one’s cell phone (SmartLINK), and accepting regular home or office visits from ICE personnel. The ATD program costs between $0.70 and $17 per day, compared to between $126 and $182 per day to detain someone in an adult detention facility.